- Joined

- Feb 9, 2014

- Messages

- 20,922

- Name

- Peter

This is an extremely long article on what life is like in the NFL from the viewpoint of one player. So brew a pot of coffee or get a six-pack of beer and enjoy.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Nate Jackson (born June 4, 1979) is a writer and former American football tight end. He was signed by the San Francisco 49ersas an undrafted free agent in 2002 and went on to play six seasons for the Denver Broncos. LINK

http://deadspin.com/my-injury-file-how-i-shot-smoked-and-screwed-my-way-1482106392

My Injury File: How I Shot, Smoked, And Screwed My Way Through The NFL

By Nate Jackson

Slow Getting Up: A Story of NFL Survival from the Bottom of the Pile

Amazon.com

After the last game of every season, we came into work for an exit physical. I sat down in front of the team doctors and our trainer, Greek, and went over my injuries for the year—anything that required treatment during the course of the season. It could be a minor training-camp injury or a season-ender. We discussed them all. They needed to document everything because some day some of us would file worker's-compensation claims, and the Broncos would pay out the settlements.

Well, not the Broncos, but their insurance company. And the insurer has lawyers who will use these documents to build a case against me. My lawyer will defend my claims. Neutral doctors will assess my body: physicals, neurological exams, MRIs, X-rays, psychotherapists, sleep-doctors, all of it. Then a judge will decide what I deserve. These documents, which at the time I thought were necessary for the team and its medical crew to better understand my body, were really for legal purposes.

"How's your left ankle?"

"Good."

"How about your right wrist?"

"Fine."

"Right shoulder?

"Fine."

"Do you consider yourself fit to play football?"

"Yes."

"Then sign here. And have a good off-season, Nate."

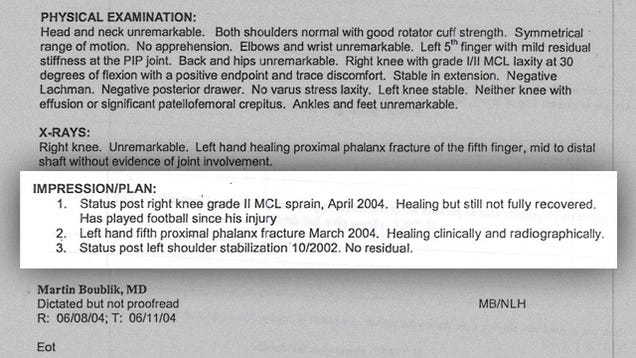

I was signing an affirmation of health. Next to that piece of paper was a file as large as a dictionary that contained my injury history. Every injury I ever had was described somewhere in that file. But I never saw it. It wasn't my property.

Had I owned that file, that information, I would have had a better idea of what was happening to me. Every treatment was in there. Every report written up by Greek or our team doctors. The results of every physical. And an unbiased report from the off-site imaging center that conducted our post-injury MRIs. These MRI reports contain information of great value to a player, because they are unfiltered. But I never saw the file. As far as I knew, I never even had access to it.

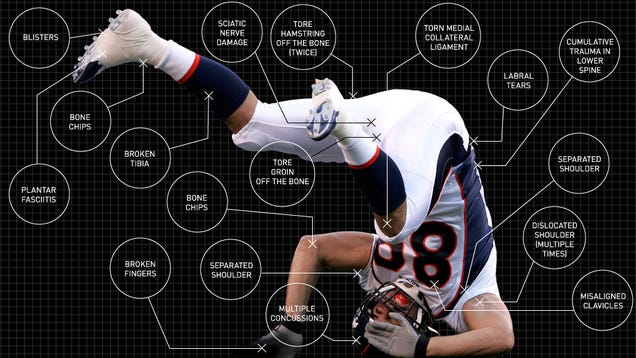

During my football career, I dislocated my shoulder multiple times, separated both shoulders, broke my tibia, broke a rib, broke my fingers, tore my medial collateral ligament in my right knee, tore my groin off the bone, tore my hamstring off the bone twice. I had bone chips in my elbow, bone chips in my ankle, concussions, sub-concussions, countless muscle strains, labral tears in either hip, cumulative trauma in the lower spine, sciatic nerve damage, achilles tendinitis, plantar fasciitis in both feet, blisters—oh the blisters! My neck is bad. My clavicles are misaligned. I probably have brain damage.

Looking at the injuries individually, it seems easy enough to diagnose and treat each one. Your groin is torn. Look up "torn groin" in the index, find the list of exercises to plug into your daily rehab regimen, and you're off and running. But seen from a distance, the litany above tells me something different. The injuries are all connected. One injury leads to the next, to the next, to the next. The aggressive rehabilitation of one muscle neglects its opposite. The body is thrown out of balance.

I now own a copy of my injury file, obtained by subpoena from the Broncos for my worker's-compensation case. Page by page I've gone through it, reminded of injuries and treatments I had forgotten. An oblique injury, a wrist injury, an ankle injury, chronic plantar fasciitis treatments, shoulder treatments, chronic hamstring issues, achilles tendon pain, groin treatments, pectoral strains, lower back pain. The list is long, the memories vivid. Four years after leaving the NFL, the story of my own body belongs to me.

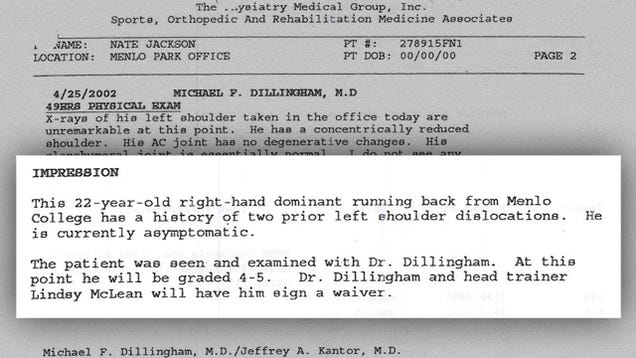

In college I dislocated my shoulder twice. The second dislocation came at the end of my senior year. I was advised that I needed surgery, but I opted against the knife. It's a four-month rehab, and it would've prevented me from working out for NFL teams and playing in the East-West Shrine Game, a college all-star game in San Francisco for standout seniors. I was the only Division III player selected. This was my time to prove I could play with the best in the country. So I rehabbed the shoulder aggressively, and it felt fine in the lead-up to the game in early January.

The day before we checked into the hotel for the weeklong festivities, Dave Muir and I went out on the Menlo College grass to run routes. Dave was an ex-quarterback for Washington State. He was also my coach at Menlo and a good friend.

It was a bit chilly in the early January twilight. But it was my favorite time to be outside running routes: the crisp air, the fading light, the musky smell.

"Colorado!" I yelled. Colorado is a wide-receiver route in the West Coast offense's route tree—a three-step slant, then back out to the corner.

"Set-hut!" Dave yelled. I took my three steps straight up the field, broke along the slant for three steps, then stuck my foot in the ground and accelerated back out toward the corner. Hello, hamstring. Yank. I pulled up and tried to walk it off.

"You OK?" asked Dave.

"I don't know."

The next few days during check-ins and meetings I concealed a soft limp. I couldn't tell anyone about it because I was the one Division III kid trying to prove himself against Division I talent. And the NFL scouts would be at every practice. This was no time to be hurt.

First practice, first route during one-on-ones, I ran a slant, tried to break away from the cornerback, and the thing really ripped this time. I was done for the week. My hamstring turned purple down behind the knee and there was a palpable depression in the middle of the muscle.

A few days before the game, some of us on the "West" squad went out in North Beach. I was in a fragile state of mind. I got in a drunken brawl and sliced up my hand on a tooth, I think. I don't remember much of it. I do remember several bouncers sitting on me until a cop came and handcuffed me. He put me in his car, and I watched my roommate and fellow wide receiver, Donnie O'Neal, plead for my release. It worked. The cop opened the door and uncuffed me and told me to scram.

We took team pictures the next day, and I had a black eye. A pretty bad one, too. A girl I was dating came to the hotel and applied makeup. The next day at the game, a hundred Menlo faithful came to support me, even though they knew I wasn't playing. It was supposed to be a happy day. It was brutally sad.

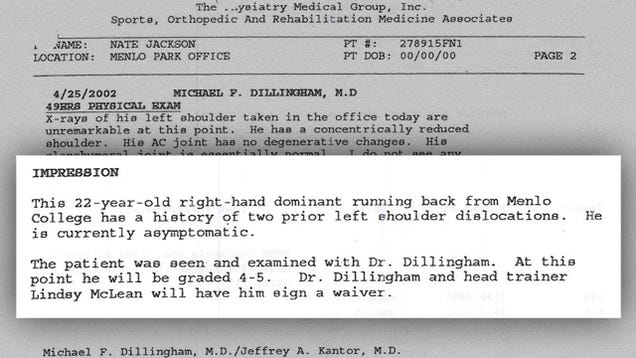

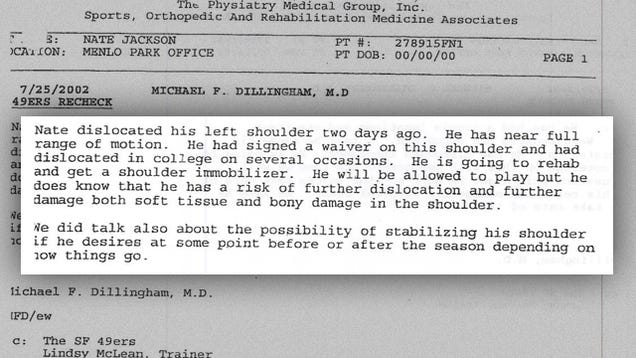

The following week, I got to work rehabbing the hamstring, which healed quickly. I was able to work out for teams and showed no residual effects from the injury. I was signed to the 49ers after the draft and passed the physical, though my bum shoulder was so unstable that they made me sign a waiver. If I didn't sign, they weren't going to let me on the field. And once I got on an NFL roster, they started documenting everything.

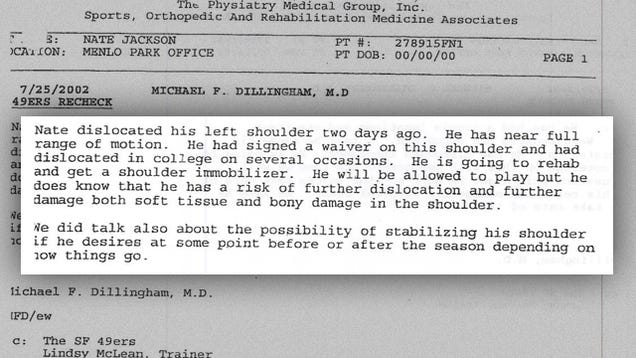

The waiver meant that if I injured the same shoulder again, they could cut me without pay or treatment. Otherwise, whenever a player is hurt, the team has to nurse him back to health. I signed the waiver and of course dislocated the shoulder again during training camp.

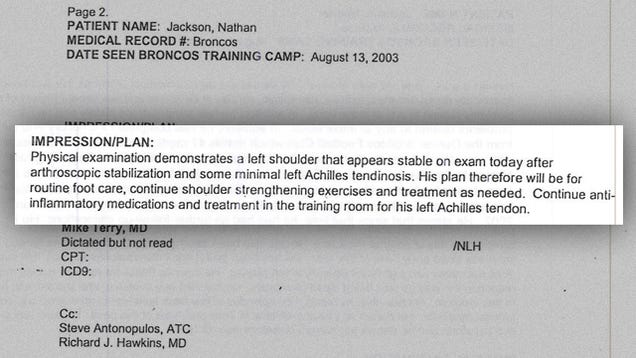

I finished camp with one good arm and was promptly cut. The next month I opted to have my left shoulder stabilized. I had surgery through my own Lifeguard insurance by a surgeon recommended by the Niners, then spent what would have been my rookie season living at home with mom and dad, staring at the walls. But my shoulder was fixed.

