LEGEND Your Song of the Day

- Thread starter Prime Time

- Start date

-

To unlock all of features of Rams On Demand please take a brief moment to register. Registering is not only quick and easy, it also allows you access to additional features such as live chat, private messaging, and a host of other apps exclusive to Rams On Demand.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #1,323

Rams and Gators

Legend

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #1,326

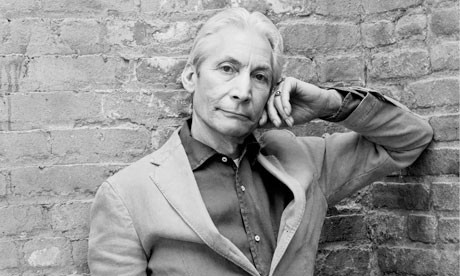

An interview from last year with drummer Charlie Watts follows.

Charlie Watts

by Caspar Llewellyn Smith

So Charlie, the Stones are playing Glastonbury! Excited?

I don't want to do it. Everyone else does. I don't like playing outdoors, and I certainly don't like festivals. I've always thought they're nothing to do with playing. Playing is what I'm doing at the weekend (1). That's how I was brought up. But that's me, personally. When you're a band … you do anything and everything. But Glastonbury, it's old hat really. I never liked the hippy thing to start with. It's not what I'd like to do for a weekend, I can tell you.

But surely …

[Interrupting] The worst thing playing outdoors is when the wind blows, if you're a drummer, because the cymbals move … it really is hard to play then.

Well, you're also playing Hyde Park this summer. What do you remember about your famous gig there in 1969 (2)?

Oh, quite a lot. The Dorchester! That was our dressing room. And Allen Klein walking about like Napoleon. He was the same kind of shape. And the armoured van going into the crowd. I had to rush around and get my silver trousers done for it. And then Mick Taylor, of course, it was his first big gig. And my wife got hit with a stale sandwich. I remember her going mad with that. I don't blame her. She got hit on the back. She reckoned it was stale because it obviously hurt a lot. The butterflies. I didn't like that, because the casualty rate was worse than the Somme. Half of them went woosh. And the other half of them were dead.

Were you still in shock from Brian [Jones]'s death?

Shock? Brian dying? No. It was very sad but it wasn't unexpected. We'd carried him for a few tours and he was quite ill. We were young, we didn't know what was wrong with him. I still don't really. He always suffered from terrible asthma, and he drank heavily on the road and he got into drugs before anyone else in the band. It was a question of, "Do we carry on?"

And Mick Taylor joined the band …

Amazing player. I think we did our best music with Mick.

Hyde Park was the height of the hippy thing …

Altamont was more hippy than that, I thought. That was a very peculiar one, that was.

With a lot of big stadium bands these days, it feels like the staging of the show is the most important thing, whereas the Stones still strike me as being a real band. Sometimes you're good and sometimes … less so.

Mick [Jagger] is the show, really. We back him. But Mick wouldn't dance well if the sound was bad. It doesn't come into it with a lot of bands because the lead singer just stands there. We've always been about playing it properly. I don't mean technically brilliant … The rest is candyfloss, it's froth. You know, the costumes you're wearing, that's … [shrugs] What you're really doing is playing the drums or the guitar.

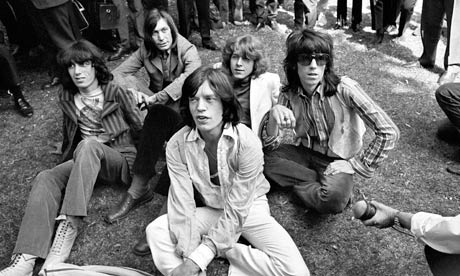

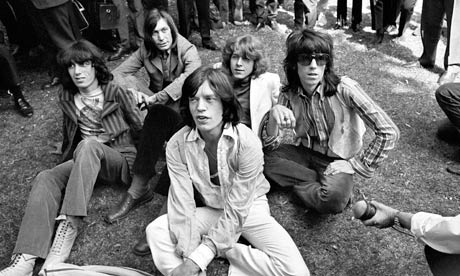

The Rolling Stones in 1969, before their concert in Hyde Park. Left to right: Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts, Mick Jagger, Mick Taylor and Keith Richards. Photograph: PA

The Rolling Stones in 1969, before their concert in Hyde Park. Left to right: Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts, Mick Jagger, Mick Taylor and Keith Richards. Photograph: PA

What do you think of drum machines?

They're great for songwriters and producers. Recording is a very precise thing – it's playing it dead right every time, and it can be fun. But if you're writing a song, it's great to be able to tell the machine you'd like it louder, rather than having to tell the drummer. It's not what I'm interested in. I like the drum kit sound and somebody playing it – preferably me, but it could be anyone.

Given your jazz background, was it a bit of a comedown when you joined the Stones?

It was more of a shock joining Alexis Korner (3). I'd never played with a harmonica player before – I couldn't believe Cyril Davies when he started playing! We only played out of London once, in Birmingham. Cyril got £1 because he was a professional musician; so did [sax player] Dick Heckstall-Smith and [bassist] Jack Bruce. I wasn't so I got half a crown. Fantastic, isn't it? Half a crown! The Stones were just another gig, but then we started touring around England … I was waiting to start another job, but I never went back to it. I was a bit out of sync with all of them, Brian, Mick and Keith [Richards], but Keith taught me to listen to Buddy Holly and things like that. Mick taught me a lot about playing with songs, really, the melodies and that.

