-probably heard about this story already but he was on the Rich Eisen Show the other day. what a badass. this guy was in and out of firefights during his offseasons at Texas after getting on the team at age 29. oh and he's currently finishing his master's degree. someone make this guy a pro.

http://www.expressnews.com/sports/c...ht-not-be-done-with-6156523.php#photo-3436694

UT’s Green Beret might not be done with football yet

By Mike Finger

March 24, 2015 Updated: March 25, 2015 11:42am

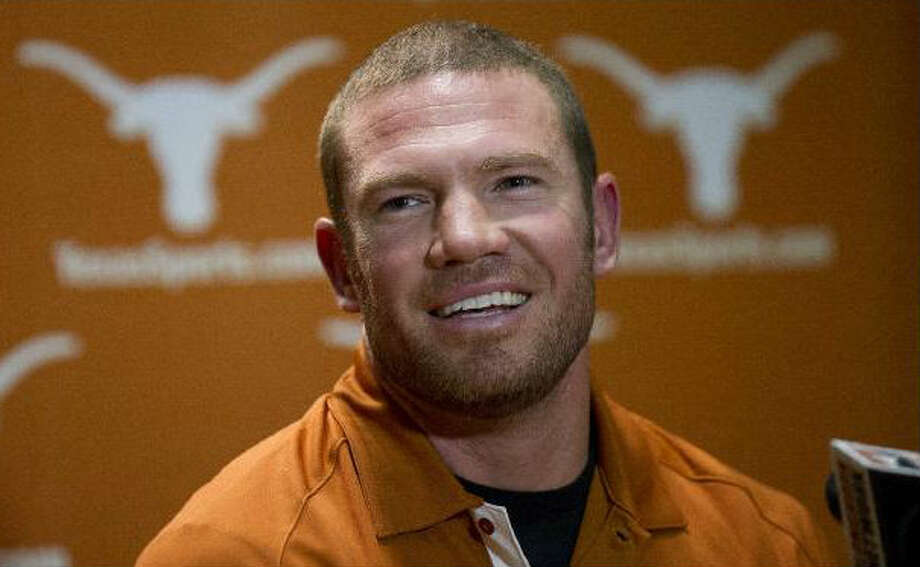

AUSTIN — An NFL scout told Nate Boyer he looked out of place Tuesday. He should have seen him last summer.

Sure, a 34-year-old man running through drills with a bunch of college seniors at Texas’ pro day might be a bit of a curiosity. Now picture that same guy in the middle of an Afghan desert, hunched over a dusty, scuffed American football, then firing it backwards between his legs, over and over again, until he attracted a crowd of confounded villagers.

“They’d come out and watch,” Boyer, a former Green Beret, said of his down time during one of several deployments with the U.S. Army Special Forces. “Just part of my trip.”

Boyer has a way of shrugging his shoulders and making everything he describes sound normal, even though almost none of it is. A decade ago, he decided to join the military not out of patriotism, but because he wanted to do more after serving as a relief worker in the Sudan.

After five years in the Middle East with the Special Forces, he enrolled in college at UT with the intent of playing football — even though he hadn’t even been on his high-school team. Eventually, he figured out his best chance to play was learning how to be a deep-snapper, so he did it.

Boyer wound up starting 38 consecutive games on the Longhorns’ special teams, even though he left the program every summer to fulfill his National Guard service and join a task force in Afghanistan. Last month, he received his honorable discharge.

Tuesday on the Longhorns’ practice fields, he was snapping footballs for NFL talent evaluators, in hopes that one might think enough of his ability to give him a shot.

“I’m not expecting anything,” Boyer said. “I’d be grateful for an opportunity. I’m not entitled. Nobody owes me anything.”

To prepare himself for pro day, Boyer said, he forced himself to gain more than 20 pounds in two months. Spending every college offseason in the desert meant that he never had the chance to build his muscular frame much bigger than 190 pounds. Tuesday, he weighed in at 216.

He also boasted a larger entourage, with a film crew following his every move for a documentary about his pro day experience. Having graduated with a master’s degree in advertising, Boyer has been spending time in Los Angeles, where he’s met other filmmakers in hopes of raising awareness about alarming suicide rates among veterans, and about what his fellow military members are doing in the Middle East.

“I’ve never been a political person,” Boyer said. “Most of the guys over there fighting aren’t, either. … They’re trying to help people in a place that doesn’t have what we have. It’s a good thing they’re doing. Don’t forget about the guys that are still there.”

Boyer said he’d like to address some of those issues in a film of his own someday, and he’s already found work as a military consultant on another movie. So he has options beyond football.

But even if he admitted Tuesday might have been his “last hurrah” on the gridiron, he thought he might have made enough of an impression to get an invitation to an NFL training camp.