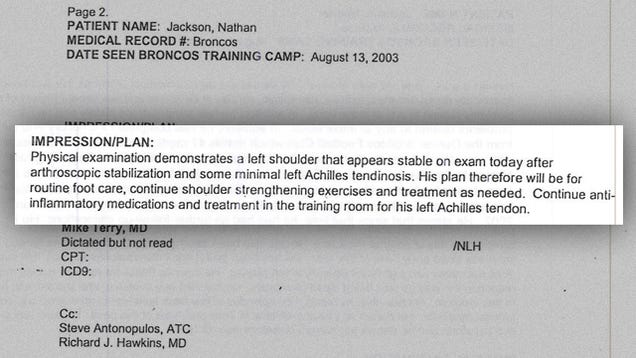

The Niners signed me back after the season. About halfway through mini-camps I developed chronic Achilles tendon pain in my left foot. My left ankle had been bad for years, and all the wear and tear was starting to affect the surrounding regions. But again, I had no time to be hurt. No football player does, especially one who's just trying to make the team. I was struggling to get reps and stuck way back on the depth chart. And you can't make the club in the tub, they say.

By then, pain had become a part of my daily life. I started to understand it, have dominion over it, control it. And this control empowered me. No matter how bad anything hurt, I could get through practice without showing it.

Halfway through training camp I was traded to the Broncos. I was the new guy again. So how's your body, Nate? It's great. Never felt better.

A few weeks later, in the last preseason game against the Seahawks, a defender landed on my outstretched arm and I felt my good shoulder sublux. I didn't say anything to the trainers about that one. Upper-body injuries are easier to play through if you can deal with the pain. It's the lower-body stuff that does you in, especially as a receiver, because you have to be able to run.

The day after making the practice squad, at our first practice of the week, I ran a route across the middle and went up high for the ball. It was a laser throw and it stuck to the hand on my new shitty shoulder. I nearly fainted it hurt so bad. I swallowed the pain and ran back to the huddle, no one the wiser. I dealt with the shoulder and the Achilles all season.

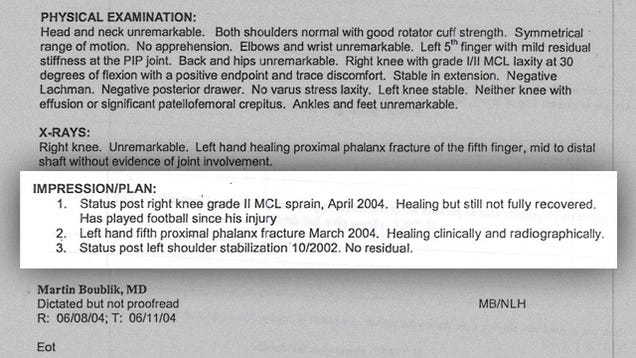

After the season, I went to NFL Europe and played for the Rhein Fire in Germany. During this three-month span, I popped a bursa sack on my left patella, broke my left pinkie, and tore my MCL in my right knee. I worked through all of these injuries, arriving back in Denver on June 7, whereupon I was deemed healthy enough to be on the field practicing the next day.

My body was tired. By this point, I'd been doing football things for 14 months straight. But I had a team to make. This training camp would be crucial for my career trajectory. Lots of guys play one year on the practice squad and that's it. Cut loose and on with life. I didn't want to be that guy.

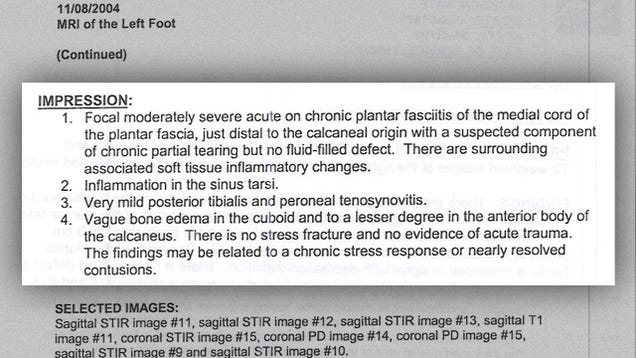

On the surface, training camp was great. I played well and made the team. But my body developed a new problem. The Achilles troubles had prompted me to re-evaluate my shoes and insoles. Perhaps I was wearing the wrong shoes. And maybe I needed lifts in the shoes to keep my heel up higher, and some soft insoles that would conform to my feet and offer better support. I tried the new foot set-up, and it alleviated some of the Achilles pain.

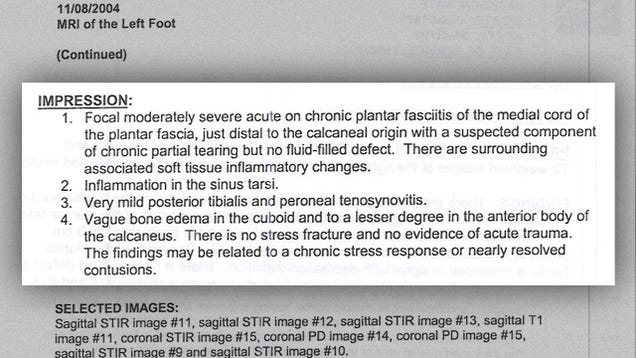

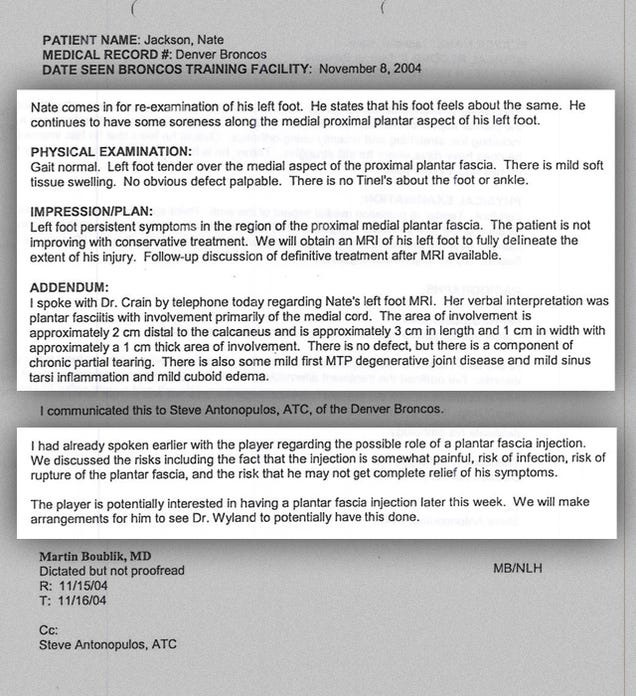

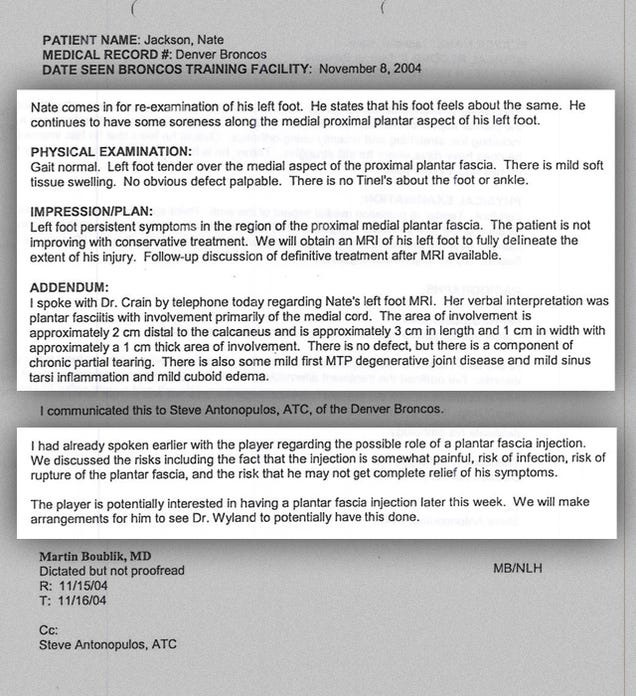

But soon the bottom of my foot began to hurt. More and more every day, the connective tissue between the heel and the ball of the foot, the fascia, became tender and painful. I had plantar fasciitis. Plantar fasciitis was similar to the Achilles pain in that it was chronic and unremitting. It hurt with every step. But after 30 minutes of practice it warmed up well enough to get through the day. Yet no treatment was helping; massage, ice, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, stretching, meds, acupuncture—nothing. The Broncos medical staff decided I needed an MRI.

I accepted the offer to inject. Thus began my long relationship with the needle-as-savior approach to injury treatment. Toradol, Bextra, Kenalog, Dexamethasone, Medrol, Cortisone, Kertax, PRP, Human Growth Hormone. The needle was the last resort when pain was too much or progress too slow.

Accompanying the injection was a new type of shoe insole: a hard, plastered orthotic. Greek imprinted my feet and sent away for it. A week later, orthotics specifically made for my feet arrived in the mail and I was told to use them in my shoes.

They put my feet at an angle that science apparently had deemed pleasing but that I found compromising. It felt as if I were standing on a pile of rocks.

"Man, Greek, these things don't feel good."

"It takes a while to get used to them, Nate. Just give it a little time."

A few weeks later we played the Chargers in San Diego. I was doing my best to work with the orthotics. The shape and size of the orthotic filled my shoes so much that it was difficult to get them on my feet comfortably. And it took a good amount of ankle tape on the outside of the shoe to secure the shoe to the foot. Once the tape was complete, I was dragging around two bricks. There was no give, no cushion, nowhere for my feet to go. I guess that was the point.

