- Joined

- Feb 9, 2014

- Messages

- 20,922

- Name

- Peter

http://deadspin.com/brett-favres-vikings-had-a-bounty-program-too-1788188711

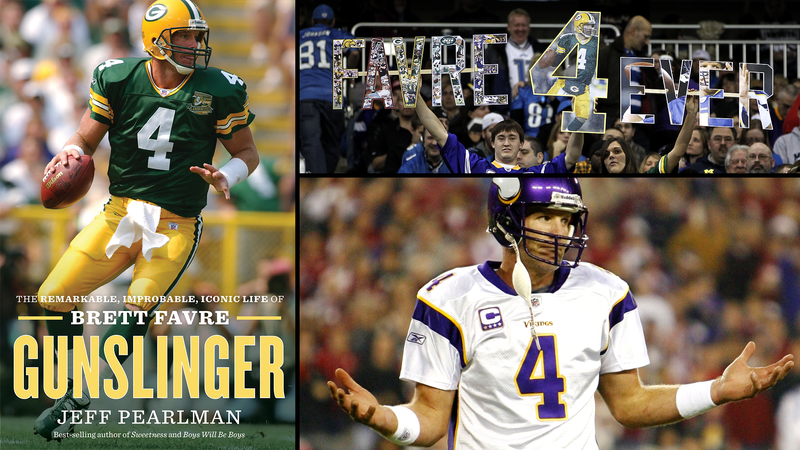

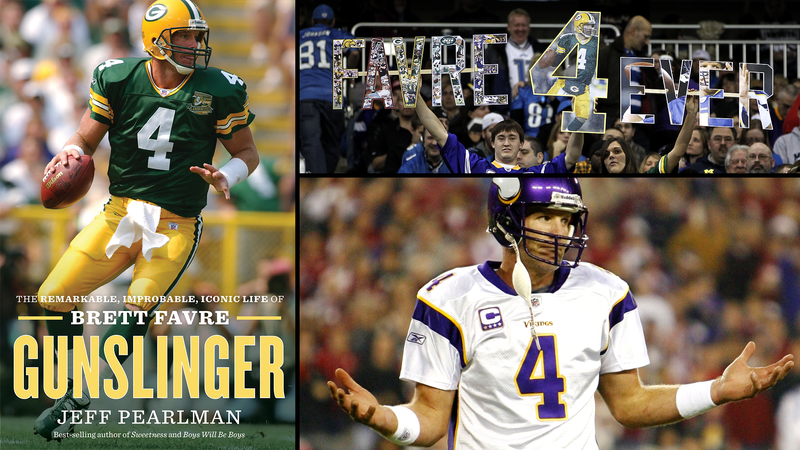

This excerpt from Gunslinger: The Remarkable, Improbable, Iconic Life of Brett Favre by Jeff Pearlman is reprinted with the permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Buy it here.

Brett Favre's Vikings Had A "Bounty" Program Too

Jeff Pearlman

On September 8, 2008, a year before Brett Favre would join the organization, the Minnesota Vikings traveled to Lambeau Field to face the Green Bay Packers. Aside from being Aaron Rodgers’s debut as a starter, the game was noteworthy for its physicality and aggressiveness. In the first half alone, the teams combined for 12 penalties for 86 yards.

It was a sloppy, messy, nasty affair, and in the days and weeks following the Packers’ 24–19 win, Minnesota’s coaches stewed. After watching the tape, they were convinced that Nick Barnett, Green Bay’s outstanding linebacker, had gone out of his way to injure Adrian Peterson, the Vikings halfback.

The rival franchises played again nine weeks later, and three days before kickoff a Minnesota coach stood up in a team meeting, mentioned Barnett by name, and said, “I will give $500 to anyone who takes this m**********r out of the game.”

This was hardly a shocking move in the Vikings’ locker room, where piles of money were regularly collected—then distributed as rewards—for injuring opposing stars. “It was part of the culture,” said Artis Hicks, a Minnesota offensive lineman.