Was part of the Stones' success down to the fact that each of you had really done your homework?

I sort of agree with that. Everything's easier and quicker now. I wanted to be Max Roach or Kenny Clarke playing in New York with Charlie Parker in the front line. Not a bad aspiration. It actually meant a lot of bloody playing, a lot of work. I don't think kids are interested in that. But that may be true of every generation, I don't know. When I was what you'd call a young musician, jazz was very fashionable. It was very hip to know there was a new Miles Davis album out. Now no one knows what records come out. Especially me! Because of this thing [gestures at my iPhone recording the interview, with the inference that it is somehow the devil's work] … But in those days … an album: you kept it, you treasured it.

You must have really studied the records you had.

Oh, we did. I remember a Duke Ellington album that we played for ever.

And you must have had to save up for them.

I'd swap things: a cymbal for a certain record … Then I'd go to Ray's Jazz Shop (4). That's when it was in New Oxford Street, in the basement of Collet's. God bless him! He was green, he was never allowed to see daylight, they used to keep him in the cellar. And then I'd sell the record and go and buy the cymbal back.

What was your big problem with the hippies when that all started?

I wasn't a great one for the philosophy and I thought the clothes were horrendous, even then.

So what did you think of the rest of the Stones in their Satanic Majesties phase?

I didn't mind them doing it. Brian was the first one at it. I remember him doing the London Palladium with his bloody hat on, and his pipe and sitar … fantastic. Brian was the first one to know and meet as a friend Bob Dylan, and Jimi Hendrix. He used to be fun in those days.

At the height of the Stones' success in the 60s, did you have a sense that you were making history?

No. It was just a case of keeping up with everyone else. It's still the same now.

You said the band did its best work with Mick Taylor. What's your favourite Stones song?

God, I don't really have one to be honest, I don't really listen to them that much.

Do you think Bill [Wyman] made a mistake in leaving the group?

No, not a mistake, because he was in the middle of a terrible marriage that he should never have got into – he had a horrendous time with the Mandy girl – and he then married a very good woman and had three children very quickly … and he was very, very happy. But it was a shame he left because a) it was great having him and b) I think he missed out on a very lucrative period in our existence. There were very sparse periods you went through building the band, and he didn't really reap the rewards that we do now.

What do you spend your money on?

Me? I collect things.

Old records?

Yeah. There's a great place in Vienna. I collect jazz mostly. Drum kits as well. I've got one of Kenny Clarke's drum kits that he gave to Max Roach – I bought it off his widow. I have Duke Ellington's, the famous Sonny Greer drum kit, it's fantastic. Big Sid Catlett, one of the great 30s swing drummers, one of his … [continues in this vein for some time]. And books. Not antiquarian books. Signed first editions of mostly 20th-century writers. Agatha Christie: I've got every book she wrote in paperback. Graham Greene, I have all of them. Evelyn Waugh, he's another one. Wodehouse: everything he wrote.

It sounds like quite a healthy addiction.

Well, I'm old. It's not the sort of thing a boy of 20 would be keen on.

Have there been times when you've thought about knocking it on the head?

I thought that before the O2, but it was actually very comfortable to do. It was good fun, is what I meant to say.

But you had misgivings.

Misgivings? Yeah, oh yeah, I always do. It's a young person's [game]. The thing I find difficult is that 50% of it is image, not my side of it, but it is, and as you get a bit older you think, "Oh gawd!" I don't like looking at the pictures. I think Bowie looks all right. For some reason everyone's talking about David Bowie at the moment. But he does look good. Some others haven't weathered so well. And some guys who were really on fire haven't made it. It can take its toll on you. Without you knowing, or caring at the time, because you don't care when you're in your 30s or 40s.

Was it fun playing with Mick[Taylor] and Bill again at the O2 show?

It was great. I loved it.

And what about your guests, there and in the States?

It was really good. We were lucky we had Jeff Beck. He's a phenomenal player.

What about the younger bunch like Florence and the Machine?

Florence, she was all right. Lady Gaga was a really good sport. But they hung about with my granddaughter more than they did with me. We're silly old farts! I think Mick tries to keep up with them …

As well as Hyde Park, you've also announced a US tour.

It's a very short tour for us. It's only 18 shows. It's nothing.

Who's the driving force in putting the band back on the road?

Well, you wouldn't do it if Mick didn't want to do it. You've got to have Mick and Keith, but the driving force is Mick. If he's enthusiastic, he'll push everyone along. Keith's much more laidback about it.

Are they getting on well? Keith was quite rude about Mick in his book.

Oh yeah. Oh, that. Brothers, innit? Brothers in arms. You just let it take its course, really, things like that.

Is there any more new music in the offing?