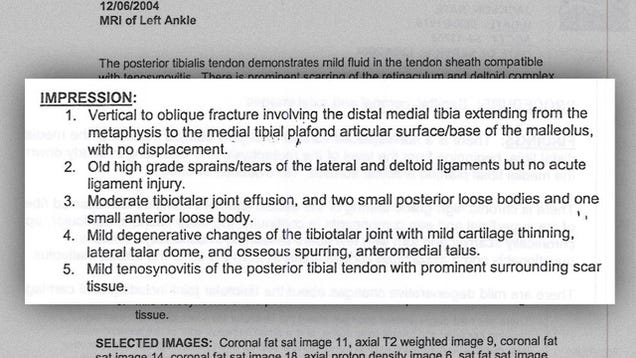

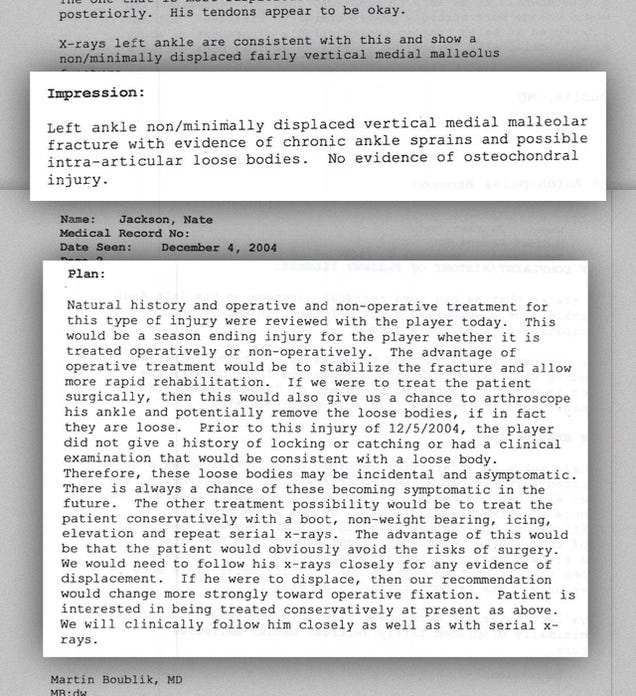

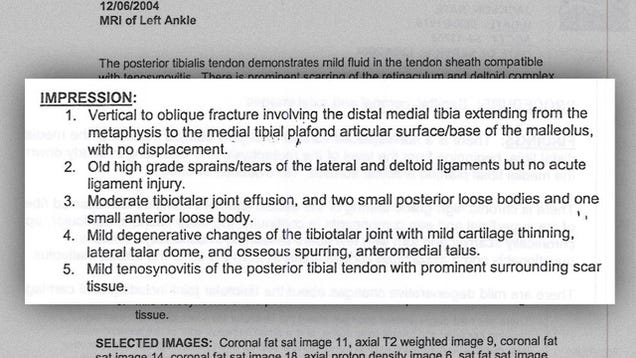

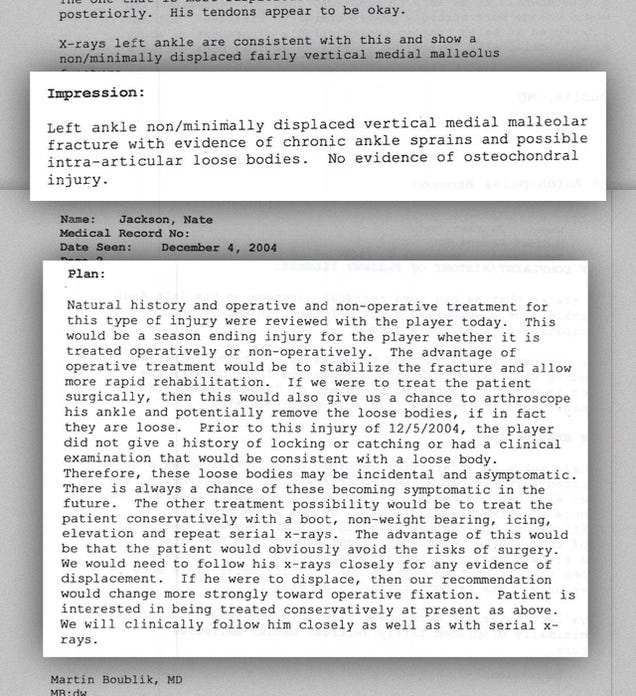

On a ball intended for me in the end zone, I got tangled up with a cornerback. He fell sideways on my left leg. Not a very hard fall. But I felt a click in my ankle. I jogged off the field and tried to walk it off. No dice. My tibia was broken—a vertical fracture through the bottom bulbous part of the bone.

My shoes and orthotics went back in the bin underneath my locker while I finished the last four games on injured reserve, and on crutches. A few months into the off-season, my rehab complete, Denver's coach, Mike Shanahan, called me with a proposition: How about tight end? He thought it would be a great way for me to get more involved with the offense and catch more passes. I agreed to the science experiment and started gaining weight that day: protein shakes, extra meals, heavier lifting.

The weight came quickly. I went from 215 to 240 in a few months, and by mini-camps I had taken on my new tight-end body. But my mind was still a wide receiver's. I ran like one and cut like one. I still knew how to move that way, and it gave me an advantage in the passing game. But my body didn't like it. The movements that I knew how to summon were being carried out by a body that was 25 pounds overweight. My pelvic girdle, the source of my torque and snap for every fast-twitch movement, was under a new kind of strain.

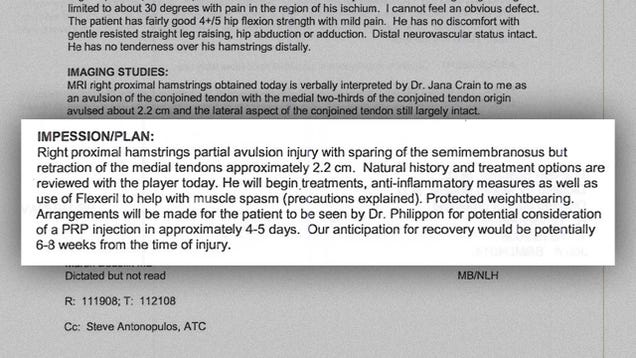

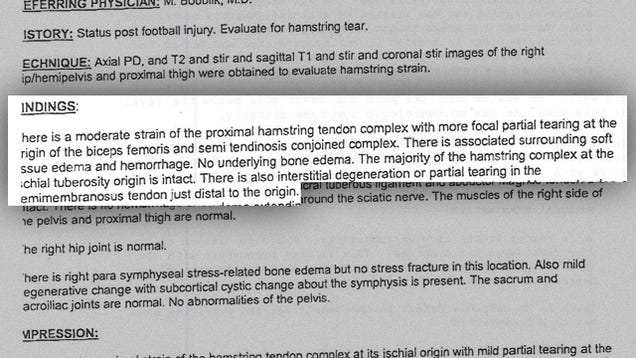

During a particularly tiresome training camp practice in early August, I ran a deep crossing route in the end zone. As I tried to accelerate past linebacker Ian Gold, he gave my jersey a small tug, and my hamstring yanked. But this time it was up high, against my butt bone. And deep, intrinsic. The rehab was ice and stim and strengthening and stretching and cardio—right away. Normal protocol. But it didn't help. After three or four days, the benchmark for noticing improvement, it was still the same. Greek was stifled.

"Feeling better today?"

"Uh, maybe a little but not really." I always said "maybe a little" even when it wasn't.

"It should be improving by now."

Twice a day I went through an extensive exercise program that targeted the injured muscle. Lots of guys get hurt in training camp. Some guys get comfortable not practicing so they're pushed back on the field, usually before they're ready. That's achieved by applying verbal pressure in the training room, creating a timeline for return, and kicking his ass in the weight room twice a day—insanely heavy lifting then 30 minutes of intense cardio—so that he'd actually prefer practice to this isolated attention.

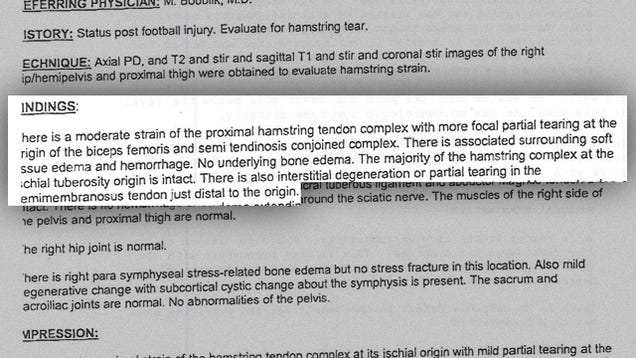

I succumbed to the pressure like everyone does and rushed myself back on the field in time to play the Houston Texans in a preseason game. During the game, I re-aggravated the injury. I don't remember how, exactly. I just overextended myself with an unhealed injury. The action on an NFL field is so fast that your subconscious takes over. If the mind is up to the task and the body is not, thwap goes the body. When we got back to Denver, I got an MRI.

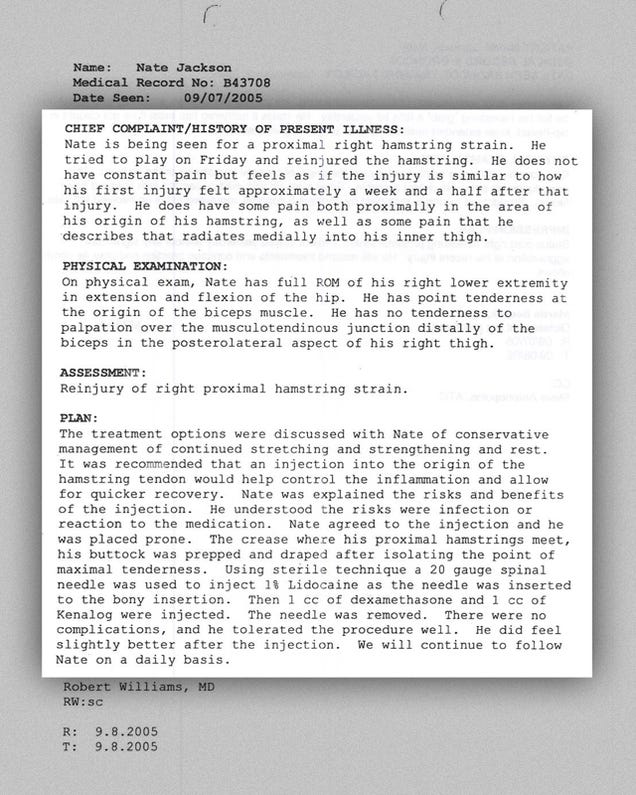

That was the report they read. The translation to me: mild hamstring strain; exercises, ice, meds, and modalities. We good, Nate?

Yeah, I guess we're good. And I was back on my daily rehab sheet. Another week and not much progress. Greek let me know in his special way that it shouldn't be taking this long to get better. In other words, my progress didn't jibe with the timeline that was laid out from the start, that fit the protocol for "mild hamstring strain." That got me thinking: What's wrong with me? Am I being a pussy or what? Greek says I should be ready to go. So I know that's what he's telling Coach Shanahan every day when he goes upstairs and gives him the injury report. Nate's milking it.

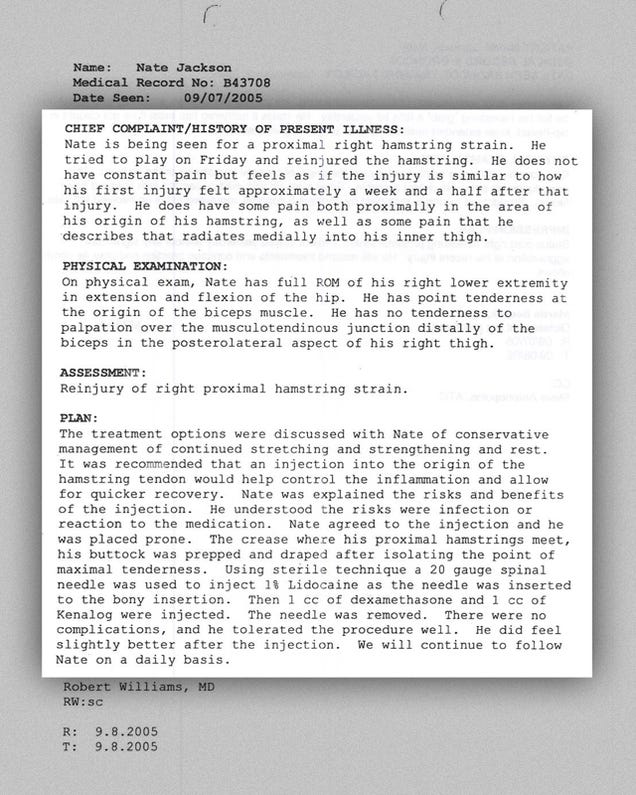

So I got myself back on the field again, in time to play another preseason game, the last of the year. I thought I needed to get on the field and prove myself a warrior if I had any chance of making the team. I got myself as ready as I could: heat, pain pills, meditation, stretching, back plaster (a patch that goes on the skin and heats up as your body warms it), and adrenaline. I played like shit anyway. And I re-injured my hamstring. Another innocuous football play; another thwap. I knew I wasn't ready, and I was right. But I made the team anyway. So the training staff decided to ramp up the treatment plan and get me back onto the field, where I could contribute to my team.

