Was there some sort of reason L.A. was not available in either year?'73 Rams record was 12-2 Dallas 10-4. We had to go to Dallas. In '74 Rams record 10-4 Viqueens 10-4 Rams beat the Viqueens earlier in the season therefore owning the tiebreaker. The NFL puts the game in Minn in the blowing snow.

Bud Grant's Garage Sale

- Thread starter Prime Time

- Start date

-

To unlock all of features of Rams On Demand please take a brief moment to register. Registering is not only quick and easy, it also allows you access to additional features such as live chat, private messaging, and a host of other apps exclusive to Rams On Demand.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

69superbowl

Rookie

Boffo, back in those dark ages, the NFL brass "rotated" home field for conference championship games. Ridiculous. I have always had the paranoid suspicion that Rozelle hated Carroll Rosenbloom for his affinity to go rogue and make himself a pain in Rozelle's ass, plus his allegiance and friendship with the other troublemaker, Al Davis (RIP, Cryptkeeper). Anyway, that's what I remember, I could be wrong.

Ah. Yeah, I'm glad it's determined by record now.Boffo, back in those dark ages, the NFL brass "rotated" home field for conference championship games. Ridiculous. I have always had the paranoid suspicion that Rozelle hated Carroll Rosenbloom for his affinity to go rogue and make himself a pain in Rozelle's ass, plus his allegiance and friendship with the other troublemaker, Al Davis (RIP, Cryptkeeper). Anyway, that's what I remember, I could be wrong.

Thanks for explaining, guys. I was genuinely curious.

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #24

At the doorstep of greatness

Garage sale celebrates Hall of Fame career, life of Vikings legend Bud Grant

By Ben Goessling | ESPN.com

BLOOMINGTON, Minn. -- The snowmobile suit from a charity event the Minnesota Vikings hold each February had already been marked down by 50 percent to $200. The panels of deflated footballs that Bud Grant had signed? There were stacks of those on a table in the Hall of Fame coach's driveway. And the origins of the fishing lure Greg Carlson had bought were too specious to make it anything more than a stocking stuffer with a good backstory.

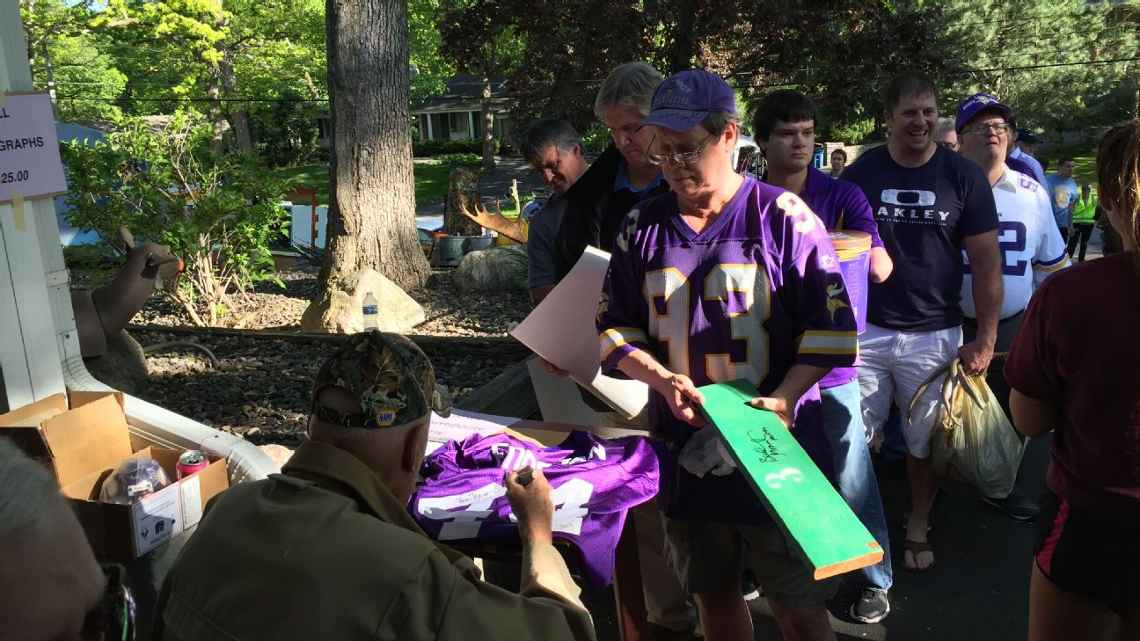

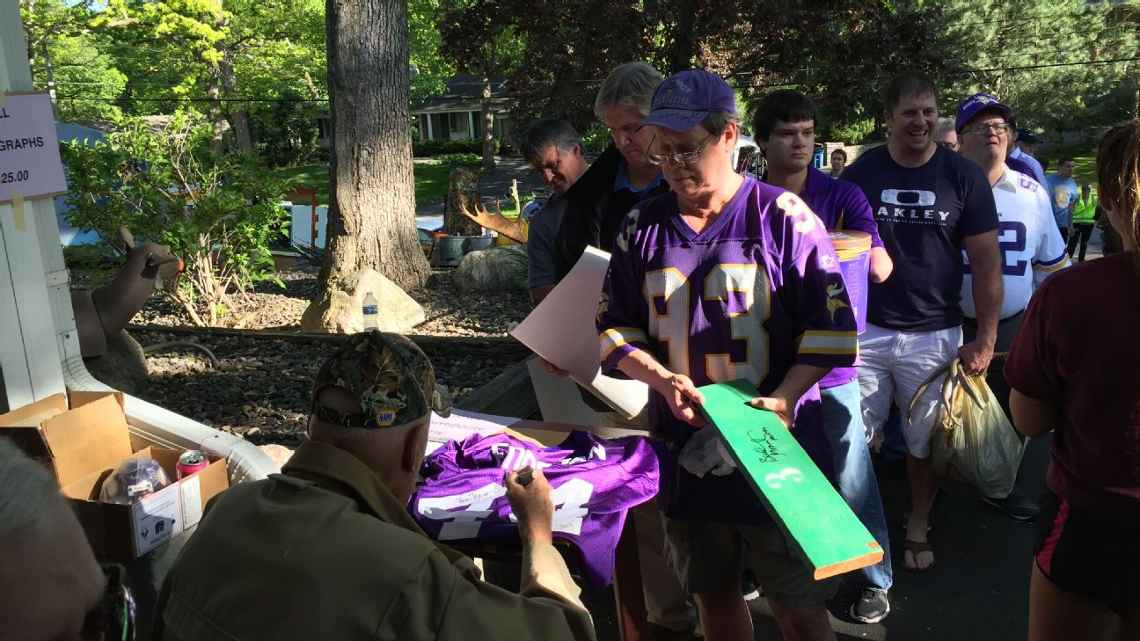

Ackerman + Gruber for ESPNSome people bought items not for their external value, but in order to share a story with Hall of Fame coach Bud Grant.

"He opened it up, and I asked him, 'Is this yours?'" Carlson said. "He goes, 'Do you know how old I am? Do you know how many fishing lures I had?' He seemed to think it was his. This is probably going to go as a gift."

Carlson wasn't rummaging through boxes in Grant's driveway last week on a hunt for collectibles so much as he was on a mission. His father, Paul, died last year at 67, and when Greg Carlson heard about Grant's three-day garage sale -- and how the greatest coach in Vikings history had promised an autograph to anybody who bought at least $25 worth of his stuff -- he remembered a conversation with his dad from a few years back.