“I had coaches start a pot and all the veterans put in an extra $100, $200, and if you hurt someone special, you get the money. There was a bottom line, and I think we all bought in: you’re there to win, and if taking out the other team’s best player helps you win, hey, it’s nothing personal. Just business.”

Although the Barnett affair occurred in 2008, Hicks insists the Vikings were no different a year later, when Brett Favre was quarterback. He recalled no one on the team complaining, nobody arguing with the approach. “This isn’t a game or culture for the fainthearted,” Hicks said. “You bleed, you suffer, you sacrifice, and if need be, you try and knock people out. It’s the NFL.”

Following the win over Dallas, the Vikings weren’t thinking about injuring opposing players, or taking someone out. That type of talk was often reserved for meetings with the league’s more aggressive teams; black-and-blue franchises like Green Bay, Chicago, and Pittsburgh.

Not the New Orleans Saints.

Morry Gash/AP Images

The NFC Championship game would be held on January 24, 2010, in the Crescent City, and while the Vikings certainly preferred a home contest, this was the next-best scenario. Minnesota’s coaches and players watched film of the Saints and came away both confident and surprisingly unimpressed.

In compiling a 13-3 record, New Orleans relied on a high-flying offense that, behind quarterback Drew Brees and a gaggle of dangerous wide receivers, led the NFL in total yards and touchdowns. One week earlier they advanced to the title game by whooping the Arizona Cardinals, 45–14.

It was the 10th time in 17 contests that New Orleans put up at least 30 points. “They scored and they scored quickly,” said Leslie Frazier, the Minnesota defensive coordinator. “You had to be ready.”

It was on the other side of the ball, though, where the Saints struggled. Gregg Williams, New Orleans’s defensive coordinator, was known as one of the sport’s great masterminds, and his ability to mix and disguise blitz packages became something of a calling card. Yet in 2009 the Saints ranked 20th in total defense, and their 35 sacks were just the 15th most in the league.

Not one player accumulated 90 tackles, and only one (defensive end Will Smith) eclipsed 10 sacks. Darren Sharper, the 34-year-old free safety, led the Saints with nine interceptions, but Favre’s former Green Bay teammate was a risk taker who—on tape—missed nearly as many tackles as he made.

A couple of days before the game Favre was asked about Williams’s group, and while he made certain to sound impressed, he wasn’t particularly concerned. The Cowboys had a defense. Look how that turned out.

There were lots of marvelous narratives for the press to spend a week lapping up. Favre was the 40-year-old man returning to the region where he was raised watching Archie Manning and the Saints. New Orleans, as a city, was still recovering from Hurricane Katrina, and a Super Bowl trip would do wonders for the region. Could the Vikings handle the noise inside the Louisiana Superdome? Could the Saints stop Peterson, the game’s best running back?

One thing that went undiscussed: Williams’s plan to handle Favre. In a way, it’s sort of surprising. For all the talk of the quarterback’s experience, no one asked Williams or his defensive players what—in hindsight—seems to be a perfectly sensible inquiry: At his advanced age, will you try and be more physically dominant than usual?

New Orleans knew the Vikings were dangerous. They also knew it would be a lot easier stopping Favre than Peterson. So the goal was, simply, to beat the snot out of the quarterback. To hit him and hit him and hit him some more. To wear him down and wipe him out. To cause him to limp and cause him to bleed.

“Make him pick his old ass up—that was our plan,” said Anthony Hargrove, a Saints defensive lineman. “Make Brett keep getting off the ground, and hope at some point he just said, ‘This is too much. I’m not getting up this time. I quit.’”

Favre was as likely to quit as the French Quarter was to go dry. But Williams’s men would try. Much like the Vikings, Saints players operated a reward system for hurting and incapacitating opposing stars. “It wasn’t a bounty, where you name one guy and offer money for him,” said Hargrove. “It was incentives for good plays, hard hits, changing the game. We all put in, and maybe you could get $100, $200, $500. That’s what it was.”