The shot got me back on the field, but my hamstring bothered me all season long. I was two steps slow. It was obvious. Watching myself on film became a painful ordeal because I looked like shit. I couldn't reach top speed, which took away my main advantage as a former receiver. The injury kept me from effectively covering kicks on special teams. All of this meant I wouldn't be getting on the field. (Bless Coach Shanahan for even keeping me on the team.) I was inactive for all but three games that season and spent the entire time trying to figure out my hamstring. Ice here, heat there, stretch here, rub there, injections, chiropractor visits, cold lasers, hot lasers, active release therapy, strength training, core work— nothing. The only thing that would help wasn't an option: rest.

But I learned to deal with the pain, the instability, the imbalance, just like every other NFL player does. My story is not unique. Every other football-playing man deals with the same cycle of injury and rehab, separated by periods of relative health. Some bodies are better suited to the demands of the game than others. They stay healthy longer, play more, smash more skulls, die younger. I should see my inability to stay healthy as a blessing in the long run, because it spared my brain the extra punishment. The fact is, no one remembers any NFL game I ever played in but me.

Exacerbating the brutal demands of the game of football is the industrial approach to training for it. In the off-season, when we might have been resting, we lifted like Olympic weightlifters. We ran like track runners. We threw enormously heavy weights around at angles that compromised our already misaligned bodies. And we did it to the steady soundtrack of "C'mon, Nate! Harder!" That's the football way. And in many ways, it's necessary. You need to be explosive and powerful to play the game at that level. But training that way has its downside. It kept me sore all year long. It also neglected the tiny, important muscles of the body to focus on the big, showy, powerlifting muscles. When those fatigued, as they always did as the practices and seasons wore on, it left the work to the smaller muscles, which were underdeveloped. The result was injury.

Now that I don't play football, I can choose what methods I use to strengthen my body. If I am hurting, I can stop. If something doesn't feel right, I don't do it. I can focus my attention on core strength instead of bench press and squats. The core is the decider and the connector. It is the source of our strength. And for the athlete, it is crucial for the transfer of power from the lower to the upper body. When the big muscles break down, the core comes to the rescue. But when I played, my core was weak, especially compared to the overdeveloped muscles on either end of my body.

But the athlete doesn't have a say in his training either. Every morning in the weight room, we picked up our personal folders. Those folders dictated the workout. We follow orders. Football players are great at that. Show up at this time. Do this. Eat this. Watch this. Take this. Wear this. Say this. Yes, sir! is the only phrase I needed to learn. And I learned it well.

Going in to the 2007 season, I was playing well and having fun. I was as healthy as I'd been in years, and I'd finally become comfortable as a tight end. Then my left groin went thwap.

I've been electrocuted once. When I was a kid there was a Coke machine in the locker room at swim practice that was busted open and the wires were hanging out. One of the kids said that if you touch that red one to that blue one, something happens. No one would do it. I was soaking wet—armor, I thought. I touched them together: THWAP! Frozen to a tuning fork of lightning bolts. Same feeling.

Chargers, Week 5. My first NFL start, two weeks after my first career touchdown. "Get yourselves warmed back up when you get back on the field," our special teams coach Scotty O. was saying. "It's getting chilly out there. You don't want to get tight!" He was offering a bit of halftime advice I wasn't listening to. I was already warmed up. I wasn't worried. Sure, there was that tiny click I felt in my left groin near the end of the first half. But I felt fine.

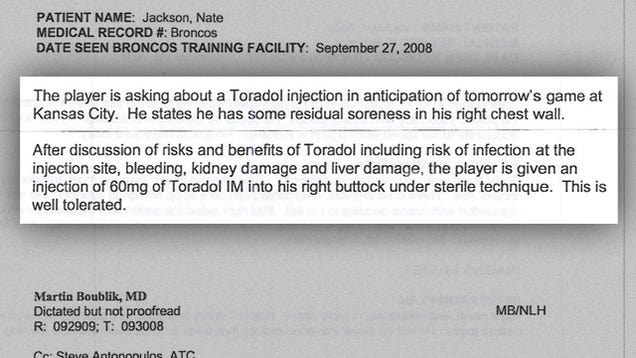

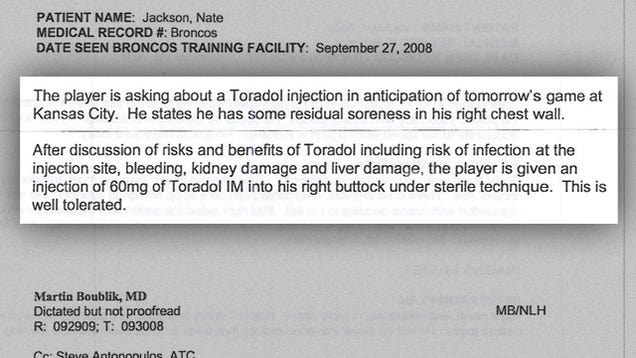

I had the needle to thank for that. After meetings the night before, I'd lined up for my shot: 60 milligrams of Toradol, a powerful anti-inflammatory and painkiller. A handful of us relied on it every game. We lived in pain during the week. We wanted relief on game day, and we didn't trust adrenaline alone to give it to us. Toradol did the trick, on the eve of the battle, so we could sleep soundly and wake up pain-free.

After jogging out of the tunnel again and drinking some sideline Gatorade, we lined up for the second-half kick-off. The ball popped off the tee and all 10 of us tore off down the field. Twenty yards into my straight-line sprint, a sniper somewhere in the cheap cheats popped one off and hit me square in the left groin, tearing the muscle off the bone with a yank that rattled the iron off of heaven's gate. THWAP!

The pop splayed my left leg off to the side. I reached for my groin and hopped on one foot. Total malfunction, but I was still on the field in the middle of the play. And I still had a job to do. The returner broke a tackle and ran through the wedge, coming right at me. I'd have to make this tackle regardless. There are things on the line, after all: pride, glory, other stuff. Hopping along like that on the 50-yard-line, some things get put in perspective. One, Scotty O. was right; I should have warmed back up. Two, I'm fucked. Three, somebody please tackle this man.

Just then a teammate tripped up the returner, and he came to rest five yards in front of me. I turned and limped to our sideline. As I reached the chalk, I got dizzy and almost fainted. My vision blurred, tunneled, then steadied again.

"What happened?" asked Greek.

"Something popped."

"Where?"

"Here." I pointed to my groin.

"OK, give it a minute and see how it feels."

"Alright." I turned my back to Greek and walked away gingerly. I knew I was done for.

I spent the rest of the game on the sideline with an ice bag stuck down my crotch. After the game I went home with instructions to return first thing in the morning to evaluate the injury. A pulled groin, they thought. No biggie. My sister Carol and brother-in-law Jeff were in town for the game. We went out to dinner, a Brazilian meat-on-a-stick restaurant downtown. I limped and hopped between the tables and chairs. People looked at me strangely. I was also meat on a stick.

The next morning I limped and hopped into the facility. My upper-inner thigh and pubic region had swelled up. I was walking timidly, slowly, straight-leggedly. Week 5 and I was crippled.

Injury treatment in the NFL, and in all levels of football, follows a certain protocol. Page one of the trainer's manual is ice and electrical stimulation, or "stim." Ice and stim; ice and stim; ice and stim. The stim uses electrical charges that pulse through two positive and two negative wire lines, like jumper cables, and are fixed to conductive pads and stuck on the skin, forming a picture frame around the injured area. The machine is turned on and electricity surges diagonally through the meat, stimulating the healing process. The muscle jumps as the electricity flows.

On top of the electrical pads, a bag of ice is fixed—form fitting and expertly tied. But it ain't just a bag of ice. There is an art to tying a bag of ice. All of the air must be sucked out of the bag before it can be twisted and tied: air tight. And it can't be ice cubes. They don't conform to the contours of the skin. It needs to be ice pebbles, ice chips, ice dust, stuff that will wrap around the injured area and freeze the muscle into a submissive post-injury state. That stops the swelling by slowing the blood flow, thus—stay with me here—speeding up the healing process.

The combination of an electric surge pulsing through the body, intended to stimulate blood flow, and an all-encompassing ice bag, intended to slow down the blood flow, might seem contradictory to someone in a position to consider it. But I was not in a position to consider it.

What's that, Nate? You want to rest it? Wait until it feels better before you start working it? No thingamajigs? Ha! You don't know anything about the human body, do you? We have to speed up the healing process! Your body's natural reaction to the injury is incorrect. We can't trust it, Nate. We need to manipulate the body's natural healing process, send shocks to it, changes of temperature, strain it to the point of exhaustion, stretch it to the point of snapping, blast it with powerful anti-inflammatories and painkillers, then shock/temperature change again, strain/stretch again, pills again, and repeat. That's how you heal the human body, Nate. Make sense?

Ice and stim, an MRI, back to the facility for more ice and stim. The training room has a sterilized smell to it: salves and creams and freshly laundered towels and cleaning supplies. I hated it, if only because I knew what the smell meant: I was injured again.

I lay on the table in the back corner sulking with an ice pack wedged in my taint, electrodes pumping diagonally through my testicles, an electric chair for my spermatazoa. I was waiting for our team doctor to arrive and assess the situation. Once the MRI results are received, the doctor meets with the athletic trainer. They discuss the findings, come up with a course of treatment, and then they brief the head coach. Once everyone is on the same page, the player is notified. Make sense?

Dr. Schlegel, one of our two team doctors, walked out of Greek's office and came to my table with an excellent poker face. "What's the word, Doc?"

"Well," he said, "there are three muscles in the groin that come up and attach to the pelvis. The MRI showed that you tore two of them off the bone. The longus and the brevis. There's a five-centimeter retraction on those muscles, meaning they tore away and retracted from the bone by five-centimeters. That's a significant retraction, but there is still one muscle intact and there are some fibers from the torn muscles that are connected to the pelvis, along with the intact muscle. Despite all of that, we feel that we'll be able to avoid surgery."

"OK."

"But this is a significant injury, Nate. We're going to give it a few days to let the swelling go down, and reassess this. But we think we're going to send you to Vail for a procedure that we've had a lot of success with lately. Greek will tell you more about it, but its an injection that uses your own blood to help speed up the healing process. Its called a platelet-rich-plasma injection. It has proven to be a very effective treatment, especially with athletes. But this is at least an 8- to 10-week recovery."

"Alright. Thanks, doc."

"No problem. And get some rest."

Doc left and I stayed. Greek came out and asked me if I had any questions about what Dr. Schlegel had told me.

"No, not really. He said I might be going to Vail. And he said I'm done for two or three months. And he said to get some rest."

"Yep, exactly. Now let's get another round of ice and stim going."

The next morning I came into the training room on crutches with a watermelon next to my DNA rifle. The swelling had overtaken my genitalia, mushing them into the opposite corner of my crotch. Black and blue ribbons curled up and down my inner thigh. A mile's worth of chains were wrapped around my pelvis, intertwined, cinched tight and locked. I was worthless. The medical staff reached the same conclusion: No point rushing it. Greek told me I was going on injured reserve. My season was over.

What do you call a football player who's not playing football? You don't.

That morning we watched special-teams film and I saw my injury on the big screen. There I was running down the field. It was me—yes, it was me. But it didn't feel as if I was watching me. I was watching someone else, some thing else. I was watching a video game. And when the video-game player hitched and started hopping, I thought, what the fuck is wrong with that guy? Fucking run! Run, you idiot!

After crutching in and out of a few meetings that day, I realized that there was no reason to be there. I was on injured reserve. I wasn't going to play. No need preparing like it. Besides, a cripple hobbling in and out of meetings every day is not a welcome sight for those trying to focus on the task at hand. A cripple makes them confront the obvious: You're one play away from looking like this.