"I had asked him, 'Is there anybody you'd really like to meet?'" Greg Carlson said. "He said, 'You know, Greg, if I were able to go fishing with Bud, just sit in the back of the boat, be quiet and listen to him talk, that'd be the tops for me.'"

What possessed Carlson to buy a couple hundred bucks' worth of Grant's keepsakes last Wednesday night, returning the next morning to have the items signed? What drove more than a hundred people to congregate on the edge of the 87-year-old coach's driveway last week, waiting for his whistle blast to signify they could step onto his property? For a few, maybe it was the chance to score a keepsake either rare (a signed photograph of the Minneapolis Lakers' 1950 NBA championship team) or bizarre (a walking stick fashioned from a bull's penis).

But for most, it seemed, the attraction was the chance to spend a few minutes with a man who's led a unique and historic life of sports achievements.

Grant is the only man to ever play in both the NBA and the NFL, winning the first championship in NBA history with the Minneapolis Lakers. While he was enlisted in the Navy during World War II, he played on a football team coached by Paul Brown. After finishing second in the NFL with 997 receiving yards in 1952, Grant became the first player in league history to play out his option, leaving the Philadelphia Eagles for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers. He later won four Grey Cups as a coach, returned to Minnesota to coach the Vikings to four Super Bowl appearances and became the first man inducted into both the Canadian Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Grant's 158 wins are the 14th most in NFL history. Add his 132 CFL wins and four Grey Cups and he's won more professional football games than anyone but Don Shula and George Halas. The Vikings' four Super Bowl losses probably kept Grant from being lionized nationally like Shula, Halas or Lombardi, but in Minnesota, he is an icon. His stoic visage on wintry days at Metropolitan Stadium, his ban of heaters on the sidelines and his insistence on a certain code of conduct -- down to making players practice standing at attention during the national anthem -- are all sources of deep local pride in a state of hardy and self-effacing people.

And yet, he's Grandpa Bud, who's lived in the same house since the Vikings hired him in 1967, who still keeps his old office at the team's facility (though he doesn't work for the Vikings in any official capacity) and whose son Mike has become the state's most successful high school coach. He is one of Minnesota's most visible outdoorsmen, hunting and fishing all over the Midwest and spending much of the summertime at his cabin in Gordon, Wisconsin, 40 miles south of his hometown on the shores of Lake Superior.

Grant maintains a loose grip on the artifacts from his life in sports, matter-of-factly dismissing the notion that they -- and he -- are worth the fuss they've received. He's passed along mementos to his six children over the years, and sold some others at his nine previous garage sales. Last week's event, which Grant promised would be his biggest and last, saw him part with what were presumably the final items he'd decided not to keep.

"There are things you've hung on your wall for 25 years," he said. "Well, maybe you don't want to look at it anymore. Are you going to put it behind the furnace, or are you going to sell it?"

But the stuff came with stories, so many that people stood in line to meet Grant for 90 minutes while he signed autographs and casually relayed his memories of the things they were buying. It was a fitting snapshot of a relationship between a coach and a community that still feels both reverent and familiar.

"I've been in the public domain for a long time," Grant said. "Everybody's really respectful. These are good people. They're good-hearted people. ... This is a little different here. I haven't coached since 1985. I still have an office with the Vikings, and I'm well-received there. I know everybody there. It's a family kind of a thing."

Blankets, coats and memories

Taken as a whole, the unique items at Grant's garage sale told the story of his distinct career, of a man who did what he wanted -- and succeeded at most of it -- at a time where the path to success in American sports was much less rigid than it is now.

Grant sold a plaque with a photograph of the Lakers' 1950 championship team, signed by himself and Basketball Hall of Famers George Mikan, Vern Mikkelsen and John Kundla, as well as a piece of the Lakers' practice floor from the old St. Joseph's Home for Children.

He sold a wool blanket he used to keep himself warm on the sidelines at the University of Minnesota's Memorial Stadium while he was an All-Big Ten receiver there in the late 1940s. Grant's oldest daughter, Kathy Fritz, said she and her siblings used to build forts under it, and added she was a bit surprised to see her father part with it. His Hudson's Bay wool coat, which Grant wore on the sidelines in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in the 1960s, was priced at $345. And Grant's banner from the Vikings' Ring of Honor -- which was returned to him after the Metrodome was demolished last winter -- fetched $2,100 in a silent auction after being displayed in his yard for three days to welcome shoppers.

There were architectural drawings for a proposed joint Vikings/Gophers stadium on the University of Minnesota campus, from before the idea was scrapped in favor of new stadiums for both teams. There were printed photographs from some of Grant's playoff victories, his headset from his final year coaching the Vikings and a rifle he had used on a hunting expedition. There was even one of Grant's old canoes, which he sold to Phil Schmidt and his son Kasey after signing it, "Bud Grant HOF '94."

But most of all, there was Grant himself, sitting at a table for three days to sign autographs, pose for pictures and tell stories, rarely leaving to eat lunch or use the restroom.

"There were the sports fans who were looking for specific memorabilia and hunting equipment," said Grant's daughter Laurie Tangert. "But I think some people just kind of picked up whatever to have something to bring to connect with him and get an autograph. Somebody said, 'Do you think he really does enjoy this?' I think he does enjoy interacting with the people he meets here."

The effect can be just as cathartic for Vikings fans who are old enough to remember the team's four Super Bowl trips from 1969 to 1976. The team has lost four NFC Championship Games since Grant retired -- two in overtime -- and as the Vikings prepare to move back outdoors for two seasons following 32 years in the charmless Metrodome, the footage of Grant roaming the Metropolitan Stadium sidelines, seemingly unperturbed by the Minnesota winters, has been romanticized even more than it previously was.

Darrin Eilertson, the 47-year-old Minneapolis attorney who bought Grant's old Hudson's Bay coat last week, plans to wear it to a Vikings game at TCF Bank Stadium during one of the next two seasons. That game, he said, would be his first since the Vikings' 30-27 overtime loss to the Atlanta Falcons in the NFC title game on Jan. 17, 1999. The defeat kept a 15-1 Vikings team from going to the Super Bowl for the first time since Grant coached. Eilertson canceled his season tickets a couple of months after the game.

"I'm ready to start fresh again," he said. "Now I've got some inspiration with Bud here, and we'll see if we can get locked into going to games again."

Staying young

It is not lost on Grant how rare it is as a coach to have never been fired, to have stayed in the same house for nearly 50 years and to have spent his life among people who are so much like him. But as he's gotten older, Tangert said, his stoicism has started to crack.

"He's gotten very, very emotional," Tangert said. "It seems like there have been several events over the last few years -- the 50th-year celebration of the Vikings [in 2010], they honored him at a Gophers game -- just several things where he's gotten very choked up. I think it's meant a great deal to him. [In the past], he might have been feeling it, but we didn't see it."

That change, Tangert suspects, probably has to do with her father's deepest sorrows over letting something go, and one of his brightest moments in getting something back.

His wife, Pat, died of complications from Parkinson's disease in March 2009, and was buried that spring at the family's cabin in northwest Wisconsin. The two had been married for 59 years, and Pat Grant was the linchpin of the family, throwing birthday parties for her six kids until they were well into their 40s and doting on the Grants' 19 grandchildren.