There's nothing yet. I've lost track with the record industry world, I don't get it any more. It's gone beyond me. The last single I thought was very good, but things don't mean anything any more. They're just tacked on the end of a reissue – and that ends up selling more than a new album. It's not like when Sgt Pepper came out and you thought, "Blimey! We'd better do one better …" People say you need a new album out when you go on tour. Well, we did that on our last tour, and I don't know if the record sold. I suppose, as Mick says, it gives us something different to play on stage. It's not Brown Sugar again.

Does it ever feel like you're just going through the motions on stage?

Sometimes you're pot-boiling. Sometimes you're on song.

So will you get to a point where you say, "That's it, no more"?

You do now seriously have to look at your age, because if this goes on for another two years, I'll be 73. But I say that at the end of every tour. And then you have two weeks off and your wife says, "Aren't you going to work?"

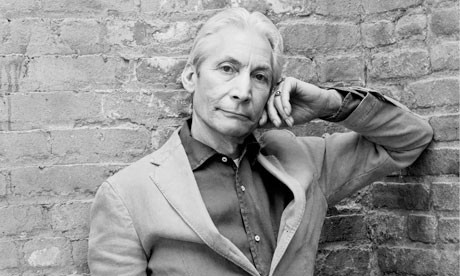

Charlie Watts

by Caspar Llewellyn Smith

So Charlie, the Stones are playing Glastonbury! Excited?

I don't want to do it. Everyone else does. I don't like playing outdoors, and I certainly don't like festivals. I've always thought they're nothing to do with playing. Playing is what I'm doing at the weekend (1). That's how I was brought up. But that's me, personally. When you're a band … you do anything and everything. But Glastonbury, it's old hat really. I never liked the hippy thing to start with. It's not what I'd like to do for a weekend, I can tell you.

But surely …

[Interrupting] The worst thing playing outdoors is when the wind blows, if you're a drummer, because the cymbals move … it really is hard to play then.

Well, you're also playing Hyde Park this summer. What do you remember about your famous gig there in 1969 (2)?

Oh, quite a lot. The Dorchester! That was our dressing room. And Allen Klein walking about like Napoleon. He was the same kind of shape. And the armoured van going into the crowd. I had to rush around and get my silver trousers done for it. And then Mick Taylor, of course, it was his first big gig. And my wife got hit with a stale sandwich. I remember her going mad with that. I don't blame her. She got hit on the back. She reckoned it was stale because it obviously hurt a lot. The butterflies. I didn't like that, because the casualty rate was worse than the Somme. Half of them went woosh. And the other half of them were dead.

Were you still in shock from Brian [Jones]'s death?

Shock? Brian dying? No. It was very sad but it wasn't unexpected. We'd carried him for a few tours and he was quite ill. We were young, we didn't know what was wrong with him. I still don't really. He always suffered from terrible asthma, and he drank heavily on the road and he got into drugs before anyone else in the band. It was a question of, "Do we carry on?"

And Mick Taylor joined the band …

Amazing player. I think we did our best music with Mick.

Hyde Park was the height of the hippy thing …

Altamont was more hippy than that, I thought. That was a very peculiar one, that was.

With a lot of big stadium bands these days, it feels like the staging of the show is the most important thing, whereas the Stones still strike me as being a real band. Sometimes you're good and sometimes … less so.

Mick [Jagger] is the show, really. We back him. But Mick wouldn't dance well if the sound was bad. It doesn't come into it with a lot of bands because the lead singer just stands there. We've always been about playing it properly. I don't mean technically brilliant … The rest is candyfloss, it's froth. You know, the costumes you're wearing, that's … [shrugs] What you're really doing is playing the drums or the guitar.

What do you think of drum machines?

They're great for songwriters and producers. Recording is a very precise thing – it's playing it dead right every time, and it can be fun. But if you're writing a song, it's great to be able to tell the machine you'd like it louder, rather than having to tell the drummer. It's not what I'm interested in. I like the drum kit sound and somebody playing it – preferably me, but it could be anyone.

Given your jazz background, was it a bit of a comedown when you joined the Stones?

It was more of a shock joining Alexis Korner (3). I'd never played with a harmonica player before – I couldn't believe Cyril Davies when he started playing! We only played out of London once, in Birmingham. Cyril got £1 because he was a professional musician; so did [sax player] Dick Heckstall-Smith and [bassist] Jack Bruce. I wasn't so I got half a crown. Fantastic, isn't it? Half a crown! The Stones were just another gig, but then we started touring around England … I was waiting to start another job, but I never went back to it. I was a bit out of sync with all of them, Brian, Mick and Keith [Richards], but Keith taught me to listen to Buddy Holly and things like that. Mick taught me a lot about playing with songs, really, the melodies and that.

Was part of the Stones' success down to the fact that each of you had really done your homework?

I sort of agree with that. Everything's easier and quicker now. I wanted to be Max Roach or Kenny Clarke playing in New York with Charlie Parker in the front line. Not a bad aspiration. It actually meant a lot of bloody playing, a lot of work. I don't think kids are interested in that. But that may be true of every generation, I don't know. When I was what you'd call a young musician, jazz was very fashionable. It was very hip to know there was a new Miles Davis album out. Now no one knows what records come out. Especially me! Because of this thing [gestures at my iPhone recording the interview, with the inference that it is somehow the devil's work] … But in those days … an album: you kept it, you treasured it.

You must have really studied the records you had.