“They always talk about intangibles,” Boyer said. “I think I’ve got a few.”

http://www.expressnews.com/sports/c...ht-not-be-done-with-6156523.php#photo-3436694

UT’s Green Beret might not be done with football yet

By Mike Finger

March 24, 2015 Updated: March 25, 2015 11:42am

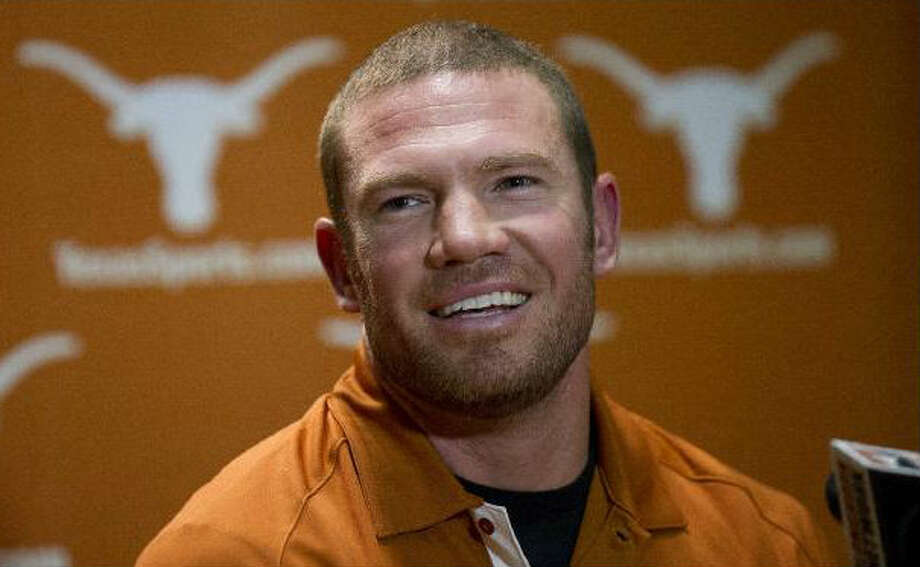

AUSTIN — An NFL scout told Nate Boyer he looked out of place Tuesday. He should have seen him last summer.

Sure, a 34-year-old man running through drills with a bunch of college seniors at Texas’ pro day might be a bit of a curiosity. Now picture that same guy in the middle of an Afghan desert, hunched over a dusty, scuffed American football, then firing it backwards between his legs, over and over again, until he attracted a crowd of confounded villagers.

“They’d come out and watch,” Boyer, a former Green Beret, said of his down time during one of several deployments with the U.S. Army Special Forces. “Just part of my trip.”

Boyer has a way of shrugging his shoulders and making everything he describes sound normal, even though almost none of it is. A decade ago, he decided to join the military not out of patriotism, but because he wanted to do more after serving as a relief worker in the Sudan.

After five years in the Middle East with the Special Forces, he enrolled in college at UT with the intent of playing football — even though he hadn’t even been on his high-school team. Eventually, he figured out his best chance to play was learning how to be a deep-snapper, so he did it.

Boyer wound up starting 38 consecutive games on the Longhorns’ special teams, even though he left the program every summer to fulfill his National Guard service and join a task force in Afghanistan. Last month, he received his honorable discharge.

Tuesday on the Longhorns’ practice fields, he was snapping footballs for NFL talent evaluators, in hopes that one might think enough of his ability to give him a shot.

“I’m not expecting anything,” Boyer said. “I’d be grateful for an opportunity. I’m not entitled. Nobody owes me anything.”

To prepare himself for pro day, Boyer said, he forced himself to gain more than 20 pounds in two months. Spending every college offseason in the desert meant that he never had the chance to build his muscular frame much bigger than 190 pounds. Tuesday, he weighed in at 216.

He also boasted a larger entourage, with a film crew following his every move for a documentary about his pro day experience. Having graduated with a master’s degree in advertising, Boyer has been spending time in Los Angeles, where he’s met other filmmakers in hopes of raising awareness about alarming suicide rates among veterans, and about what his fellow military members are doing in the Middle East.

“I’ve never been a political person,” Boyer said. “Most of the guys over there fighting aren’t, either. … They’re trying to help people in a place that doesn’t have what we have. It’s a good thing they’re doing. Don’t forget about the guys that are still there.”

Boyer said he’d like to address some of those issues in a film of his own someday, and he’s already found work as a military consultant on another movie. So he has options beyond football.

But even if he admitted Tuesday might have been his “last hurrah” on the gridiron, he thought he might have made enough of an impression to get an invitation to an NFL training camp.

“They always talk about intangibles,” Boyer said. “I think I’ve got a few.”