But a chance encounter at Vikings training camp -- through a mutual friend Grant was talking to about duck decoys, of all things -- introduced Grant to Pat Smith, a retired teacher who'd been attending Vikings games since Grant was the coach. She shared many of his interests, and Grant eventually asked her out to dinner, beginning a relationship that has blossomed over the years.

Smith still has a house in Mankato, where the Vikings train each summer and where she still works eight days a month as a substitute teacher. She makes the 75-mile drive from Mankato to Bloomington several times a week during the school year, and the two spend much of the summer at the Grants' cabin.

She chides his kids for not refilling ice trays; he gives her a hard time about watching too many NFL games. They travel around the Twin Cities to watch Grant's 10 great-grandchildren play T-ball, and she texts updates from Mike's football games to Grant's 19 grandchildren. "We just got into it easily, and pretty soon, it's like, I felt like I've known him all my life," Smith said.

She had plans to get married until her fiancé died in the Vietnam War, and she'd lived alone from that time until she met Grant. Now, Smith has become an important part of his family.

"He was really, really down after my mom died," Tangert said. "Even though it was hard, it was great to see him take renewed interest in life and feel that energy."

Even though she predicts Grant could live at least another 10 years, Smith worries about what life will be like when he's gone. Smith had told Grant they didn't need to get married, and she's kept her house in Mankato for the day she's living alone again. "Sometimes I'm scared that I'm going to wake up in the morning and he's not going to wake up," she said.

But that day isn't here yet. These days are filled with activity, with family events and fishing trips. "It's been a blessing to have another companion who keeps you going," Grant said. "When you've got a young family, and you're talking to your kids or your grandkids, the conversations are young. You're thinking young. You're not thinking about who died. You're not thinking about who's sick. You're not thinking about all the things you can't do. You're talking about your grandkids, you're talking about their life. It keeps you young. It's not a morbid existence at all. It could end tomorrow, but it's a great run."

The keepsakes from that run? Somebody else can have those. The memories are what mean the most anyway.

Bud Grant didn't sell everything

Vikings legend isn't sentimental, but some coaching mementos weren't for sale

By Ben Goessling | ESPN.com

BLOOMINGTON, Minn. -- It shouldn't be assumed that the items still in Bud Grant's basement, the ones commemorating some of the greatest moments in Minnesota Vikings history, are necessarily still there for some transcendent reason. Or at least not any the Hall of Fame coach will admit.

After his three-day garage sale last week, Grant still has just two obvious tributes to his 18 seasons with the Vikings: a room with paintings and pictures given to him over the course of his career, and a wood-paneled built-in shelf with a replica of his Hall of Fame bust, his 1969 NFL Coach of the Year trophy and game balls from his most significant victories. They're still there, the 87-year-old coach said last week, because they're the ones his six kids, 19 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren didn't break.

That's it?

"That's it," Grant said.

A tour of Grant's house, decorated with animal pelts and antler racks from all over the world, shows his love of the outdoors is still his biggest passion. He doesn't watch many NFL games, but he'll watch "every hunting and fishing show on TV," said Pat Smith, the woman who has been Grant's committed companion for several years.

But while his memorabilia might still be there because of durability, the items probably got put on display in his house in the first place because of their significance. There's a game ball from Grant's 150th NFL win, over the Pittsburgh Steelers on Nov. 20, 1983. There's a ball from his 200th professional win (counting his victories in the Canadian Football League), which came over the Miami Dolphins on Dec. 11, 1976. Grant also has the ball from his first career victory, which came Oct. 15, 1967, over the Green Bay Packers -- and Vince Lombardi.

Ackerman + Gruber for ESPN Bud Grant sold a lot of his memorabilia at a garage sale, but footballs commemorating his most significant victories remain on a shelf in his Bloomington, Minn., home.

"That was a funny story," said Chad Ostlund, who's been a close friend of Grant's for years and worked in the Vikings' front office from 1995 to 2005. "[Former coach] Mike Tice was in the hallway in 2002, and he goes, 'Hey, look at this, Bud. They made this thing for me, with the game program and the ticket and all this stuff [from Tice's first win over the Detroit Lions].' [Bud] goes, 'Well, who'd you beat?' [Tice] goes, 'Well, Marty Mornhinweg.' Bud's sitting there and he goes, 'Well, I beat Lombardi.'

"I think at that point, Tice went from 6-foot-8 to 4-foot-8 in about two seconds."

During the sale, though, Ostlund said Grant did float the idea of selling the game balls, but the two quickly decided against it. His sale last week was the 10th one he's held, and Grant has given each of his children items from his coaching career over the years.

"We all have special things," said Kathy Fritz, Grant's oldest daughter, "and there's lots more. I think he's digging deeper this time, but there's so much stuff, and the special stuff is not out there [on sale]."

Garage sale celebrates Hall of Fame career, life of Vikings legend Bud Grant

By Ben Goessling | ESPN.com

BLOOMINGTON, Minn. -- The snowmobile suit from a charity event the Minnesota Vikings hold each February had already been marked down by 50 percent to $200. The panels of deflated footballs that Bud Grant had signed? There were stacks of those on a table in the Hall of Fame coach's driveway. And the origins of the fishing lure Greg Carlson had bought were too specious to make it anything more than a stocking stuffer with a good backstory.

Ackerman + Gruber for ESPNSome people bought items not for their external value, but in order to share a story with Hall of Fame coach Bud Grant.

"He opened it up, and I asked him, 'Is this yours?'" Carlson said. "He goes, 'Do you know how old I am? Do you know how many fishing lures I had?' He seemed to think it was his. This is probably going to go as a gift."

Carlson wasn't rummaging through boxes in Grant's driveway last week on a hunt for collectibles so much as he was on a mission. His father, Paul, died last year at 67, and when Greg Carlson heard about Grant's three-day garage sale -- and how the greatest coach in Vikings history had promised an autograph to anybody who bought at least $25 worth of his stuff -- he remembered a conversation with his dad from a few years back.

"I had asked him, 'Is there anybody you'd really like to meet?'" Greg Carlson said. "He said, 'You know, Greg, if I were able to go fishing with Bud, just sit in the back of the boat, be quiet and listen to him talk, that'd be the tops for me.'"

What possessed Carlson to buy a couple hundred bucks' worth of Grant's keepsakes last Wednesday night, returning the next morning to have the items signed? What drove more than a hundred people to congregate on the edge of the 87-year-old coach's driveway last week, waiting for his whistle blast to signify they could step onto his property? For a few, maybe it was the chance to score a keepsake either rare (a signed photograph of the Minneapolis Lakers' 1950 NBA championship team) or bizarre (a walking stick fashioned from a bull's penis).

But for most, it seemed, the attraction was the chance to spend a few minutes with a man who's led a unique and historic life of sports achievements.

Grant is the only man to ever play in both the NBA and the NFL, winning the first championship in NBA history with the Minneapolis Lakers. While he was enlisted in the Navy during World War II, he played on a football team coached by Paul Brown. After finishing second in the NFL with 997 receiving yards in 1952, Grant became the first player in league history to play out his option, leaving the Philadelphia Eagles for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers. He later won four Grey Cups as a coach, returned to Minnesota to coach the Vikings to four Super Bowl appearances and became the first man inducted into both the Canadian Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Grant's 158 wins are the 14th most in NFL history. Add his 132 CFL wins and four Grey Cups and he's won more professional football games than anyone but Don Shula and George Halas. The Vikings' four Super Bowl losses probably kept Grant from being lionized nationally like Shula, Halas or Lombardi, but in Minnesota, he is an icon. His stoic visage on wintry days at Metropolitan Stadium, his ban of heaters on the sidelines and his insistence on a certain code of conduct -- down to making players practice standing at attention during the national anthem -- are all sources of deep local pride in a state of hardy and self-effacing people.