Oh, we did. I remember a Duke Ellington album that we played for ever.

And you must have had to save up for them.

I'd swap things: a cymbal for a certain record … Then I'd go to Ray's Jazz Shop (4). That's when it was in New Oxford Street, in the basement of Collet's. God bless him! He was green, he was never allowed to see daylight, they used to keep him in the cellar. And then I'd sell the record and go and buy the cymbal back.

What was your big problem with the hippies when that all started?

I wasn't a great one for the philosophy and I thought the clothes were horrendous, even then.

So what did you think of the rest of the Stones in their Satanic Majesties phase?

I didn't mind them doing it. Brian was the first one at it. I remember him doing the London Palladium with his bloody hat on, and his pipe and sitar … fantastic. Brian was the first one to know and meet as a friend Bob Dylan, and Jimi Hendrix. He used to be fun in those days.

At the height of the Stones' success in the 60s, did you have a sense that you were making history?

No. It was just a case of keeping up with everyone else. It's still the same now.

You said the band did its best work with Mick Taylor. What's your favourite Stones song?

God, I don't really have one to be honest, I don't really listen to them that much.

Do you think Bill [Wyman] made a mistake in leaving the group?

No, not a mistake, because he was in the middle of a terrible marriage that he should never have got into – he had a horrendous time with the Mandy girl – and he then married a very good woman and had three children very quickly … and he was very, very happy. But it was a shame he left because a) it was great having him and b) I think he missed out on a very lucrative period in our existence. There were very sparse periods you went through building the band, and he didn't really reap the rewards that we do now.

What do you spend your money on?

Me? I collect things.

Old records?

Yeah. There's a great place in Vienna. I collect jazz mostly. Drum kits as well. I've got one of Kenny Clarke's drum kits that he gave to Max Roach – I bought it off his widow. I have Duke Ellington's, the famous Sonny Greer drum kit, it's fantastic. Big Sid Catlett, one of the great 30s swing drummers, one of his … [continues in this vein for some time]. And books. Not antiquarian books. Signed first editions of mostly 20th-century writers. Agatha Christie: I've got every book she wrote in paperback. Graham Greene, I have all of them. Evelyn Waugh, he's another one. Wodehouse: everything he wrote.

It sounds like quite a healthy addiction.

Well, I'm old. It's not the sort of thing a boy of 20 would be keen on.

Have there been times when you've thought about knocking it on the head?

I thought that before the O2, but it was actually very comfortable to do. It was good fun, is what I meant to say.

But you had misgivings.

Misgivings? Yeah, oh yeah, I always do. It's a young person's [game]. The thing I find difficult is that 50% of it is image, not my side of it, but it is, and as you get a bit older you think, "Oh gawd!" I don't like looking at the pictures. I think Bowie looks all right. For some reason everyone's talking about David Bowie at the moment. But he does look good. Some others haven't weathered so well. And some guys who were really on fire haven't made it. It can take its toll on you. Without you knowing, or caring at the time, because you don't care when you're in your 30s or 40s.

Was it fun playing with Mick[Taylor] and Bill again at the O2 show?

It was great. I loved it.

And what about your guests, there and in the States?

It was really good. We were lucky we had Jeff Beck. He's a phenomenal player.

What about the younger bunch like Florence and the Machine?

Florence, she was all right. Lady Gaga was a really good sport. But they hung about with my granddaughter more than they did with me. We're silly old farts! I think Mick tries to keep up with them …

As well as Hyde Park, you've also announced a US tour.

It's a very short tour for us. It's only 18 shows. It's nothing.

Who's the driving force in putting the band back on the road?

Well, you wouldn't do it if Mick didn't want to do it. You've got to have Mick and Keith, but the driving force is Mick. If he's enthusiastic, he'll push everyone along. Keith's much more laidback about it.

Are they getting on well? Keith was quite rude about Mick in his book.

Oh yeah. Oh, that. Brothers, innit? Brothers in arms. You just let it take its course, really, things like that.

Is there any more new music in the offing?

There's nothing yet. I've lost track with the record industry world, I don't get it any more. It's gone beyond me. The last single I thought was very good, but things don't mean anything any more. They're just tacked on the end of a reissue – and that ends up selling more than a new album. It's not like when Sgt Pepper came out and you thought, "Blimey! We'd better do one better …" People say you need a new album out when you go on tour. Well, we did that on our last tour, and I don't know if the record sold. I suppose, as Mick says, it gives us something different to play on stage. It's not Brown Sugar again.

Does it ever feel like you're just going through the motions on stage?

Sometimes you're pot-boiling. Sometimes you're on song.

So will you get to a point where you say, "That's it, no more"?

You do now seriously have to look at your age, because if this goes on for another two years, I'll be 73. But I say that at the end of every tour. And then you have two weeks off and your wife says, "Aren't you going to work?"

Some classic Sevendust to get pumped up for the game!

How these guys go twenty different directions and come back together on cue and doing it live has always blown me away

My first concert back in 1983. My older cousin took me.

Amazing.

It makes sense. Two different bands.Hope it works out for you. It's not supposed to be fun. That's why they pay you and call it work.Hope this cheers you up.

The 20 Greatest Songs About Work

A masterpiece by my favorite guitarist ever - Jeff Beck.