Would taking out Brett Favre be lucrative?

“There’s a brotherhood in football,” said Hargrove. “You never want to end anyone’s career. But at the same time, we have incentives...”

Of the 39 NFC Championship games played before 2010, few could match this one for excitement, energy, intrigue. The Vikings scored first on a 19-yard Peterson run, and the Saints fired back with a 38-yard pass from Brees to Pierre Thomas. The Vikings made it 14–7 on Favre’s 5-yard pass to Rice, the Saints tied the score at 14 on a 9-yarder from Brees to Devery Henderson. For fans in the stands, or fans viewing at home, it was everything you could hope for from a football game.

For Favre’s family members and friends, it was unwatchable. Jeff Favre, his younger brother, and Brandi Favre, his sister, were sitting in the Superdome, observing the beating, hands covering eyes, when they rose and left. They had attended plenty of games where Favre was the enemy. That was fine. But here, inside the Superdome, it felt more like a bullfight than a football game.

The matadors were the Saints, the weakened bull was Favre. The fans wanted blood. “Jeff and I got a cab and watched the rest from the hotel on TV,” Brandi said. “They were out to kill him. I knew they were trying to kill him. I’ve seen a lot of football, and that wasn’t normal. It was disgusting.”

“They were destroying him,” said Scott Favre. “The Saints—they still rub me the wrong way from that game.” “It was inexcusable,” said David Peterson, Favre’s cousin. “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.”

By one count, Favre was unnecessarily/gratuitously hit 13 times. Many were awful. Some were horrible. Two, in particular, were borderline criminal. In the quarter, Favre handed off to Percy Harvin on a jet sweep. The ball was out of his hands, and Harvin had taken five full steps in the opposite direction when—Pop!—defensive end Bobby McCray (all six feet six, 260 pounds of him) pulverized an unsuspecting Favre into the turf.

Later in the game, Favre dropped back to pass when McCray swarmed from the right and linebacker Remi Ayodele from straight ahead. Almost simultaneously, McCray dove into Favre’s knees while Ayodele bent him backward like a soggy slice of bread, then rolled atop his listless corpse and popped up. Favre hobbled to the sideline, favoring his left ankle. Hargrove later said that after running off the field, Ayodele yelled, “Gimme my money!”

In some ways, it was Favre’s lowest moment as a professional football player. In many ways, it was his greatest. The hits kept coming, and Favre kept standing up, brushing himself off, returning. The Saints pass rushers were bigger than the quarterback, stronger than the quarterback, younger than the quarterback. But they weren’t tougher than the quarterback. “He took every shot they had,” said Pat Morris, the Vikings’ offensive line coach. “And he didn’t flinch once.”

The Vikings were right—they were the better team. Faster, stronger, significantly more athletic. The Vikings won the possession and yardage battles—Peterson rushed for 122 yards and Minnesota gained 475 overall. But they also made lots of mistakes.

Favre threw two interceptions (he was 28 of 46 for the game, with 310 yards and a touchdown); there were six total fumbles. It was ugly execution. “The football turned seemingly slick,” wrote Jim Souhan of the Star Tribune, “as Andouille sausage plucked from a bowl of gumbo.”

Morry Gash/AP Images

And yet, after driving the Vikings to a 28–28 tie with 4:58 remaining, Favre had a chance for the win. Minnesota’s defense held the Saints’ offense to plays, and with 2:37 left in the fourth the Vikings started at their own 21. They had three time-outs. Two Peterson runs gained little, but on third and 8 Favre found Bernard Berrian for 10. The Vikings used their first time-out, and Favre returned to the field and hit Rice with a 20-yard bullet. The New Orleans defense looked winded.

On first and 10 from the Saints 47, Chester Taylor took a handoff and rumbled 14 yards to the Saints 33. New Orleans called its final time-out, and along the sideline Ryan Longwell, one of the league’s best kickers, was preparing to hit the field goal that would take the Vikings to their first Super Bowl since 1977.