And yet, he's Grandpa Bud, who's lived in the same house since the Vikings hired him in 1967, who still keeps his old office at the team's facility (though he doesn't work for the Vikings in any official capacity) and whose son Mike has become the state's most successful high school coach. He is one of Minnesota's most visible outdoorsmen, hunting and fishing all over the Midwest and spending much of the summertime at his cabin in Gordon, Wisconsin, 40 miles south of his hometown on the shores of Lake Superior.

Grant maintains a loose grip on the artifacts from his life in sports, matter-of-factly dismissing the notion that they -- and he -- are worth the fuss they've received. He's passed along mementos to his six children over the years, and sold some others at his nine previous garage sales. Last week's event, which Grant promised would be his biggest and last, saw him part with what were presumably the final items he'd decided not to keep.

"There are things you've hung on your wall for 25 years," he said. "Well, maybe you don't want to look at it anymore. Are you going to put it behind the furnace, or are you going to sell it?"

But the stuff came with stories, so many that people stood in line to meet Grant for 90 minutes while he signed autographs and casually relayed his memories of the things they were buying. It was a fitting snapshot of a relationship between a coach and a community that still feels both reverent and familiar.

"I've been in the public domain for a long time," Grant said. "Everybody's really respectful. These are good people. They're good-hearted people. ... This is a little different here. I haven't coached since 1985. I still have an office with the Vikings, and I'm well-received there. I know everybody there. It's a family kind of a thing."

Blankets, coats and memories

Taken as a whole, the unique items at Grant's garage sale told the story of his distinct career, of a man who did what he wanted -- and succeeded at most of it -- at a time where the path to success in American sports was much less rigid than it is now.

Grant sold a plaque with a photograph of the Lakers' 1950 championship team, signed by himself and Basketball Hall of Famers George Mikan, Vern Mikkelsen and John Kundla, as well as a piece of the Lakers' practice floor from the old St. Joseph's Home for Children.

He sold a wool blanket he used to keep himself warm on the sidelines at the University of Minnesota's Memorial Stadium while he was an All-Big Ten receiver there in the late 1940s. Grant's oldest daughter, Kathy Fritz, said she and her siblings used to build forts under it, and added she was a bit surprised to see her father part with it. His Hudson's Bay wool coat, which Grant wore on the sidelines in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in the 1960s, was priced at $345. And Grant's banner from the Vikings' Ring of Honor -- which was returned to him after the Metrodome was demolished last winter -- fetched $2,100 in a silent auction after being displayed in his yard for three days to welcome shoppers.

There were architectural drawings for a proposed joint Vikings/Gophers stadium on the University of Minnesota campus, from before the idea was scrapped in favor of new stadiums for both teams. There were printed photographs from some of Grant's playoff victories, his headset from his final year coaching the Vikings and a rifle he had used on a hunting expedition. There was even one of Grant's old canoes, which he sold to Phil Schmidt and his son Kasey after signing it, "Bud Grant HOF '94."

But most of all, there was Grant himself, sitting at a table for three days to sign autographs, pose for pictures and tell stories, rarely leaving to eat lunch or use the restroom.

"There were the sports fans who were looking for specific memorabilia and hunting equipment," said Grant's daughter Laurie Tangert. "But I think some people just kind of picked up whatever to have something to bring to connect with him and get an autograph. Somebody said, 'Do you think he really does enjoy this?' I think he does enjoy interacting with the people he meets here."

The effect can be just as cathartic for Vikings fans who are old enough to remember the team's four Super Bowl trips from 1969 to 1976. The team has lost four NFC Championship Games since Grant retired -- two in overtime -- and as the Vikings prepare to move back outdoors for two seasons following 32 years in the charmless Metrodome, the footage of Grant roaming the Metropolitan Stadium sidelines, seemingly unperturbed by the Minnesota winters, has been romanticized even more than it previously was.

Darrin Eilertson, the 47-year-old Minneapolis attorney who bought Grant's old Hudson's Bay coat last week, plans to wear it to a Vikings game at TCF Bank Stadium during one of the next two seasons. That game, he said, would be his first since the Vikings' 30-27 overtime loss to the Atlanta Falcons in the NFC title game on Jan. 17, 1999. The defeat kept a 15-1 Vikings team from going to the Super Bowl for the first time since Grant coached. Eilertson canceled his season tickets a couple of months after the game.

"I'm ready to start fresh again," he said. "Now I've got some inspiration with Bud here, and we'll see if we can get locked into going to games again."

Staying young

It is not lost on Grant how rare it is as a coach to have never been fired, to have stayed in the same house for nearly 50 years and to have spent his life among people who are so much like him. But as he's gotten older, Tangert said, his stoicism has started to crack.

"He's gotten very, very emotional," Tangert said. "It seems like there have been several events over the last few years -- the 50th-year celebration of the Vikings [in 2010], they honored him at a Gophers game -- just several things where he's gotten very choked up. I think it's meant a great deal to him. [In the past], he might have been feeling it, but we didn't see it."

That change, Tangert suspects, probably has to do with her father's deepest sorrows over letting something go, and one of his brightest moments in getting something back.

His wife, Pat, died of complications from Parkinson's disease in March 2009, and was buried that spring at the family's cabin in northwest Wisconsin. The two had been married for 59 years, and Pat Grant was the linchpin of the family, throwing birthday parties for her six kids until they were well into their 40s and doting on the Grants' 19 grandchildren.

But a chance encounter at Vikings training camp -- through a mutual friend Grant was talking to about duck decoys, of all things -- introduced Grant to Pat Smith, a retired teacher who'd been attending Vikings games since Grant was the coach. She shared many of his interests, and Grant eventually asked her out to dinner, beginning a relationship that has blossomed over the years.

Smith still has a house in Mankato, where the Vikings train each summer and where she still works eight days a month as a substitute teacher. She makes the 75-mile drive from Mankato to Bloomington several times a week during the school year, and the two spend much of the summer at the Grants' cabin.

She chides his kids for not refilling ice trays; he gives her a hard time about watching too many NFL games. They travel around the Twin Cities to watch Grant's 10 great-grandchildren play T-ball, and she texts updates from Mike's football games to Grant's 19 grandchildren. "We just got into it easily, and pretty soon, it's like, I felt like I've known him all my life," Smith said.

She had plans to get married until her fiancé died in the Vietnam War, and she'd lived alone from that time until she met Grant. Now, Smith has become an important part of his family.

"He was really, really down after my mom died," Tangert said. "Even though it was hard, it was great to see him take renewed interest in life and feel that energy."

Even though she predicts Grant could live at least another 10 years, Smith worries about what life will be like when he's gone. Smith had told Grant they didn't need to get married, and she's kept her house in Mankato for the day she's living alone again. "Sometimes I'm scared that I'm going to wake up in the morning and he's not going to wake up," she said.

But that day isn't here yet. These days are filled with activity, with family events and fishing trips. "It's been a blessing to have another companion who keeps you going," Grant said. "When you've got a young family, and you're talking to your kids or your grandkids, the conversations are young. You're thinking young. You're not thinking about who died. You're not thinking about who's sick. You're not thinking about all the things you can't do. You're talking about your grandkids, you're talking about their life. It keeps you young. It's not a morbid existence at all. It could end tomorrow, but it's a great run."