Totally agree. I never cared for them after the inclusion of Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks. I'm probably in the minority though.

Many prefer the old blues band.

I like them both. I just don't compare the two.

PhxRam

Guest

PhxRam

Guest

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #1,334

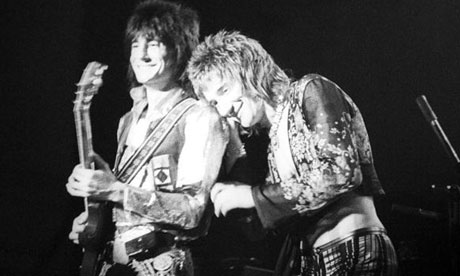

Personally I think that Rod Stewart's best work was done while with the Faces. This tune is followed by an interview done some time last year.

Rod Stewart: 'I thought songwriting had left me'

As the singer prepares to release his new album Time – the first he has written for in 15 years – he talks frankly about women, drugs – and his lifelong struggle with his craft

Rod Stewart: 'I’ll take any stick the press can throw at me.' Photograph: Penny Lancaster

We are talking about soul music. Rod Stewart is telling me what a disaster his 2009 covers album Soulbook was. "It was a DNA rifle-up," he says, his raspy voice made raspier still by a developing cold, "simply because you can't beat the originals. You'll never beat the originals, because they're still on the airwaves."

He didn't hear Cliff Richard's soul abum from 2011, then?

Stewart looks a little astonished. "He didn't do a soul abum …"

He did. Revue-style live show, too, with Percy Sledge and Freda Payne and James Ingram up on stage with him.

Stewart looks even more astonished. "Really?"

Yup. He looked a bit out of his depth, to be honest.

"Oh, bless him."

At 68, hair still spiky and sandy, skin the colour of antique furniture, Stewart remains a musician, then. If he is better known for countless things that have nothing to do with music – a list of statueseque, blonde partners (including three wives) longer than that of Cyprus's creditors; a selection of myths and legends ranging from him having been an apprentice professional footballer, to his stomach having been pumped clean of semen after he performed fellatio on a bar's worth of sailors in San Diego, to his having invented a way of taking cocaine anally – then it should be remembered that no one would know any of those stories if the music hadn't captured the public imagination in the first place.

The couple of albums he made with the Jeff Beck Group in the late 60s laid down the template that was then developed and coloured by Led Zeppelin. The solo albums he made for Mercury in the early 70s were perfect fusions of his musical loves – soul, folk, rock'n'roll – and the second side of his 1971 album Every Picture Tells a Story is as perfect a 20 minutes as rock has produced. The Faces, the group that ran concurrently with those albums – and with whom he would be delighted to reunite next year after everyone's schedules are clear, developed a reputation, through the booze fumes, as the surest guarantee of a good time that live music had to offer.

The problem for many listeners lies in the 40 or so years since. Which is an awfully long time, even if they have been punctuated with the occasional gem. Never mind that Every Picture and its attendant single Maggie May both topped the US and UK charts simultaneously – Stewart never seemed afraid to lower his standards in search of hits. And so we got the critic Greil Marcus's famous assessment: "Rarely has a singer had as full and unique a talent as Rod Stewart; rarely has anyone betrayed his talent so completely.

Once the most compassionate presence in music, he has become a bilious self-parody – and sells more records than ever." And that was written 33 years ago. Chances are, Marcus hasn't changed his mind since, especially since Stewart's Great American Songbook series of albums became the most commercially successful of his career.

But you know what? He gets a free pass, because most singers don't even manage his few years of near perfection – even if he doesn't seem too fussed about his art. It's perhaps telling that he seems more interested in talking about football, north-London property prices and our respective children than he is about Time, his new album – and the first on which he has contributed songwriting since 1998's When We Were the New Boys, a misfiring effort that also featured him coveringOasis and Primal Scream.

He is known less as a writer, though, than as an interpreter of other people's songs, and at his absolute best he deserves to be treated as rock's Sinatra – a superlative interpreter of superlative songs. He gets lots of Identikit Rod submissions, all swirling bagpipes and roaming in the gloaming, but he ignores them. But when he hears the right song, he looks for the way to make it a Rod Stewart song. "For instance, I'm sure Tom Waits wouldn't mind me saying this – Tom's Downtown Train, I realised there was a melody there in the chorus, and it's beautiful, but he barely gets up and barely gets down to the lower notes, so I took it to the extreme. That was a case where I brought the chorus alive and there have been a couple like that."

He says he's a better singer now than in his youth, despite his voice having lowered half a tone after his throat cancer in 2000. "I've got much better pitch, much better control, much better understanding of a song. I've always been able to get inside a song really easily, and if it's my song I can make it seem honest."

What happened to his writing? Why did he stop? "Ayeayeayeayeaye. A combination of the Great American Songbook albums, being somewhat lazy, and certain remarks made by a high-flying executive at a record company saying that my songs were shit and didn't sound like nothing new. Songwriting's never been a natural art for me; it's always been a bit of a struggle. I just thought it had got up and left me. I'd done the best I could and maybe I'd got nothing to write about any more."