There was now 1:06 left, and two runs—one by Taylor, one by Peterson—gained nothing. Minnesota called its second time-out with 19 seconds left, and it was third and 10 from the Saints 33. Longwell peeked at the field between kicks into a net. From here, the field goal would be 50 yards—not out of question, but a bit long for his range.

Then, stupidity. On the sideline Eric Bieniemy, the running backs coach, could be seen wildly waving his arms, trying to get someone—anyone—off the field. Minnesota accidentally had 12 offensive players in the huddle, which resulted in a 5-yard penalty that pushed the team back to the 38. The Vikings’ two requirements were clear: move a bit closer to give Longwell his best possible shot, and don’t—under any circumstance—turn over the football.

The play call was unremarkable: A short throw to Berrian in the flat. Favre lined up behind center. Peterson stood 5 yards to his rear, Berrian jogged in motion, right to left, then back toward the right. Sidney Rice was lined up in the right slot, tight end Visanthe Shiancoe in the left slot. It was a collection of Minnesota’s best weapons on the field for the season’s most important play. The stadium noise was deafening. Seats vibrated from the decibels.

Favre dropped back and rolled to the right. Berrian was never alone, but Shiancoe immediately turned around at the 35, where he was wide open. Favre either didn’t see him or didn’t feel comfortable with the throw. He did, however, spot Rice crisscrossing the middle of the field near the New Orleans 23. With his body moving hard to the right, Favre reared back and fired to Rice, who was running leftward.

The first person to see the pass was Tracy Porter, the speedy Saints cornerback. As the ball came closer and closer, Porter stepped in front of a lunging Rice, caught the football, and returned it to the Saints 47. “I did happen to read his eyes,” Porter said. “He was looking at Rice the whole time.” Favre dropped his head in disgust. There were seven seconds remaining.

Paul Allen, the Vikings’ radio voice, was incredulous—and screaming like a madman. “Why do you even ponder passing? You can take a knee and try a 56-yard field goal! This is not Detroit, man! This is the Super Bowl!”

New Orleans won 31–28 on a 40-yard Garrett Hartley field goal in overtime, and as the city celebrated its first conference title, Favre’s pain was as deep physically as it was emotionally. He could barely walk. His legs and torso were covered with black-and-blue craters. “Favre was pounded like a gavel, twisted like an Auntie Anne’s pretzel,” wrote Gene Wojciechowski of ESPN.com.

“You should have seen him sitting in front of that locker immediately after the loss. Red welts on his left arm. Blood on his upper right shoulder. A puffy left wrist. A raw gash on the same wrist. A swollen left ankle. A tender right thigh and lower back ... He was 40 at kickoff. He was 60 at the final whistle.”

“He looked like Joe Frazier after having gone 15 rounds with Muhammad Ali,” said Peter King. “There were three or four roughing-the-passer penalties that were never called, and he paid a big price in pain.”

Favre admitted, in hindsight, that he should have run the ball (there was room), though his scrambling days were the stuff of yesteryear and his ankle the size of a baby panda.

One by one, teammates stopped by to pay their respects. Rice hugged him for a solid 30 seconds. Peterson whispered something into his ear. “I appreciate you,” Favre replied softly. Harvin approached, wrapped his arms around the old quarterback. The eyes of both men were red and watery.

In the months that followed, much was written about what would become known as Bountygate—Williams’s alleged system of paying his players to hurt opponents. Asshole Face, the New Orleans head coach, was suspended for an entire season, and the team’s general manager, as well as Williams and assistant coach Joe Vitt, also faced temporary bans. The organization was fined $500,000 and forced two forfeit draft selections, and four players were suspended for their involvement. It was one of the biggest scandals in the 92-year history of the NFL.