As I lay incapacitated on the back table the next morning, my coaches came in to pay their final respects. They told me to hang in there; work hard on my rehab and I'd be as good as new. They used hushed voices and somber tones. Grave looks on their faces. l knew the score: This was my eulogy. They were moving on in order to save themselves. They had no choice. I was dead until April.

The limp and the hop: perfected in silent corridors, echoing off the tiles of an empty shower room. The watermelon ripened in the corner of my manhood. After four of five days, the swelling went down enough for me to go to Vail for the PRP injection. In the middle of the week, my girlfriend drove us up into the mountains while I squirmed in the seat like a thing unhinged.

The procedure was set for the first thing in the morning. We went up the night before and checked in to the Sonnenalp resort, dimed by the Broncos. It was just down the street from the highly esteemed Steadman-Hawkins medical clinic in the heart of beautiful Vail. A great place to convalesce. I hadn't seen my girlfriend for a while. And it was nice to get out of my house in Denver. The room at the Sonnenalp was nice too. It had a mountain lodge feel, very spacious and very cozy. We had a fireplace and a big bath tub and despite my disability, I was determined to take advantage of the accommodations.

As I lay on the bed, and as she scuttled around me rearranging things, I grabbed her and pulled her on top of me. I kissed her and reached between her legs. She protested the advance, perhaps simply to spare me the embarrassment. But I persisted, watermelon or no. She was the most beautiful creature I knew.

Delicately we removed our clothing. She maneuvered herself on top of me, flinching only slightly when she saw the rotten fruit. But her touch sparked a miraculous blood flow. In defiance of the forces that opposed it, my soldier rose to salute its muse. And in appreciation of the gesture, she gently accepted.

Slowly we squirmed, but I was wilting. I reminded myself of the objective—coming—and tried to clear my head. The miseries of life's worst moments, its deepest pains and its saddest days of bed-ridden depression, are no match for an orgasm. But the real action of the fuck—the body-on-body, the thrust-and-the-cushion, the bumping-and-pressing—was impossible to achieve.

Or was it? My will led the way, and we found the elusive rhythm. Her skin flushed; her hair follicles domed; her lips reddened. The metaphors jumbled. A spark ignited in the depths of her ocean. Faint, then less faint, creeping toward us cautiously, the tide unlocked the gates of her hibernating libido. I paddled out to meet her. In slow motion and clothed in wind-blown linens, we splashed into each other's arms as the symphony reached its crescendo. Just when the final note was to be carried into eternity, the conductor dropped his baton, and the instruments crashed to the ground, and a solitary oboe pushed out one flitting note. Poof: a puff of smoke.

"Did you?"

"I think so."

Watermelon seeds.

The next morning I crutched into the Steadman-Hawkins clinic in Vail for my PRP injection. They gave me a hospital gown and I crawled onto my gurney. Of course my nurse was pretty. This pattern developed around every genital-area injury I had during my career. The more intrusive and emasculating the treatment, the more attractive the woman who treated it.

She tied up my arm and pushed in the needle. They needed a good deal of blood for the procedure. One vial, two vial, three vials, four. I lost count. Many vials later, she pulled the needle out from under a cotton swab, pressing down and covering it quickly with a Scooby-Doo bandage.

She left the room with the vials and came came back with the blood in a bag. She opened a large circular machine and fixed the bag inside, closed the top, and turned it on. It was a centrifuge, and as it started to hum and spin, the properties of the blood began to separate into little bags on the sides of the machine

"See that one there?" she said, "the one that looks like urine? We don't need that. But see the dark, thick red stuff? That's the good stuff. Look at that. That's beautiful." She fingered the bag. "That's the platelet-rich plasma. That's what's going back inside you." She pointed to my balls.

After 30 minutes, the machine clicked off and the separation was complete. She took all of the bags and left me on my gurney to count the holes in the particle-board ceiling squares, wondering how easy it would be to pop one of them off and climb through the ventilation ducts like Bruce Willis in Die Hard. SHOOT ZE GLASS!

After a few hours of waiting, it was time for the shot. They would sedate me, my nurse said, because of the location of the injury. It would be too discomfiting otherwise. For both of us, I assumed. They wheeled me into an operating room and I looked around frightened. All of these people in masks. Why so many people? And why the masks? I'm not wearing a mask! Where's my mask? And it's so cold in here. Why so cold?

The anesthesiologist introduced himself and pushed a needle into my hand in one motion. My nurse pulled up my gown and swabbed my groin with alcohol. Can she see my penis? Nurses have kind eyes. I felt the drugs hit my blood, tubing through my veins and arteries. At the same time, I felt a trickle of alcohol catch momentum, run down a ridge, and hit the tree line in the crease between my leg and my crotch. The race was on. My eyesight fogged over. My lips felt big. It wasn't cold anymore, except for the river below, raging toward a protected marsh. My nurse watched over me maternally. I closed my eyes and surrendered to the drugs.

In the hallway on the way to the recovery room, I met Dr. Marc Philippon, PRP injector, world-renowned hip surgeon, excellent human. He was still masked and wore a full blue hospital suit. He struck a vibrant image in my loopy mind, what with his bright blue eyes and his blond hair flowing from underneath his light-blue skull cap.

"Everything went great, Nate. Really great. You'll be fine in three weeks. Now rest up, he said. All you can do is rest."

"Will you tell that to Greek?" I mumbled.

"Sure, of course," he chuckled. And he was off down the hall, wingtips echoing off the linoleum floor, blond hair bouncing to the beat.

I was back at work the next morning—strapped again to my electric chair. My only job now was rehab: At 8 a.m. I jumped on my table; at noon, I jumped off and went home. The four hours in between varied slightly from day to day, but they closely followed the protocol for a torn groin muscle, ramping up the work slightly every day, depending on my body's response.

The injected plasma encased the damaged tendons and hugged them with nutrients, forming a bridge of goop that the retracted muscles could cross before reuniting with the bone that had held it since the womb. I sat on the table and meditated through the hours of ice and stim, picturing the PRP as a fleet of noble warriors sent to save a town from a blood-thirsty regime, sort of like the Three Amigos. My torn groin was El Guapo.

Every day I went home at noon and lay on the couch. I smoked weed and thought about shit. That was it. Sit and think, and find your way to God. I found that when I ingested the team-prescribed opioid painkillers, the line to God was always busy. So I avoided them and tried to keep a clear head.

Some days I had bright ideas for home improvement. I lived alone in a big house. It was my house! I bought it! I went to Home Depot and bought every color of spray paint they had and got to work on a mural in my master bathroom. Stencils and acrylics and oils and brushes followed. The walls were my canvas. And my targets.

The next day I threw butcher knives at the walls. The one after that I strung pine cones from the rafters to usher in the snowy season. I read the first 30 pages of lots of books. But I couldn't concentrate. I took guitar lessons once a week in Boulder for a few months. That got me out of the house and gave me something productive to do. I wrote a few songs. A few poems.

The entertainment center in my living room was set into the wall about three feet deep and had a six-inch-thick dry-walled shelf built in to it that divided the top from the bottom. Sometimes I had the TV on the bottom, sometimes I moved it to the top. But I really wanted it in the middle. That fucking shelf was no good. But it was built into the damn house!

One day after rehab, I went to Home Depot and bought everything I needed to demolish it: multiple power saws, hacksaw, crowbar, sledge hammer, disc sander. I went home and tore my living room to shreds. When I finished, there was a layer of dust caked to the furniture. But the television now sat proudly in the right spot, surrounded by a torn-up wall with cables hanging out of it and exposed two-by-fours and particle board.

The injury also gave me more time to spend at home tracking the movement of the family of mice that had moved in. One night, after ingesting some unprescribed herbal medication, I was cleaning up the kitchen. I lifted a pot, and a mouse darted across the countertop. I jumped out of my slippers, hit my head on the ceiling, and moonwalked into the pantry. While I was there, I inspected the area and found a collection of turds in the corner. I wasn't surprised, as I often pooped there. But in the opposite corner of the pantry was a collection of much smaller turds: mice! The next day at rehab, I could barely contain myself. I told the story to everyone in the training room. After my workout, I went to Home Depot. By then they knew me.

"How did the demolition go?"

"Eh, ya know. Least of my worries now. I have mice."

"Mice?"

His face lit up.

"Follow me."

He took me to an aisle lined floor to ceiling with widdle fuzzy murder tools. I declined the fancier weapons and opted for the old-school hinged snap-trap. I paid for my tools and raced home. I was so excited I barely noticed my depression.

I set one trap next to the turdpile in the pantry and the rest in and around the kitchen. Then I left the house to summon the angel of death. When I walked in the front door a few hours later, a cold wind blew through me. A rodent lay dead on the kitchen floor. He'd died of a broken heart/neck. I lay another trap in the same spot, knowing his bride would come back to pay her last respects. When I woke up the next morning, the trap was gone. I found it underneath the dishwasher. Bitch got snapped and dragged herself under the dishwasher, where she wiggled free and was off in the night. Well played, Minnie. Well played.

From that day on, I sat on my kitchen counter every night with night-vision goggles on and an airsoft rifle loaded with poison-soaked pellets. I wasn't going to be made a fool of by no mouse. Eventually the snap-trap snuffed her out—THWAP!—then it got the three kids. I sealed up their entry points, which I found on either corner of the garage door. I felt triumphant in my kingdom of solitude.

But I was a living shadow outside of my house, ducking in and out so as not to be seen, not to have to speak to anyone. When I was at the facility, I was the model of hard work and enthusiasm. I pushed the limits on every exercise. "Is that all you got for me Greek? I'm feeling great!" my groin healed much quicker than expected. It healed so fast that it was still November and I felt as if I could be playing. Should be playing. I'm a football player, dammit! But that was my pride talking.

What I know now, after reading the fine print in my injury file, is that my groin absolutely was not healed. It was still torn then just like it is now. Just like it always will be.

The following season, I felt good. Things were going well again. Then I woke up one morning during training camp and I could barely walk. My ankle swelled up for no reason. No trauma. No twisting. Just a backlog of gunk. The ankle itself had a thick memory of pain that the slightest tweak would call forth. The loose bone fragments and spurs and ligament scarring and calcification of the tibia fracture made for a temperamental area on a very active region of my football body. A few days of rehab and "Feeling better yet?"s and I was back on the field, limping.

A few days later we began our preseason practices against our first opponent: the Cowboys. I was playing fullback on one particular play, as tight ends are often asked to do, and I was the lead blocker. I knew coming out of the huddle that the play was going to fall to shit. That's probably why it did. I hated getting put in at fullback. Whenever I did, I looked at my coach like, "Really?" He looked at me like, "Yeah, really, motherfucker!" I came into the league as a receiver. Now here I was in a three-point stance, lead-blocking through the two-hole, about to get my dick ripped off by a snarling linebacker.