The keepsakes from that run? Somebody else can have those. The memories are what mean the most anyway.

Bud Grant didn't sell everything

Vikings legend isn't sentimental, but some coaching mementos weren't for sale

By Ben Goessling | ESPN.com

BLOOMINGTON, Minn. -- It shouldn't be assumed that the items still in Bud Grant's basement, the ones commemorating some of the greatest moments in Minnesota Vikings history, are necessarily still there for some transcendent reason. Or at least not any the Hall of Fame coach will admit.

After his three-day garage sale last week, Grant still has just two obvious tributes to his 18 seasons with the Vikings: a room with paintings and pictures given to him over the course of his career, and a wood-paneled built-in shelf with a replica of his Hall of Fame bust, his 1969 NFL Coach of the Year trophy and game balls from his most significant victories. They're still there, the 87-year-old coach said last week, because they're the ones his six kids, 19 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren didn't break.

That's it?

"That's it," Grant said.

A tour of Grant's house, decorated with animal pelts and antler racks from all over the world, shows his love of the outdoors is still his biggest passion. He doesn't watch many NFL games, but he'll watch "every hunting and fishing show on TV," said Pat Smith, the woman who has been Grant's committed companion for several years.

But while his memorabilia might still be there because of durability, the items probably got put on display in his house in the first place because of their significance. There's a game ball from Grant's 150th NFL win, over the Pittsburgh Steelers on Nov. 20, 1983. There's a ball from his 200th professional win (counting his victories in the Canadian Football League), which came over the Miami Dolphins on Dec. 11, 1976. Grant also has the ball from his first career victory, which came Oct. 15, 1967, over the Green Bay Packers -- and Vince Lombardi.

Ackerman + Gruber for ESPN Bud Grant sold a lot of his memorabilia at a garage sale, but footballs commemorating his most significant victories remain on a shelf in his Bloomington, Minn., home.

"That was a funny story," said Chad Ostlund, who's been a close friend of Grant's for years and worked in the Vikings' front office from 1995 to 2005. "[Former coach] Mike Tice was in the hallway in 2002, and he goes, 'Hey, look at this, Bud. They made this thing for me, with the game program and the ticket and all this stuff [from Tice's first win over the Detroit Lions].' [Bud] goes, 'Well, who'd you beat?' [Tice] goes, 'Well, Marty Mornhinweg.' Bud's sitting there and he goes, 'Well, I beat Lombardi.'

"I think at that point, Tice went from 6-foot-8 to 4-foot-8 in about two seconds."

During the sale, though, Ostlund said Grant did float the idea of selling the game balls, but the two quickly decided against it. His sale last week was the 10th one he's held, and Grant has given each of his children items from his coaching career over the years.

"We all have special things," said Kathy Fritz, Grant's oldest daughter, "and there's lots more. I think he's digging deeper this time, but there's so much stuff, and the special stuff is not out there [on sale]."

Bud Grant authored one of my favorite quotes about overworking as a coach,went something like this:

"You can coach the perfect game but that ball isn't round and it bounces funny and you still lose"

He was known for working forty and goin home

"You can coach the perfect game but that ball isn't round and it bounces funny and you still lose"

He was known for working forty and goin home

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #26

http://profootballtalk.nbcsports.co...ar-another-bud-grant-garage-sale-spectacular/

Another year, another Bud Grant Garage Sale Spectacular

Posted by Mike Wilkening on May 21, 2015

AP

AP

Former Vikings head coach Bud Grant is having yet another garage sale.

And he has a Twitter account to tell you about it.

Yes, the 88-year-old Hall of Famer has a verified Twitter account, but he’s using it only to get the word out about the garage sale, as he told Chris Tomasson of the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

“I opened it out of necessity. I was looking at the want ads in your paper, and nobody buys the paper for the want ads anymore,” Grant said, according to the Pioneer Press. “So I had to find a way to advertise and get out the word. I opened a Twitter account, and I’ll close it as soon as the garage sale ends.”

So about this garage sale: it began Wednesday — Grant’s birthday — and it runs through Friday. Both hunting enthusiasts and Vikings fans would appear to have to some options. As a 1990s kid, this Starter jacket looks especially appealing. And really, you can’t really attach a value to this, or this.

Grant had a garage sale last year, so this year’s sale is indeed a pleasant surprise.

And it appears there’s plenty of interesting stuff from which to choose.

Especially that Starter jacket.

Another year, another Bud Grant Garage Sale Spectacular

Posted by Mike Wilkening on May 21, 2015

Former Vikings head coach Bud Grant is having yet another garage sale.

And he has a Twitter account to tell you about it.

Yes, the 88-year-old Hall of Famer has a verified Twitter account, but he’s using it only to get the word out about the garage sale, as he told Chris Tomasson of the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

“I opened it out of necessity. I was looking at the want ads in your paper, and nobody buys the paper for the want ads anymore,” Grant said, according to the Pioneer Press. “So I had to find a way to advertise and get out the word. I opened a Twitter account, and I’ll close it as soon as the garage sale ends.”

So about this garage sale: it began Wednesday — Grant’s birthday — and it runs through Friday. Both hunting enthusiasts and Vikings fans would appear to have to some options. As a 1990s kid, this Starter jacket looks especially appealing. And really, you can’t really attach a value to this, or this.

Grant had a garage sale last year, so this year’s sale is indeed a pleasant surprise.

And it appears there’s plenty of interesting stuff from which to choose.

Especially that Starter jacket.

That viqueen muskie is uglier than hell.

Sure is tough seeing one of Thor's posts from a year ago right above.

Sure is tough seeing one of Thor's posts from a year ago right above.

Love that story Elm!Elmgrovegnome with a tale of serendipity:

My older brother, Roy loved the Cowboys in the 70's. And much to my dismay, my younger brother Danny, liked whatever Roy liked. I refused to adopt their team, out of spite and I didn't know much about football back in the early 70's. I was only 5 or 6. So my sister decided she and I should pick the other NFC playoff teams and root against the Cowboys and my brothers. She chose Minnesota because of their purple uniforms. So that left me with the Rams....good thing I already liked their uniforms. A lifelong fan as born. I'm glad the Rams didn't wear purple.

Thanks... bring back some of the bitterest memories as a Rams fan I have.

I remember throwing myself on the floor and crying in 1969 when they lost to the Bud Grant led Vikings.

Scoring

RAMMIN

1stRamsBob Klein 3 yard pass from Roman Gabriel (Bruce Gossett kick)70

VikingsDave Osborn 1 yard rush (Fred Cox kick)77

2ndRamsBruce Gossett 20 yard field goal 107

RamsBilly Truax 2 yard pass from Roman Gabriel (Bruce Gossett kick)177

3rdVikingsDave Osborn 1 yard rush (Fred Cox kick)1714

4thRamsBruce Gossett 27 yard field goal 2014

VikingsJoe Kapp 2 yard rush (Fred Cox kick)2021

VikingsSafety, Gabriel tackled in end zone by Eller 20

23

I remember throwing myself on the floor and crying in 1969 when they lost to the Bud Grant led Vikings.