He puts writing lyrics off until the last minute, "when the song's got a hook. The way I do it is hum and hah along while the band are playing. I sing whatever comes into my head and nine times out of 10 that will be the title of the song. Either that or I'd just write down a good title – likeYoung Turks or Baby Jane – and wait until the right vehicle comes along for it."

Stewart (right) with Ronnie Wood and the Faces performing live in 1972. Photograph: Ian Dickson/Redferns

But some of the lyrics on those Faces and early solo albums are wonderful – a unique combination of picaresque tales, music hall bawdiness and reminscence. "You really think so? Bless you. I always thought they were … Well, they're just black and white. I tell stories. I can't do that wonderful thing that Tom Waits and Bob Dylan do – to do imagery. I'm not good at that. I just write from the heart."

He only started writing again because his friend Jim Cregan forced him into it on a visit to Stewart's Essex mansion (he splits his time between there and LA). "He comes round for Sunday dinner when I'm in the country and always brings his guitar. I watch him come up the drive and … 'Oh, fucking hell, he's brought his guitar again.' He's always pushing me to write a song. So he says: 'Come on, siddown, let's have a go.' I said: 'No, I wanna have a little lie down. Just had Sunday dinner.' So he said: 'Come on, have a little go.' So I started singing, and he took it home, worked on the track a little bit, added a couple more guitars, and that was Brighton Beach."

That's one of the semi-autobiographical songs on the album, reflecting on his weekend beatnik days, hanging out under the pier with his girlfriend and his acoustic guitar in the early 60s; it's complemented by songs about his kids, his dad, his divorce. It's all very pleasant, though those who love Every Picture are unlikely to be putting it on constant rotation, despite the acoustic guitars and mandolins and fiddles being a presence again.

The critics, the sneerers, perhaps despair of Stewart because he has never been remotely apologetic about his success and its trappings: he's always happy to show off his latest car, blonde, house. "I've always put myself out there for ridicule," he says. "And the rewards are just wonderful, so I'll take any stick the press can throw at me."

Among the rewards were the string of women Stewart couldn't keep his hands off. Large chunks of his autobiography, published last year, are devoted to his efforts to keep his various girlfriends separate from one another, or from the press, before he chose fidelity in 1990 with his second wife, Rachel Hunter (they parted in 1999, divorcing in 2006). "There was a lot of smoke and mirrors in those days," he agrees. "It was like a Brian Rix comedy. One door slams, someone runs out in their brassiere, another door slams and someone comes out with their trousers round their ankles. It was very much like that."

Stewart with his third wife, Penny Lancaster-Stewart. Photograph: Stuart Wilson/Getty Images

Did he never think: Is this really worth the effort? "Nah," he says, sounding rather wistful, despite his evidently devoted marriage to wife No 3, Penny Lancaster-Stewart. "It was lovely. The only time it was getting sad was probably late 80s, when we had this 'Long Hot Summer' – me and one of my best mates were down in the south of France [he was making a video with Tina Turner]. And the girls were just coming in and out, from all over Europe. It was wonderfully easy, but there was a sadness about it, a shallow emptiness. Once you'd got your leg over, that was it."

Ah, the Long Hot Summer. In the book, he describes sleeping with a roll call of women.

"Let me say it was a minimum of three. It wasn't like one every night, coming in and going. It wasn't that bad! Jesus Christ! Three would be the number. Probably a maximum of four.

"I dunno how I got away with it. I was never ever a good-looking guy, but I knew I had a certain amount of charm, and most importantly I was the singer in a rock group. And I had a couple of bob. That's what turned the key in the door for me."

Did it make it harder to find The Right Woman when the choices open to him were so wide? Because he – in his prime, at least – could probably pull more women even than me. Probably.

He looks shocked.

"Than you?"

Than me.

There's silence for a couple of beats, then a rattle of outrageous laughter. "I thought you were serious. I'm a ROCK SINGER! It's dead easy. That was always my downfall. There's always someone prettier or better looking. Maybe I believed something magical was going to happen. And it did eventually."

The women aren't a myth. Some of the other things are. Stewart was never a grave-digger ("I just measured up the graves") nor an apprentice footballer ("I didn't even get close. I was good but I wasn't good enough"). He made those stories up to make himself more interesting in interviews. And he claims a publicist made up the one about the sailors and the stomach pump. "He had an evil streak in him. But you won't find, so far as I know, any written material on that anywhere. It was purely done through the grapevine. And I think the same thing happened to Richard Gere with a small rodent."

But the anal ingestion of cocaine is true. After his Faces bandmate Ronnie Wood discovered a hole in his septum, the pair decided to eschew the nasal route – which also helped Stewart protect his voice ("It dries all the membranes out. What it does to your nose, it does to your throat as well, cos it'll all go down the back of your throat as well") – and pack their coke into emptied aspirin capsules to take in suppository form. There was a problem, though: "It didn't have the same thrill as putting it up your nose, you know?"

And presumably it removes some of the social element from the ritual of taking drugs.

"No, you can't go in the toilet with the lads and lay one out." He hoots with laughter.

We part, and I mention I'd been playing my kids his old albums in the car.

"Did they like them?"

Sorry, no. But you know the maxim: Spare the Rod, spoil the child.