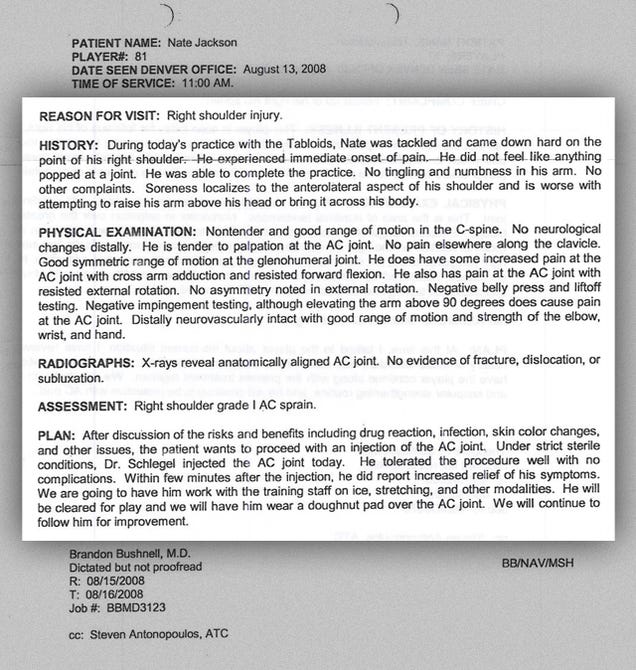

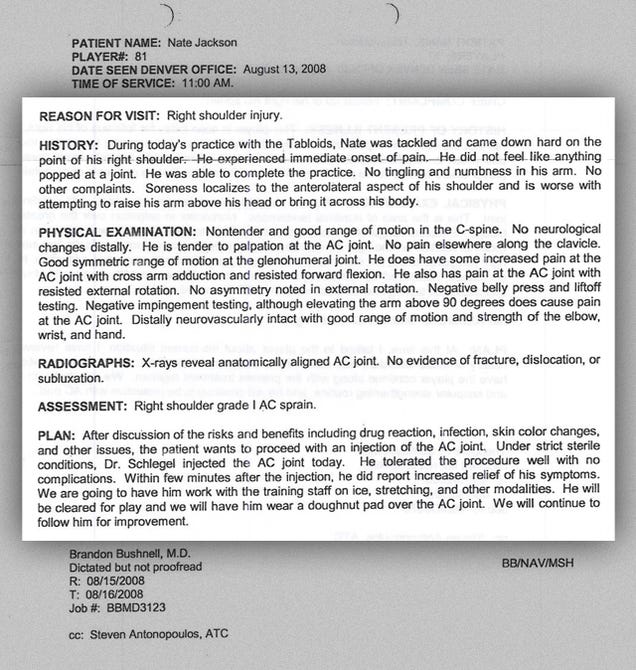

I came through the hole off-balance and met their backup middle linebacker, Bobby Carpenter, with a hearty pop, taking it all on the point of my right shoulder. I felt it buckle and separate. A power hose of fire ants shot through the right side of my body. But a shoulder separation is only pain. So deal with it. There are several treatment options. One is preferred.

Hello again, Mr. Needle, how well you mask my pain. But will I pay for this quick fix some other lonely day?

The needle worked, and I forgot about my shoulder. There were new pains to address. It seemed as if my mind never took on more pain than it could handle. An instability or a new injury might be waiting in the wings, might already be symptomatic, but it was always polite enough to wait until the previous injury had significantly improved before roaring to life. A few weeks into the season, my shoulder was an afterthought. Now I was bothered by a pectoral strain. It wasn't a big deal, and actually it gave me a "legitimate" excuse for getting an injection the night before the game. This pacified the subconscious reluctance of both doctor and patient to engage in such an overtly risky and unsound medical practice just to juice up a bit player for an early-season football game.

One week later during Friday practice, I ran a hook route and felt something yank in my right oblique area. It was toward the end of a light practice. It was diagnosed as a "right costochondral irritation at roughly the 10th rib".

The next morning we left for Kansas City. I was in a lot of pain, possibly the most painful injury I'd ever played with. Another 60 milligrams of Toradol into my ass the night before the game. Didn't help. The muscles in the torso are constantly at work while playing football. Twisting, cutting, exploding, sprinting—all of it activates the obliques. Warm-ups were so painful that I was considering the unthinkable: telling coach I couldn't play. But my pride wouldn't let me. And when one guy goes down right before the game, it throws the machine out of whack.

The coaches have to scramble to fill his spots with guys who aren't prepared to play. I was on all the special teams. I practiced all week. I knew all the plays. I had to be out there. So I was. But I was whimpering to myself the whole time. As I ran on the field before each play, I asked myself: How are you going to get through this play? And after each play, I asked myself: How are you going to get through the next one? Eventually the game was over. I think we lost. Or maybe we won. I didn't care.

More Toradol for the next week's game, and all subsequent games. And all previous games. Every game a needle.

On a Thursday night game in Cleveland a month later, I was hit in the head and neck while airborne and perpendicular to the ground. It was Willie McGinest who got me. His hit knocked me out. I was dizzy and depressed and my neck was locked for the next week. But I didn't receive any treatment for it. By then I knew the drill. Come in to work and get strapped to machines all day just so we can log it in the book. I weighed the options in my head: peace of mind or peace of nothing. I chose peace of mind and stayed at home, where I could rest and medicate myself with drugs of my choosing, drugs that didn't come out of a needle and wouldn't eat away stomach lining.

The NFL is a constant study of pain: physical and mental. How to manage the pain? It's an important question that all players must answer for themselves, and everyone has a different approach? I found marijuana worked best for me. I developed no physical dependence on it, as many of my friends did with pain pills, and it never interfered with my work. I was competing against the best athletes on the planet at the very top of my field. I wasn't a burnout stoner eating TV dinners on grandma's couch. I was alleviating a vicious physical symptom of my job, which was putting my body under constant attack. So I weeded as needed.

Another routine 60 milligrams of Toradol for the following game in Atlanta.

Usually by the time the season started, my weight would begin to drop. It was hard for me to keep on the tight-end pounds, because practices were so strenuous, my metabolism was so fast, and I was never hungry. My appetite showed itself only at night, when I was relaxed. The rest of the day I was tense and my stomach was knotted. The weight loss compromised my ability to block defensive linemen. I was getting thrown around, so every once in a while I took a scoop of creatine to help build a little muscle and put on a little weight. But the creatine dried me out. I needed to drink lots of water to avoid cramps and muscle pulls. But I preferred that to getting my ass kicked every day.

A few days after the Falcons game, we were practicing for the Raiders. It was a day just like all the rest. Practice was dragging along. There were two tight ends in the huddle: me and Tony Scheffler. The play called for us to do mirrored corner routes on either side of the ball. Tony and I were always being scolded for not reaching our required depth on our routes. If the route called for 10 yards, we broke it off at nine. If it called for 12, we made it 11. We were very similar route runners—eager to get there and eager to get the ball. As the huddle broke, we agreed. "Let's see who can get their full 10 yards on this one!"

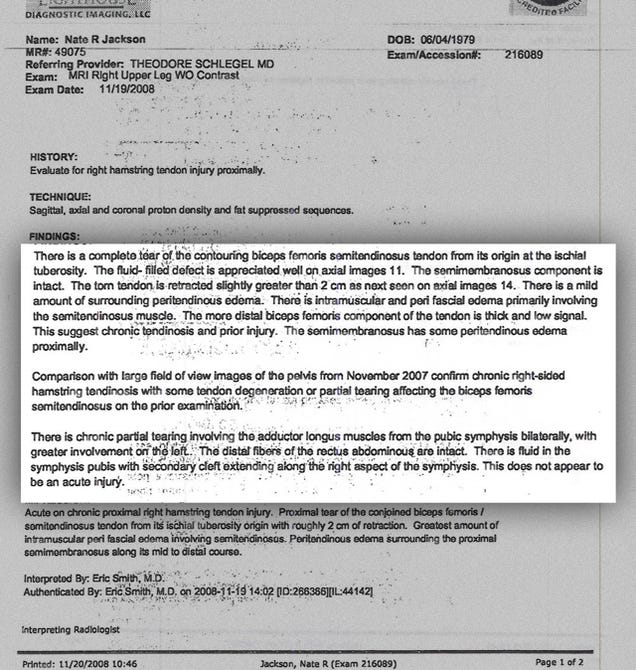

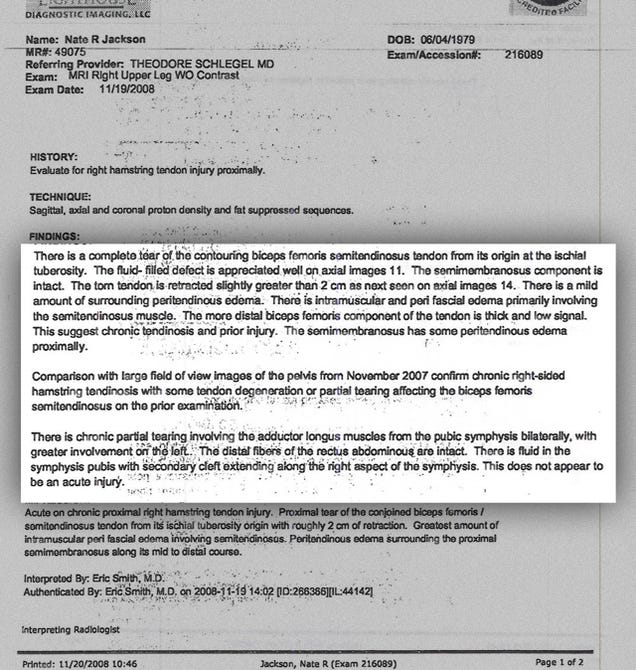

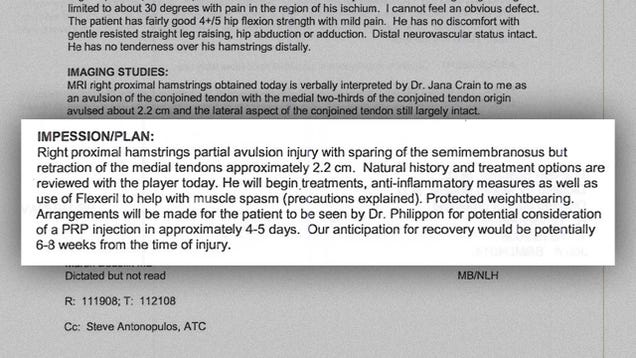

I ran my route to the full 10 and broke to the corner. The ball was thrown to me. I accelerated to track it down. THWAP! Right hamstring, again. Season over, again. Career soon to follow. The Lighthouse Diagnostic Imaging Center reported its findings:

Not an acute injury. Both groins already torn. Both hamstrings already torn. Both hips already torn. The hamstring that had bothered me for years was torn from its attachment the whole time. It never healed from the rehab or the injection or the off-season. It was ready to blow at any moment.

The PRP injection didn't have the same effect this time around. My hamstring never healed from that tear. How could it heal, anyway? Looking back at all the MRI results and the treatments and the injections and the meds, coupled with the constant demands of high-paced, physically explosive performance, there was no way it could heal. I was constantly hanging on by a thread. That's how it felt because that's how it was. Only now do I understand that my pains weren't phantom pains. It wasn't me being a pussy. My body was a mess.

But what was the main culprit? The Toradol shots? All the anti-inflammatories and painkillers? My diet? Was it the creatine? Poor treatments of my chronic hamstring injury? Poor health care in general? The steroid injection in the ischial tuberosity two years earlier? Was it the hamstring overcompensating for a weak groin? My weight gain? A weak core? Fatigue? Was it my mind? Was it fate? God? No. None of it. It was football. I played football for a living. THWAP!

What followed was an exercise in desperation—a case study in the slow-burn realization of the bitter end. Soon the season ended and Coach Shanahan was fired. Josh McDaniels was hired, and he cut me along with seemingly a third of the roster. I was without a team for the time in years, but I had plenty of football left in me. At least, that's what I told myself. But my hamstring was shit. The PRP shot didn't work this time. I figured I'd have to do something about that. That something was another needle, this one filled with a banned substance.