Scoring

RAMMIN

1stRamsBob Klein 3 yard pass from Roman Gabriel (Bruce Gossett kick)70

VikingsDave Osborn 1 yard rush (Fred Cox kick)77

2ndRamsBruce Gossett 20 yard field goal 107

RamsBilly Truax 2 yard pass from Roman Gabriel (Bruce Gossett kick)177

3rdVikingsDave Osborn 1 yard rush (Fred Cox kick)1714

4thRamsBruce Gossett 27 yard field goal 2014

VikingsJoe Kapp 2 yard rush (Fred Cox kick)2021

VikingsSafety, Gabriel tackled in end zone by Eller 20

23

Many times as a youngster those Vikings made me very mad. I've never forgiven them and I especially relished the beating the GSOT gave them in the 99 playoffs.

I've always felt they were #2 to the 49ers on the "freak them" list because of those post season losses.

I'll wait for Selassie to chime in here.....I know it's coming hahaha.

Several of those games were hard to take.

Especially when it was reasonably clear the Rams were the better team on at least two or three of those losses.

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #31

Sure is tough seeing one of Thor's posts from a year ago right above.

Understood but he lives on here through his posts. Went through some of our pm conversations today so I don't forget what he meant to me.

Exactly. What Grant and the Vikings did to the Rams in those playoff losses between 69 and 77 is only a thorn in the side of us old-timers who had to endure those losses. The Cowboys are close behind in that category.

the Rams either lost to dallass or minnyhaha every flippin year. the worst part is that they were capable of beating the steelers , broncos, raiders as well. never understood how they didnt have home games with the better record. of course, sadly enough, the mudbowl kinda kills that argument. (how on earth does it rain in LA when they finally get a home playoff game ??

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #33

http://mmqb.si.com/mmqb/2016/05/17/bud-grant-yard-sale-minnesota-nfl-mailbag

Bud Grant’s Annual Yard Sale: ‘We Got Fishing Lures!’

For the past 11 years, the former Vikings coach has invited the public to his home in Minnesota to sift through clothes, canoes and other crapola. The Hall of Famer hosts No. 12 this week and turns 89.

Peter King

Bud Grant’s annual yard sale in Minneapolis draws thousands from around the region.

Jim Mone/AP

Mark Hamilton, a retired owner of five wildlife galleries in North Dakota, will get up this morning and drive nine hours—506 miles—from Minot, N.D., to 8134 Oakmere Road in Minneapolis, so he can go to a yard sale.

A yard sale. Bud Grant’s yard sale.

“Nowhere else in America can this happen,” Hamilton said Tuesday, preparing for his long journey. “Bud’s a Minnesota boy, and he’s revered. He’s not just a Minnesota treasure. He’s a national treasure. Cars are backed up on both sides of the road, and all they want to do is rub shoulders with an icon.”

And buy stuff. Grant, the Hall of Fame football coach who has not been in any sort of limelight since retiring as Vikings coach 31 years ago, turns 89 on Friday. He’ll celebrate by having 5,000 of his closest friends (best guess) over to his house on Oakmere Road for a real, live yard sale, for the 12th spring in a row.

You know, with tools and kids’ clothes and hunting clothes and books and memorabilia and outdoorsy stuff like canoes and snowmobile suits. Why? A man’s got to live; the Hall of Fame bust and $4.85 will buy you a latte at Caribou Coffee.

Today at 5 p.m., Grant will blow a whistle—his old coach’s whistle, in fact—and somewhere between 500 and 1,000 early arrivers will flood his yard. No one can come onto the property until 5 p.m. exactly. “They’ll be respectful,” Grant said Tuesday. “We’re Minnesotans now, not New Yorkers.”

The crowds will come from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Thursday, and then 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. Friday, to look over the stuff deemed expendable from Grant, his six children, 19 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren (his wife is deceased), spread far and wide on the lawn and in the garage.

The renowned outdoorsman in Minnesota, the Dakotas, Manitoba and Saskatchewan wants to deal his hunting and fishing and sailing stuff this week.

“Got some canoes this year,” he said, and he must: He mentioned canoes four times in 24 minutes on the phone. “And paddles, and all sorts of fishing equipment. You want fishing lures? We got fishing lures!”

Cash and checks only. “In 12 years, I haven’t had a bad check yet,” Grant said.

There will be no discounts. Almost none, anyway. “The prices are as marked,” he said. “I don’t discount. I tell people, ‘If you don’t want to pay the marked price, you must not want it very much.”

Mark Hamilton, a longtime friend who has been hunting and fishing with Grant, can testify to that. “Bud,’’ he said from North Dakota, “would pinch a penny till it hollered.”

So I’ve seen some photos of the event from past years. It’s a good old-fashioned garage sale. Stuff scattered everywhere. And not overpriced. Lots of free clothes he’s been given over the years, particularly outdoors stuff and Vikings stuff. What’s he going to do? Die with all of it in the cellar?

Grant uses the money to finance his retirement, and his extended family gets some cash too. If it doesn’t sell one year, Grant puts it back inside—just like a regular American hoarder—and waits until the following May. A few years ago, he had a massive chest of drawers that didn’t sell for a couple of years, and he wouldn’t mark it down. It was heavy as hell. The next year, though, it went in the first hour of the first day. Full price.

Photo: Jim Mone/AP

An extra $20 will get you a Bud Grant autograph on your purchase. Yup, even rifles.

“You know, you keep stuff for so long,” he said. “You get tired of looking at it. You just want someone to take it off your hands. But I won’t give it away. I was raised poor, you know. Everything has value.”

Some people just want to come and listen to Grant tell a story. Which he’ll do. He’ll sign an autograph too. If a shirt’s $20, it’ll be $40 with a Grant signature. If you don’t want to buy anything, that’s fine. He’s good with a conversation, or posing for a photo.

“Imagine this,” said Bob Hagan, the Vikings’ long-time PR czar. “He’s the most famous person in the state, a guy you’ve loved for years, and here he is, inviting you into his yard once a year. Stay as long as you want. Who does that?”

I am only angry I can’t be there today. If Grant has a garage sale next year, I can tell you this: I’ll be at 8134 Oakmere.

Last thing: I said Grant won’t discount. Don’t tell anyone, but he discounted something for his pal Mark Hamilton a year ago. “When the Metrodome got torn down, they took the banners from the inside there, and Bud was auctioning off the BUD GRANT banner. It was supposed to be $2,000. And...”

And?

“Well,” Hamilton said, a bit uncomfortably, “I got it for about nothing. I mean, we’ve been friends … and I will just tell you, there is nobody like Bud. That is Bud.”

Evidently.

Bud Grant’s Annual Yard Sale: ‘We Got Fishing Lures!’

For the past 11 years, the former Vikings coach has invited the public to his home in Minnesota to sift through clothes, canoes and other crapola. The Hall of Famer hosts No. 12 this week and turns 89.

Peter King

Bud Grant’s annual yard sale in Minneapolis draws thousands from around the region.

Jim Mone/AP

Mark Hamilton, a retired owner of five wildlife galleries in North Dakota, will get up this morning and drive nine hours—506 miles—from Minot, N.D., to 8134 Oakmere Road in Minneapolis, so he can go to a yard sale.

A yard sale. Bud Grant’s yard sale.

“Nowhere else in America can this happen,” Hamilton said Tuesday, preparing for his long journey. “Bud’s a Minnesota boy, and he’s revered. He’s not just a Minnesota treasure. He’s a national treasure. Cars are backed up on both sides of the road, and all they want to do is rub shoulders with an icon.”