"Spare the Rod, spoil the child," he laughs delightedly. "Exactly!"

Rod Stewart: 'I thought songwriting had left me'

As the singer prepares to release his new album Time – the first he has written for in 15 years – he talks frankly about women, drugs – and his lifelong struggle with his craft

Rod Stewart: 'I’ll take any stick the press can throw at me.' Photograph: Penny Lancaster

We are talking about soul music. Rod Stewart is telling me what a disaster his 2009 covers album Soulbook was. "It was a DNA rifle-up," he says, his raspy voice made raspier still by a developing cold, "simply because you can't beat the originals. You'll never beat the originals, because they're still on the airwaves."

He didn't hear Cliff Richard's soul abum from 2011, then?

Stewart looks a little astonished. "He didn't do a soul abum …"

He did. Revue-style live show, too, with Percy Sledge and Freda Payne and James Ingram up on stage with him.

Stewart looks even more astonished. "Really?"

Yup. He looked a bit out of his depth, to be honest.

"Oh, bless him."

At 68, hair still spiky and sandy, skin the colour of antique furniture, Stewart remains a musician, then. If he is better known for countless things that have nothing to do with music – a list of statueseque, blonde partners (including three wives) longer than that of Cyprus's creditors; a selection of myths and legends ranging from him having been an apprentice professional footballer, to his stomach having been pumped clean of semen after he performed fellatio on a bar's worth of sailors in San Diego, to his having invented a way of taking cocaine anally – then it should be remembered that no one would know any of those stories if the music hadn't captured the public imagination in the first place.

The couple of albums he made with the Jeff Beck Group in the late 60s laid down the template that was then developed and coloured by Led Zeppelin. The solo albums he made for Mercury in the early 70s were perfect fusions of his musical loves – soul, folk, rock'n'roll – and the second side of his 1971 album Every Picture Tells a Story is as perfect a 20 minutes as rock has produced. The Faces, the group that ran concurrently with those albums – and with whom he would be delighted to reunite next year after everyone's schedules are clear, developed a reputation, through the booze fumes, as the surest guarantee of a good time that live music had to offer.

The problem for many listeners lies in the 40 or so years since. Which is an awfully long time, even if they have been punctuated with the occasional gem. Never mind that Every Picture and its attendant single Maggie May both topped the US and UK charts simultaneously – Stewart never seemed afraid to lower his standards in search of hits. And so we got the critic Greil Marcus's famous assessment: "Rarely has a singer had as full and unique a talent as Rod Stewart; rarely has anyone betrayed his talent so completely.

Once the most compassionate presence in music, he has become a bilious self-parody – and sells more records than ever." And that was written 33 years ago. Chances are, Marcus hasn't changed his mind since, especially since Stewart's Great American Songbook series of albums became the most commercially successful of his career.

But you know what? He gets a free pass, because most singers don't even manage his few years of near perfection – even if he doesn't seem too fussed about his art. It's perhaps telling that he seems more interested in talking about football, north-London property prices and our respective children than he is about Time, his new album – and the first on which he has contributed songwriting since 1998's When We Were the New Boys, a misfiring effort that also featured him coveringOasis and Primal Scream.

He is known less as a writer, though, than as an interpreter of other people's songs, and at his absolute best he deserves to be treated as rock's Sinatra – a superlative interpreter of superlative songs. He gets lots of Identikit Rod submissions, all swirling bagpipes and roaming in the gloaming, but he ignores them. But when he hears the right song, he looks for the way to make it a Rod Stewart song. "For instance, I'm sure Tom Waits wouldn't mind me saying this – Tom's Downtown Train, I realised there was a melody there in the chorus, and it's beautiful, but he barely gets up and barely gets down to the lower notes, so I took it to the extreme. That was a case where I brought the chorus alive and there have been a couple like that."

He says he's a better singer now than in his youth, despite his voice having lowered half a tone after his throat cancer in 2000. "I've got much better pitch, much better control, much better understanding of a song. I've always been able to get inside a song really easily, and if it's my song I can make it seem honest."

What happened to his writing? Why did he stop? "Ayeayeayeayeaye. A combination of the Great American Songbook albums, being somewhat lazy, and certain remarks made by a high-flying executive at a record company saying that my songs were shit and didn't sound like nothing new. Songwriting's never been a natural art for me; it's always been a bit of a struggle. I just thought it had got up and left me. I'd done the best I could and maybe I'd got nothing to write about any more."

He puts writing lyrics off until the last minute, "when the song's got a hook. The way I do it is hum and hah along while the band are playing. I sing whatever comes into my head and nine times out of 10 that will be the title of the song. Either that or I'd just write down a good title – likeYoung Turks or Baby Jane – and wait until the right vehicle comes along for it."

Stewart (right) with Ronnie Wood and the Faces performing live in 1972. Photograph: Ian Dickson/Redferns

But some of the lyrics on those Faces and early solo albums are wonderful – a unique combination of picaresque tales, music hall bawdiness and reminscence. "You really think so? Bless you. I always thought they were … Well, they're just black and white. I tell stories. I can't do that wonderful thing that Tom Waits and Bob Dylan do – to do imagery. I'm not good at that. I just write from the heart."