I acquired some Human Growth Hormone from Mexico and started injecting myself immediately. I knew all about HGH thanks to the media. A moral panic is the best marketing for an illicit drug. The media told me HGH would fix all my problems. They said that the NFL should test for it lest it give anyone an unfair advantage, though they also said everyone was on the stuff anyway. But the NFL didn't test for it. And I was a broken machine. This was my only chance, I thought.

I spent the next five months in San Diego, shooting up and working out. I expected a transformation. I expected a miracle. All I got was an achy body and some well-developed muscles that more effectively concealed a hamstring that was torn off the bone. I had workouts in Philadelphia, New Orleans, Cleveland. I was signed to the Browns then cut one week later. The NFL season started the next week, and I was jobless, so I packed my car up and drove to Arizona as a member of the Las Vegas Locomotives. They'd drafted me at the beginning of the summer and still held my rights. I signed a $35,000 and went back to training camp.

Two weeks into camp, I was running a corner route during one-on-ones. I had my man beat clean and caught a perfectly thrown deep ball. Touchdown. Fate shook his head, took one more drag from his cigarette, leveled his rifle, steadied his hand, and fired. No doubts this time. The sniper had hit his mark. THWAP!

My hamstring exploded as I decelerated. I hopped twice on my opposite foot, dropped the ball to the grass, sat down next to it, and popped off my helmet. A mosquito hovered at eye level. It's over now, I thought. It's all over.

Nate Jackson played six seasons in the National Football League as a wide receiver and a tight end. His writing has appeared in Deadspin, Slate, the Daily Beast, BuzzFeed, TheWall Street Journal, and TheNew York Times. A native of San Jose, California, he now lives in Los Angeles. Slow Getting Up, from which this story was adapted, is his first book. Follow him on Twitter, @NathanSerious.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Nate Jackson (born June 4, 1979) is a writer and former American football tight end. He was signed by the San Francisco 49ersas an undrafted free agent in 2002 and went on to play six seasons for the Denver Broncos. LINK

http://deadspin.com/my-injury-file-how-i-shot-smoked-and-screwed-my-way-1482106392

My Injury File: How I Shot, Smoked, And Screwed My Way Through The NFL

By Nate Jackson

Slow Getting Up: A Story of NFL Survival from the Bottom of the Pile

Amazon.com

After the last game of every season, we came into work for an exit physical. I sat down in front of the team doctors and our trainer, Greek, and went over my injuries for the year—anything that required treatment during the course of the season. It could be a minor training-camp injury or a season-ender. We discussed them all. They needed to document everything because some day some of us would file worker's-compensation claims, and the Broncos would pay out the settlements.

Well, not the Broncos, but their insurance company. And the insurer has lawyers who will use these documents to build a case against me. My lawyer will defend my claims. Neutral doctors will assess my body: physicals, neurological exams, MRIs, X-rays, psychotherapists, sleep-doctors, all of it. Then a judge will decide what I deserve. These documents, which at the time I thought were necessary for the team and its medical crew to better understand my body, were really for legal purposes.

"How's your left ankle?"

"Good."

"How about your right wrist?"

"Fine."

"Right shoulder?

"Fine."

"Do you consider yourself fit to play football?"

"Yes."

"Then sign here. And have a good off-season, Nate."

I was signing an affirmation of health. Next to that piece of paper was a file as large as a dictionary that contained my injury history. Every injury I ever had was described somewhere in that file. But I never saw it. It wasn't my property.

Had I owned that file, that information, I would have had a better idea of what was happening to me. Every treatment was in there. Every report written up by Greek or our team doctors. The results of every physical. And an unbiased report from the off-site imaging center that conducted our post-injury MRIs. These MRI reports contain information of great value to a player, because they are unfiltered. But I never saw the file. As far as I knew, I never even had access to it.

During my football career, I dislocated my shoulder multiple times, separated both shoulders, broke my tibia, broke a rib, broke my fingers, tore my medial collateral ligament in my right knee, tore my groin off the bone, tore my hamstring off the bone twice. I had bone chips in my elbow, bone chips in my ankle, concussions, sub-concussions, countless muscle strains, labral tears in either hip, cumulative trauma in the lower spine, sciatic nerve damage, achilles tendinitis, plantar fasciitis in both feet, blisters—oh the blisters! My neck is bad. My clavicles are misaligned. I probably have brain damage.

Looking at the injuries individually, it seems easy enough to diagnose and treat each one. Your groin is torn. Look up "torn groin" in the index, find the list of exercises to plug into your daily rehab regimen, and you're off and running. But seen from a distance, the litany above tells me something different. The injuries are all connected. One injury leads to the next, to the next, to the next. The aggressive rehabilitation of one muscle neglects its opposite. The body is thrown out of balance.

I now own a copy of my injury file, obtained by subpoena from the Broncos for my worker's-compensation case. Page by page I've gone through it, reminded of injuries and treatments I had forgotten. An oblique injury, a wrist injury, an ankle injury, chronic plantar fasciitis treatments, shoulder treatments, chronic hamstring issues, achilles tendon pain, groin treatments, pectoral strains, lower back pain. The list is long, the memories vivid. Four years after leaving the NFL, the story of my own body belongs to me.

In college I dislocated my shoulder twice. The second dislocation came at the end of my senior year. I was advised that I needed surgery, but I opted against the knife. It's a four-month rehab, and it would've prevented me from working out for NFL teams and playing in the East-West Shrine Game, a college all-star game in San Francisco for standout seniors. I was the only Division III player selected. This was my time to prove I could play with the best in the country. So I rehabbed the shoulder aggressively, and it felt fine in the lead-up to the game in early January.

The day before we checked into the hotel for the weeklong festivities, Dave Muir and I went out on the Menlo College grass to run routes. Dave was an ex-quarterback for Washington State. He was also my coach at Menlo and a good friend.

It was a bit chilly in the early January twilight. But it was my favorite time to be outside running routes: the crisp air, the fading light, the musky smell.

"Colorado!" I yelled. Colorado is a wide-receiver route in the West Coast offense's route tree—a three-step slant, then back out to the corner.

"Set-hut!" Dave yelled. I took my three steps straight up the field, broke along the slant for three steps, then stuck my foot in the ground and accelerated back out toward the corner. Hello, hamstring. Yank. I pulled up and tried to walk it off.

"You OK?" asked Dave.

"I don't know."

The next few days during check-ins and meetings I concealed a soft limp. I couldn't tell anyone about it because I was the one Division III kid trying to prove himself against Division I talent. And the NFL scouts would be at every practice. This was no time to be hurt.

First practice, first route during one-on-ones, I ran a slant, tried to break away from the cornerback, and the thing really ripped this time. I was done for the week. My hamstring turned purple down behind the knee and there was a palpable depression in the middle of the muscle.

A few days before the game, some of us on the "West" squad went out in North Beach. I was in a fragile state of mind. I got in a drunken brawl and sliced up my hand on a tooth, I think. I don't remember much of it. I do remember several bouncers sitting on me until a cop came and handcuffed me. He put me in his car, and I watched my roommate and fellow wide receiver, Donnie O'Neal, plead for my release. It worked. The cop opened the door and uncuffed me and told me to scram.

We took team pictures the next day, and I had a black eye. A pretty bad one, too. A girl I was dating came to the hotel and applied makeup. The next day at the game, a hundred Menlo faithful came to support me, even though they knew I wasn't playing. It was supposed to be a happy day. It was brutally sad.

The following week, I got to work rehabbing the hamstring, which healed quickly. I was able to work out for teams and showed no residual effects from the injury. I was signed to the 49ers after the draft and passed the physical, though my bum shoulder was so unstable that they made me sign a waiver. If I didn't sign, they weren't going to let me on the field. And once I got on an NFL roster, they started documenting everything.

The waiver meant that if I injured the same shoulder again, they could cut me without pay or treatment. Otherwise, whenever a player is hurt, the team has to nurse him back to health. I signed the waiver and of course dislocated the shoulder again during training camp.

I finished camp with one good arm and was promptly cut. The next month I opted to have my left shoulder stabilized. I had surgery through my own Lifeguard insurance by a surgeon recommended by the Niners, then spent what would have been my rookie season living at home with mom and dad, staring at the walls. But my shoulder was fixed.

The Niners signed me back after the season. About halfway through mini-camps I developed chronic Achilles tendon pain in my left foot. My left ankle had been bad for years, and all the wear and tear was starting to affect the surrounding regions. But again, I had no time to be hurt. No football player does, especially one who's just trying to make the team. I was struggling to get reps and stuck way back on the depth chart. And you can't make the club in the tub, they say.

By then, pain had become a part of my daily life. I started to understand it, have dominion over it, control it. And this control empowered me. No matter how bad anything hurt, I could get through practice without showing it.

Halfway through training camp I was traded to the Broncos. I was the new guy again. So how's your body, Nate? It's great. Never felt better.

A few weeks later, in the last preseason game against the Seahawks, a defender landed on my outstretched arm and I felt my good shoulder sublux. I didn't say anything to the trainers about that one. Upper-body injuries are easier to play through if you can deal with the pain. It's the lower-body stuff that does you in, especially as a receiver, because you have to be able to run.

The day after making the practice squad, at our first practice of the week, I ran a route across the middle and went up high for the ball. It was a laser throw and it stuck to the hand on my new shitty shoulder. I nearly fainted it hurt so bad. I swallowed the pain and ran back to the huddle, no one the wiser. I dealt with the shoulder and the Achilles all season.

After the season, I went to NFL Europe and played for the Rhein Fire in Germany. During this three-month span, I popped a bursa sack on my left patella, broke my left pinkie, and tore my MCL in my right knee. I worked through all of these injuries, arriving back in Denver on June 7, whereupon I was deemed healthy enough to be on the field practicing the next day.

My body was tired. By this point, I'd been doing football things for 14 months straight. But I had a team to make. This training camp would be crucial for my career trajectory. Lots of guys play one year on the practice squad and that's it. Cut loose and on with life. I didn't want to be that guy.

On the surface, training camp was great. I played well and made the team. But my body developed a new problem. The Achilles troubles had prompted me to re-evaluate my shoes and insoles. Perhaps I was wearing the wrong shoes. And maybe I needed lifts in the shoes to keep my heel up higher, and some soft insoles that would conform to my feet and offer better support. I tried the new foot set-up, and it alleviated some of the Achilles pain.

But soon the bottom of my foot began to hurt. More and more every day, the connective tissue between the heel and the ball of the foot, the fascia, became tender and painful. I had plantar fasciitis. Plantar fasciitis was similar to the Achilles pain in that it was chronic and unremitting. It hurt with every step. But after 30 minutes of practice it warmed up well enough to get through the day. Yet no treatment was helping; massage, ice, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, stretching, meds, acupuncture—nothing. The Broncos medical staff decided I needed an MRI.

I accepted the offer to inject. Thus began my long relationship with the needle-as-savior approach to injury treatment. Toradol, Bextra, Kenalog, Dexamethasone, Medrol, Cortisone, Kertax, PRP, Human Growth Hormone. The needle was the last resort when pain was too much or progress too slow.

Accompanying the injection was a new type of shoe insole: a hard, plastered orthotic. Greek imprinted my feet and sent away for it. A week later, orthotics specifically made for my feet arrived in the mail and I was told to use them in my shoes.

They put my feet at an angle that science apparently had deemed pleasing but that I found compromising. It felt as if I were standing on a pile of rocks.

"Man, Greek, these things don't feel good."

"It takes a while to get used to them, Nate. Just give it a little time."

A few weeks later we played the Chargers in San Diego. I was doing my best to work with the orthotics. The shape and size of the orthotic filled my shoes so much that it was difficult to get them on my feet comfortably. And it took a good amount of ankle tape on the outside of the shoe to secure the shoe to the foot. Once the tape was complete, I was dragging around two bricks. There was no give, no cushion, nowhere for my feet to go. I guess that was the point.