And buy stuff. Grant, the Hall of Fame football coach who has not been in any sort of limelight since retiring as Vikings coach 31 years ago, turns 89 on Friday. He’ll celebrate by having 5,000 of his closest friends (best guess) over to his house on Oakmere Road for a real, live yard sale, for the 12th spring in a row.

You know, with tools and kids’ clothes and hunting clothes and books and memorabilia and outdoorsy stuff like canoes and snowmobile suits. Why? A man’s got to live; the Hall of Fame bust and $4.85 will buy you a latte at Caribou Coffee.

Today at 5 p.m., Grant will blow a whistle—his old coach’s whistle, in fact—and somewhere between 500 and 1,000 early arrivers will flood his yard. No one can come onto the property until 5 p.m. exactly. “They’ll be respectful,” Grant said Tuesday. “We’re Minnesotans now, not New Yorkers.”

The crowds will come from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Thursday, and then 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. Friday, to look over the stuff deemed expendable from Grant, his six children, 19 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren (his wife is deceased), spread far and wide on the lawn and in the garage.

The renowned outdoorsman in Minnesota, the Dakotas, Manitoba and Saskatchewan wants to deal his hunting and fishing and sailing stuff this week.

“Got some canoes this year,” he said, and he must: He mentioned canoes four times in 24 minutes on the phone. “And paddles, and all sorts of fishing equipment. You want fishing lures? We got fishing lures!”

Cash and checks only. “In 12 years, I haven’t had a bad check yet,” Grant said.

There will be no discounts. Almost none, anyway. “The prices are as marked,” he said. “I don’t discount. I tell people, ‘If you don’t want to pay the marked price, you must not want it very much.”

Mark Hamilton, a longtime friend who has been hunting and fishing with Grant, can testify to that. “Bud,’’ he said from North Dakota, “would pinch a penny till it hollered.”

So I’ve seen some photos of the event from past years. It’s a good old-fashioned garage sale. Stuff scattered everywhere. And not overpriced. Lots of free clothes he’s been given over the years, particularly outdoors stuff and Vikings stuff. What’s he going to do? Die with all of it in the cellar?

Grant uses the money to finance his retirement, and his extended family gets some cash too. If it doesn’t sell one year, Grant puts it back inside—just like a regular American hoarder—and waits until the following May. A few years ago, he had a massive chest of drawers that didn’t sell for a couple of years, and he wouldn’t mark it down. It was heavy as hell. The next year, though, it went in the first hour of the first day. Full price.

Photo: Jim Mone/AP

An extra $20 will get you a Bud Grant autograph on your purchase. Yup, even rifles.

“You know, you keep stuff for so long,” he said. “You get tired of looking at it. You just want someone to take it off your hands. But I won’t give it away. I was raised poor, you know. Everything has value.”

Some people just want to come and listen to Grant tell a story. Which he’ll do. He’ll sign an autograph too. If a shirt’s $20, it’ll be $40 with a Grant signature. If you don’t want to buy anything, that’s fine. He’s good with a conversation, or posing for a photo.

“Imagine this,” said Bob Hagan, the Vikings’ long-time PR czar. “He’s the most famous person in the state, a guy you’ve loved for years, and here he is, inviting you into his yard once a year. Stay as long as you want. Who does that?”

I am only angry I can’t be there today. If Grant has a garage sale next year, I can tell you this: I’ll be at 8134 Oakmere.

Last thing: I said Grant won’t discount. Don’t tell anyone, but he discounted something for his pal Mark Hamilton a year ago. “When the Metrodome got torn down, they took the banners from the inside there, and Bud was auctioning off the BUD GRANT banner. It was supposed to be $2,000. And...”

And?

“Well,” Hamilton said, a bit uncomfortably, “I got it for about nothing. I mean, we’ve been friends … and I will just tell you, there is nobody like Bud. That is Bud.”

Evidently.

Hate is not a strong enough description for my feelings on the purple queens.

Roman Snow

H.I.M.

If anyone makes that yard sale (I actually lived in Bloomington for 3 years as a kid) could someone look for my bloody heart the viqueens ripped out of my chest during those '70s playoff games? I'll pay you back.

:burp:"Yeah, I'll put it in an ice chest, er somethin' ".

:rant:Screw that Mick Tinglehoff! ...and Paul Krause too!

:burp:"Yeah, I'll put it in an ice chest, er somethin' ".

:rant:Screw that Mick Tinglehoff! ...and Paul Krause too!

Did you really have to dredge up all those Bad Memories! Next thing you know you'll put up photos or something!!Dec. 17, 1969 - NFL West Championship - Minnesota 23, L.A. Rams 20

Dec. 29, 1974 - NFC Championship - Minnesota 14, L.A. Rams 10

Dec. 26, 1976 - NFL Championship - Minnesota 24, L.A. Rams 13

Dec. 26, 1977 - NFC Divisional - Minnesota 14, L.A. Rams 7

Dec. 31, 1978 - NFC Divisional - L.A. Rams 34, Minnesota 10

I don't know who Deacon, and Merlin hated playing more, The Colts or the Vikes! But my money is on the Vikings!

At Least the "Choke-Artists" Never Won a Super Bowl!

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #37

http://profootballtalk.nbcsports.co...p-for-his-final-garage-sale-with-bobbleheads/

Bud Grant gearing up for his final garage sale, with bobbleheads

Posted by Darin Gantt on April 21, 2017

Getty Images

Getty Images

Former Vikings coach Bud Grant’s garage sales have become almost as famous as his coaching career.

But about to turn 90, Grant said the one coming up next month will be his last. The reason why is as pragmatic as Grant himself.

“I’m running out of stuff,” he said, via Chris Tomasson of the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

For years he’s sold hunting and fishing gear and Vikings and NFL memorabilia from his Bloomington home, refusing to haggle over prices and offering whoever wanders up a chance to go through his stuff.

But picked-through as his collection might be, he’ll have a new item this year — a custom bobblehead doll.

“They’ve been after me for a bobblehead doll for years, and I just never felt the need to do that,’’ Grant said. “It’s an ego-trip kind of thing. But somebody suggested to have them at your garage sale to advertise. You’ve got to have a hook.

“You can’t just say, ‘Come to my garage sale and buy baby clothes.’ ’’

The bobblehead features Grant alongside his late hunting dog Boom, who died last October after a bout with cancer.

“I loved him dearly,’’ the former coach said. “I’m standing there [on the bobblehead] and I’ve got a duck in my hand that he’s just given me, that he’s retrieved, and he’s sitting by my side.”

For fans of the Vikings that might be a treasured collectible, but the chance to rummage around through the Hall of Fame coach’s garage one last time is the real prize.

Bud Grant gearing up for his final garage sale, with bobbleheads

Posted by Darin Gantt on April 21, 2017

Former Vikings coach Bud Grant’s garage sales have become almost as famous as his coaching career.

But about to turn 90, Grant said the one coming up next month will be his last. The reason why is as pragmatic as Grant himself.

“I’m running out of stuff,” he said, via Chris Tomasson of the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

For years he’s sold hunting and fishing gear and Vikings and NFL memorabilia from his Bloomington home, refusing to haggle over prices and offering whoever wanders up a chance to go through his stuff.

But picked-through as his collection might be, he’ll have a new item this year — a custom bobblehead doll.