He only started writing again because his friend Jim Cregan forced him into it on a visit to Stewart's Essex mansion (he splits his time between there and LA). "He comes round for Sunday dinner when I'm in the country and always brings his guitar. I watch him come up the drive and … 'Oh, fucking hell, he's brought his guitar again.' He's always pushing me to write a song. So he says: 'Come on, siddown, let's have a go.' I said: 'No, I wanna have a little lie down. Just had Sunday dinner.' So he said: 'Come on, have a little go.' So I started singing, and he took it home, worked on the track a little bit, added a couple more guitars, and that was Brighton Beach."

That's one of the semi-autobiographical songs on the album, reflecting on his weekend beatnik days, hanging out under the pier with his girlfriend and his acoustic guitar in the early 60s; it's complemented by songs about his kids, his dad, his divorce. It's all very pleasant, though those who love Every Picture are unlikely to be putting it on constant rotation, despite the acoustic guitars and mandolins and fiddles being a presence again.

The critics, the sneerers, perhaps despair of Stewart because he has never been remotely apologetic about his success and its trappings: he's always happy to show off his latest car, blonde, house. "I've always put myself out there for ridicule," he says. "And the rewards are just wonderful, so I'll take any stick the press can throw at me."

Among the rewards were the string of women Stewart couldn't keep his hands off. Large chunks of his autobiography, published last year, are devoted to his efforts to keep his various girlfriends separate from one another, or from the press, before he chose fidelity in 1990 with his second wife, Rachel Hunter (they parted in 1999, divorcing in 2006). "There was a lot of smoke and mirrors in those days," he agrees. "It was like a Brian Rix comedy. One door slams, someone runs out in their brassiere, another door slams and someone comes out with their trousers round their ankles. It was very much like that."

Stewart with his third wife, Penny Lancaster-Stewart. Photograph: Stuart Wilson/Getty Images

Did he never think: Is this really worth the effort? "Nah," he says, sounding rather wistful, despite his evidently devoted marriage to wife No 3, Penny Lancaster-Stewart. "It was lovely. The only time it was getting sad was probably late 80s, when we had this 'Long Hot Summer' – me and one of my best mates were down in the south of France [he was making a video with Tina Turner]. And the girls were just coming in and out, from all over Europe. It was wonderfully easy, but there was a sadness about it, a shallow emptiness. Once you'd got your leg over, that was it."

Ah, the Long Hot Summer. In the book, he describes sleeping with a roll call of women.

"Let me say it was a minimum of three. It wasn't like one every night, coming in and going. It wasn't that bad! Jesus Christ! Three would be the number. Probably a maximum of four.

"I dunno how I got away with it. I was never ever a good-looking guy, but I knew I had a certain amount of charm, and most importantly I was the singer in a rock group. And I had a couple of bob. That's what turned the key in the door for me."

Did it make it harder to find The Right Woman when the choices open to him were so wide? Because he – in his prime, at least – could probably pull more women even than me. Probably.

He looks shocked.

"Than you?"

Than me.

There's silence for a couple of beats, then a rattle of outrageous laughter. "I thought you were serious. I'm a ROCK SINGER! It's dead easy. That was always my downfall. There's always someone prettier or better looking. Maybe I believed something magical was going to happen. And it did eventually."

The women aren't a myth. Some of the other things are. Stewart was never a grave-digger ("I just measured up the graves") nor an apprentice footballer ("I didn't even get close. I was good but I wasn't good enough"). He made those stories up to make himself more interesting in interviews. And he claims a publicist made up the one about the sailors and the stomach pump. "He had an evil streak in him. But you won't find, so far as I know, any written material on that anywhere. It was purely done through the grapevine. And I think the same thing happened to Richard Gere with a small rodent."

But the anal ingestion of cocaine is true. After his Faces bandmate Ronnie Wood discovered a hole in his septum, the pair decided to eschew the nasal route – which also helped Stewart protect his voice ("It dries all the membranes out. What it does to your nose, it does to your throat as well, cos it'll all go down the back of your throat as well") – and pack their coke into emptied aspirin capsules to take in suppository form. There was a problem, though: "It didn't have the same thrill as putting it up your nose, you know?"

And presumably it removes some of the social element from the ritual of taking drugs.

"No, you can't go in the toilet with the lads and lay one out." He hoots with laughter.

We part, and I mention I'd been playing my kids his old albums in the car.

"Did they like them?"

Sorry, no. But you know the maxim: Spare the Rod, spoil the child.

"Spare the Rod, spoil the child," he laughs delightedly. "Exactly!"

CodeMonkey

Possibly the OH but cannot self-identify

This is the title song from Frank Zappa's two album / three record play Joe's Garage.

Last edited:

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #1,337

The Roxy Music version was the wedding song for my wife and I back in 1985. The 10,000 Maniacs version is not quite as good imo but a good listen nonetheless.

CodeMonkey

Possibly the OH but cannot self-identify

RocknRam29

Live, Love, Laugh, & Learn

Dieter the Brock

Fourth responder

The Roxy Music version was the wedding song for my wife and I back in 1985. The 10,000 Maniacs version is not quite as good imo but a good listen nonetheless.

Bryan Ferry is my real dad - Him and Kurt Warner