On a ball intended for me in the end zone, I got tangled up with a cornerback. He fell sideways on my left leg. Not a very hard fall. But I felt a click in my ankle. I jogged off the field and tried to walk it off. No dice. My tibia was broken—a vertical fracture through the bottom bulbous part of the bone.

My shoes and orthotics went back in the bin underneath my locker while I finished the last four games on injured reserve, and on crutches. A few months into the off-season, my rehab complete, Denver's coach, Mike Shanahan, called me with a proposition: How about tight end? He thought it would be a great way for me to get more involved with the offense and catch more passes. I agreed to the science experiment and started gaining weight that day: protein shakes, extra meals, heavier lifting.

The weight came quickly. I went from 215 to 240 in a few months, and by mini-camps I had taken on my new tight-end body. But my mind was still a wide receiver's. I ran like one and cut like one. I still knew how to move that way, and it gave me an advantage in the passing game. But my body didn't like it. The movements that I knew how to summon were being carried out by a body that was 25 pounds overweight. My pelvic girdle, the source of my torque and snap for every fast-twitch movement, was under a new kind of strain.

During a particularly tiresome training camp practice in early August, I ran a deep crossing route in the end zone. As I tried to accelerate past linebacker Ian Gold, he gave my jersey a small tug, and my hamstring yanked. But this time it was up high, against my butt bone. And deep, intrinsic. The rehab was ice and stim and strengthening and stretching and cardio—right away. Normal protocol. But it didn't help. After three or four days, the benchmark for noticing improvement, it was still the same. Greek was stifled.

"Feeling better today?"

"Uh, maybe a little but not really." I always said "maybe a little" even when it wasn't.

"It should be improving by now."

Twice a day I went through an extensive exercise program that targeted the injured muscle. Lots of guys get hurt in training camp. Some guys get comfortable not practicing so they're pushed back on the field, usually before they're ready. That's achieved by applying verbal pressure in the training room, creating a timeline for return, and kicking his ass in the weight room twice a day—insanely heavy lifting then 30 minutes of intense cardio—so that he'd actually prefer practice to this isolated attention.

I succumbed to the pressure like everyone does and rushed myself back on the field in time to play the Houston Texans in a preseason game. During the game, I re-aggravated the injury. I don't remember how, exactly. I just overextended myself with an unhealed injury. The action on an NFL field is so fast that your subconscious takes over. If the mind is up to the task and the body is not, thwap goes the body. When we got back to Denver, I got an MRI.

That was the report they read. The translation to me: mild hamstring strain; exercises, ice, meds, and modalities. We good, Nate?

Yeah, I guess we're good. And I was back on my daily rehab sheet. Another week and not much progress. Greek let me know in his special way that it shouldn't be taking this long to get better. In other words, my progress didn't jibe with the timeline that was laid out from the start, that fit the protocol for "mild hamstring strain." That got me thinking: What's wrong with me? Am I being a pussy or what? Greek says I should be ready to go. So I know that's what he's telling Coach Shanahan every day when he goes upstairs and gives him the injury report. Nate's milking it.

So I got myself back on the field again, in time to play another preseason game, the last of the year. I thought I needed to get on the field and prove myself a warrior if I had any chance of making the team. I got myself as ready as I could: heat, pain pills, meditation, stretching, back plaster (a patch that goes on the skin and heats up as your body warms it), and adrenaline. I played like shit anyway. And I re-injured my hamstring. Another innocuous football play; another thwap. I knew I wasn't ready, and I was right. But I made the team anyway. So the training staff decided to ramp up the treatment plan and get me back onto the field, where I could contribute to my team.

The shot got me back on the field, but my hamstring bothered me all season long. I was two steps slow. It was obvious. Watching myself on film became a painful ordeal because I looked like shit. I couldn't reach top speed, which took away my main advantage as a former receiver. The injury kept me from effectively covering kicks on special teams. All of this meant I wouldn't be getting on the field. (Bless Coach Shanahan for even keeping me on the team.) I was inactive for all but three games that season and spent the entire time trying to figure out my hamstring. Ice here, heat there, stretch here, rub there, injections, chiropractor visits, cold lasers, hot lasers, active release therapy, strength training, core work— nothing. The only thing that would help wasn't an option: rest.

But I learned to deal with the pain, the instability, the imbalance, just like every other NFL player does. My story is not unique. Every other football-playing man deals with the same cycle of injury and rehab, separated by periods of relative health. Some bodies are better suited to the demands of the game than others. They stay healthy longer, play more, smash more skulls, die younger. I should see my inability to stay healthy as a blessing in the long run, because it spared my brain the extra punishment. The fact is, no one remembers any NFL game I ever played in but me.

Exacerbating the brutal demands of the game of football is the industrial approach to training for it. In the off-season, when we might have been resting, we lifted like Olympic weightlifters. We ran like track runners. We threw enormously heavy weights around at angles that compromised our already misaligned bodies. And we did it to the steady soundtrack of "C'mon, Nate! Harder!" That's the football way. And in many ways, it's necessary. You need to be explosive and powerful to play the game at that level. But training that way has its downside. It kept me sore all year long. It also neglected the tiny, important muscles of the body to focus on the big, showy, powerlifting muscles. When those fatigued, as they always did as the practices and seasons wore on, it left the work to the smaller muscles, which were underdeveloped. The result was injury.

Now that I don't play football, I can choose what methods I use to strengthen my body. If I am hurting, I can stop. If something doesn't feel right, I don't do it. I can focus my attention on core strength instead of bench press and squats. The core is the decider and the connector. It is the source of our strength. And for the athlete, it is crucial for the transfer of power from the lower to the upper body. When the big muscles break down, the core comes to the rescue. But when I played, my core was weak, especially compared to the overdeveloped muscles on either end of my body.

But the athlete doesn't have a say in his training either. Every morning in the weight room, we picked up our personal folders. Those folders dictated the workout. We follow orders. Football players are great at that. Show up at this time. Do this. Eat this. Watch this. Take this. Wear this. Say this. Yes, sir! is the only phrase I needed to learn. And I learned it well.

Going in to the 2007 season, I was playing well and having fun. I was as healthy as I'd been in years, and I'd finally become comfortable as a tight end. Then my left groin went thwap.

I've been electrocuted once. When I was a kid there was a Coke machine in the locker room at swim practice that was busted open and the wires were hanging out. One of the kids said that if you touch that red one to that blue one, something happens. No one would do it. I was soaking wet—armor, I thought. I touched them together: THWAP! Frozen to a tuning fork of lightning bolts. Same feeling.

Chargers, Week 5. My first NFL start, two weeks after my first career touchdown. "Get yourselves warmed back up when you get back on the field," our special teams coach Scotty O. was saying. "It's getting chilly out there. You don't want to get tight!" He was offering a bit of halftime advice I wasn't listening to. I was already warmed up. I wasn't worried. Sure, there was that tiny click I felt in my left groin near the end of the first half. But I felt fine.

I had the needle to thank for that. After meetings the night before, I'd lined up for my shot: 60 milligrams of Toradol, a powerful anti-inflammatory and painkiller. A handful of us relied on it every game. We lived in pain during the week. We wanted relief on game day, and we didn't trust adrenaline alone to give it to us. Toradol did the trick, on the eve of the battle, so we could sleep soundly and wake up pain-free.

After jogging out of the tunnel again and drinking some sideline Gatorade, we lined up for the second-half kick-off. The ball popped off the tee and all 10 of us tore off down the field. Twenty yards into my straight-line sprint, a sniper somewhere in the cheap cheats popped one off and hit me square in the left groin, tearing the muscle off the bone with a yank that rattled the iron off of heaven's gate. THWAP!

The pop splayed my left leg off to the side. I reached for my groin and hopped on one foot. Total malfunction, but I was still on the field in the middle of the play. And I still had a job to do. The returner broke a tackle and ran through the wedge, coming right at me. I'd have to make this tackle regardless. There are things on the line, after all: pride, glory, other stuff. Hopping along like that on the 50-yard-line, some things get put in perspective. One, Scotty O. was right; I should have warmed back up. Two, I'm fucked. Three, somebody please tackle this man.

Just then a teammate tripped up the returner, and he came to rest five yards in front of me. I turned and limped to our sideline. As I reached the chalk, I got dizzy and almost fainted. My vision blurred, tunneled, then steadied again.

"What happened?" asked Greek.

"Something popped."

"Where?"

"Here." I pointed to my groin.

"OK, give it a minute and see how it feels."

"Alright." I turned my back to Greek and walked away gingerly. I knew I was done for.

I spent the rest of the game on the sideline with an ice bag stuck down my crotch. After the game I went home with instructions to return first thing in the morning to evaluate the injury. A pulled groin, they thought. No biggie. My sister Carol and brother-in-law Jeff were in town for the game. We went out to dinner, a Brazilian meat-on-a-stick restaurant downtown. I limped and hopped between the tables and chairs. People looked at me strangely. I was also meat on a stick.

The next morning I limped and hopped into the facility. My upper-inner thigh and pubic region had swelled up. I was walking timidly, slowly, straight-leggedly. Week 5 and I was crippled.

Injury treatment in the NFL, and in all levels of football, follows a certain protocol. Page one of the trainer's manual is ice and electrical stimulation, or "stim." Ice and stim; ice and stim; ice and stim. The stim uses electrical charges that pulse through two positive and two negative wire lines, like jumper cables, and are fixed to conductive pads and stuck on the skin, forming a picture frame around the injured area. The machine is turned on and electricity surges diagonally through the meat, stimulating the healing process. The muscle jumps as the electricity flows.

On top of the electrical pads, a bag of ice is fixed—form fitting and expertly tied. But it ain't just a bag of ice. There is an art to tying a bag of ice. All of the air must be sucked out of the bag before it can be twisted and tied: air tight. And it can't be ice cubes. They don't conform to the contours of the skin. It needs to be ice pebbles, ice chips, ice dust, stuff that will wrap around the injured area and freeze the muscle into a submissive post-injury state. That stops the swelling by slowing the blood flow, thus—stay with me here—speeding up the healing process.

The combination of an electric surge pulsing through the body, intended to stimulate blood flow, and an all-encompassing ice bag, intended to slow down the blood flow, might seem contradictory to someone in a position to consider it. But I was not in a position to consider it.

What's that, Nate? You want to rest it? Wait until it feels better before you start working it? No thingamajigs? Ha! You don't know anything about the human body, do you? We have to speed up the healing process! Your body's natural reaction to the injury is incorrect. We can't trust it, Nate. We need to manipulate the body's natural healing process, send shocks to it, changes of temperature, strain it to the point of exhaustion, stretch it to the point of snapping, blast it with powerful anti-inflammatories and painkillers, then shock/temperature change again, strain/stretch again, pills again, and repeat. That's how you heal the human body, Nate. Make sense?

Ice and stim, an MRI, back to the facility for more ice and stim. The training room has a sterilized smell to it: salves and creams and freshly laundered towels and cleaning supplies. I hated it, if only because I knew what the smell meant: I was injured again.

I lay on the table in the back corner sulking with an ice pack wedged in my taint, electrodes pumping diagonally through my testicles, an electric chair for my spermatazoa. I was waiting for our team doctor to arrive and assess the situation. Once the MRI results are received, the doctor meets with the athletic trainer. They discuss the findings, come up with a course of treatment, and then they brief the head coach. Once everyone is on the same page, the player is notified. Make sense?

Dr. Schlegel, one of our two team doctors, walked out of Greek's office and came to my table with an excellent poker face. "What's the word, Doc?"