“They’ve been after me for a bobblehead doll for years, and I just never felt the need to do that,’’ Grant said. “It’s an ego-trip kind of thing. But somebody suggested to have them at your garage sale to advertise. You’ve got to have a hook.

“You can’t just say, ‘Come to my garage sale and buy baby clothes.’ ’’

The bobblehead features Grant alongside his late hunting dog Boom, who died last October after a bout with cancer.

“I loved him dearly,’’ the former coach said. “I’m standing there [on the bobblehead] and I’ve got a duck in my hand that he’s just given me, that he’s retrieved, and he’s sitting by my side.”

For fans of the Vikings that might be a treasured collectible, but the chance to rummage around through the Hall of Fame coach’s garage one last time is the real prize.

- Thread Starter Thread Starter

- #39

http://www.espn.com/blog/nfcnorth/p...s-garage-sale-bobbleheads-are-sold-in-seconds

At Bud Grant's garage sale, bobbleheads are sold in seconds

Ben Goessling/ESPN Staff Writer

Ben Goessling/ESPN.com

BLOOMINGTON, Minn. -- Black Friday came to the Twin Cities on a Wednesday in May. The reason? Bud Grant now has a bobblehead.

Seconds after the Hall of Fame Minnesota Vikings coach opened his 13th garage sale Wednesday evening with a whistle blast, fans sprinted to a table and made like power forwards, elbowing each other out of the way for a chance at one of the 15 autographed bobbleheads Grant had on sale for the price of $150.

The coach will have another 20 on sale Thursday morning, distributing numbers to the first fans who arrive and indicate they want one. Otherwise, interested buyers will have to stop at the table in Grant's driveway, place an order and wait for the collectible to arrive in August.

Grant, who turns 90 on Saturday, welcomed fans to his driveway Wednesday evening in what has become an annual pilgrimage for those who remember the four Super Bowl teams Grant coached during his 18 seasons with the Vikings. Grant, an avid outdoorsman who has parted with hunting and fishing gear in addition to sports memorabilia over the years, had resisted overtures to sell his likeness in collectible form but decided to have the bobbleheads made for his 2017 garage sale.

The item features Grant in a Vikings jacket and headset, holding a duck and standing next to his hunting dog, Boom, a black Labrador that Grant had to put down last fall.

"He was 10 years old," Grant said. "We had a great half of last fall. He hunted with me until the middle of October, and then he got cancerous, and I had to put him down. Very sad day. But this is kind of in memory of Boom, too."

Greg Litchy, a Vikings fan from St. Cloud, Minnesota, who now lives in Largo, Florida, boarded a flight in Tampa at 6:20 Wednesday morning, arriving in the Twin Cities at 10:30 a.m. He arrived at Grant's house at 11, six hours before the start of the sale, and spent the time scouting out where the bobbleheads would be in the driveway.

Grant, Litchy said, initially wanted the bobblehead to depict him with a rifle in his hand, but he opted for a duck after the NFL said no to the gun. "As Bud put it, 'They're big-city people -- they think it'd be like a pistol,' when instead, it's a hunting rifle," Litchy said. "But it looks cool."

He had a French dip sandwich delivered to the edge of Grant's driveway from the steakhouse owned by former Minnesota North stars general manager Lou Nanne.

"As I was standing at the table, there was a whole bunch of pressure on my back," Litchy said. "But what are you going to do? It was fun. It was an adventure."

In addition to the bobbleheads, Grant debuted several items he had taken on consignment, such as a Vikings roadster selling for $9,500 and a speedboat painted like a Viking longship for $40,000.

The coach has said this year's garage sale will be his last -- a refrain he has repeated each year since the sale's popularity spiked in 2014 -- but seemed to be leaving the door open Wednesday night for another installment in 2018.

"At my age, it might be [the last one]," he said with a laugh. "But I never say never."

At Bud Grant's garage sale, bobbleheads are sold in seconds

Ben Goessling/ESPN Staff Writer

Ben Goessling/ESPN.com

BLOOMINGTON, Minn. -- Black Friday came to the Twin Cities on a Wednesday in May. The reason? Bud Grant now has a bobblehead.

Seconds after the Hall of Fame Minnesota Vikings coach opened his 13th garage sale Wednesday evening with a whistle blast, fans sprinted to a table and made like power forwards, elbowing each other out of the way for a chance at one of the 15 autographed bobbleheads Grant had on sale for the price of $150.

The coach will have another 20 on sale Thursday morning, distributing numbers to the first fans who arrive and indicate they want one. Otherwise, interested buyers will have to stop at the table in Grant's driveway, place an order and wait for the collectible to arrive in August.

Grant, who turns 90 on Saturday, welcomed fans to his driveway Wednesday evening in what has become an annual pilgrimage for those who remember the four Super Bowl teams Grant coached during his 18 seasons with the Vikings. Grant, an avid outdoorsman who has parted with hunting and fishing gear in addition to sports memorabilia over the years, had resisted overtures to sell his likeness in collectible form but decided to have the bobbleheads made for his 2017 garage sale.

The item features Grant in a Vikings jacket and headset, holding a duck and standing next to his hunting dog, Boom, a black Labrador that Grant had to put down last fall.

"He was 10 years old," Grant said. "We had a great half of last fall. He hunted with me until the middle of October, and then he got cancerous, and I had to put him down. Very sad day. But this is kind of in memory of Boom, too."

Greg Litchy, a Vikings fan from St. Cloud, Minnesota, who now lives in Largo, Florida, boarded a flight in Tampa at 6:20 Wednesday morning, arriving in the Twin Cities at 10:30 a.m. He arrived at Grant's house at 11, six hours before the start of the sale, and spent the time scouting out where the bobbleheads would be in the driveway.

Grant, Litchy said, initially wanted the bobblehead to depict him with a rifle in his hand, but he opted for a duck after the NFL said no to the gun. "As Bud put it, 'They're big-city people -- they think it'd be like a pistol,' when instead, it's a hunting rifle," Litchy said. "But it looks cool."

He had a French dip sandwich delivered to the edge of Grant's driveway from the steakhouse owned by former Minnesota North stars general manager Lou Nanne.

"As I was standing at the table, there was a whole bunch of pressure on my back," Litchy said. "But what are you going to do? It was fun. It was an adventure."

In addition to the bobbleheads, Grant debuted several items he had taken on consignment, such as a Vikings roadster selling for $9,500 and a speedboat painted like a Viking longship for $40,000.

The coach has said this year's garage sale will be his last -- a refrain he has repeated each year since the sale's popularity spiked in 2014 -- but seemed to be leaving the door open Wednesday night for another installment in 2018.

"At my age, it might be [the last one]," he said with a laugh. "But I never say never."

Classic Rams

Hall of Fame

The frustrating thing about losing to the Vikings and Cowboys in the playoffs is that the Rams were good enough to beat them. Not just saying, doing!

As consolation, I took particular glee in seeing the Raiders whip their asses in that Super Bowl. The year after that, I was still upset at the Mud Bowl loss so I skipped the NFC championship but was glad that the Vikings lost it, and that they don't have any trophy to show for getting past the Rams in the post season. Their luck ran out a week too late.

As consolation, I took particular glee in seeing the Raiders whip their asses in that Super Bowl. The year after that, I was still upset at the Mud Bowl loss so I skipped the NFC championship but was glad that the Vikings lost it, and that they don't have any trophy to show for getting past the Rams in the post season. Their luck ran out a week too late.