For the league’s 1,600 or so players, however, it was much ado about nothing. Yes, a curtain had been pulled back on life in professional football. But the majority of veterans greeted the news with a shrug. Thomas Jones, Favre’s halfback with the Jets, found himself laughing at the uninformed ramblings from people making outside assessments. “What would make you think someone who is not in that environment would even have the slight idea of what we’re feeling, what we’re thinking?”

he said. “It’s like the military. Those people who come back from Iraq—they look the same. But they’re not the same. In football, if I knock the shit out of somebody and he wasn’t looking, that means I’m a nasty guy. I’m gonna get a positive grade for being nasty. You’re not in your right state of mind. All you’re thinking is, ‘If I don’t knock the shit out of him, he’s gonna knock the shit out of me.’

If a dude pushes me in the back and I’m not looking, I’m f***ing pissed. Pissed. So the next time I get a chance to f****ing do something, I’m doing it. You’ve seen Braveheart? Braveheart is exactly what football is. The scene where the Irish and the English are all running toward each other, and they clash, and it’s all individual little f***ing battles.

“If you’re in a playoff game you know what the stakes are ... what you’ve put into getting here, and you’re not like, ‘I’m not gonna knock this guy out because I care about him.’ No, you want to intimidate the f*** out of him. Because I want him to be scared, so I have a better chance to win so I can win the Super Bowl and get my $50,000 bonus.’ You’re not thinking about someone’s well-being. You’re doing whatever it takes.”

Favre initially avoided talking about the scandal. He finally sat down for an interview with the NFL Network, and said he was neither upset nor haunted. Football, Favre said, is a rough and ugly game, played by rough and ugly people. “My feeling, and I mean this wholeheartedly, is I don’t care,” he said. “What bothers me is we didn’t win the game. They didn’t take me out of the game. They came close ... [but] I’m not gonna sit the last three minutes. I’m gonna go out there with bones sticking out of my skin and finish it.”

This excerpt from Gunslinger: The Remarkable, Improbable, Iconic Life of Brett Favre by Jeff Pearlman is reprinted with the permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Buy it here.

Brett Favre's Vikings Had A "Bounty" Program Too

Jeff Pearlman

On September 8, 2008, a year before Brett Favre would join the organization, the Minnesota Vikings traveled to Lambeau Field to face the Green Bay Packers. Aside from being Aaron Rodgers’s debut as a starter, the game was noteworthy for its physicality and aggressiveness. In the first half alone, the teams combined for 12 penalties for 86 yards.

It was a sloppy, messy, nasty affair, and in the days and weeks following the Packers’ 24–19 win, Minnesota’s coaches stewed. After watching the tape, they were convinced that Nick Barnett, Green Bay’s outstanding linebacker, had gone out of his way to injure Adrian Peterson, the Vikings halfback.

The rival franchises played again nine weeks later, and three days before kickoff a Minnesota coach stood up in a team meeting, mentioned Barnett by name, and said, “I will give $500 to anyone who takes this m**********r out of the game.”

This was hardly a shocking move in the Vikings’ locker room, where piles of money were regularly collected—then distributed as rewards—for injuring opposing stars. “It was part of the culture,” said Artis Hicks, a Minnesota offensive lineman.

“I had coaches start a pot and all the veterans put in an extra $100, $200, and if you hurt someone special, you get the money. There was a bottom line, and I think we all bought in: you’re there to win, and if taking out the other team’s best player helps you win, hey, it’s nothing personal. Just business.”

Although the Barnett affair occurred in 2008, Hicks insists the Vikings were no different a year later, when Brett Favre was quarterback. He recalled no one on the team complaining, nobody arguing with the approach. “This isn’t a game or culture for the fainthearted,” Hicks said. “You bleed, you suffer, you sacrifice, and if need be, you try and knock people out. It’s the NFL.”

Following the win over Dallas, the Vikings weren’t thinking about injuring opposing players, or taking someone out. That type of talk was often reserved for meetings with the league’s more aggressive teams; black-and-blue franchises like Green Bay, Chicago, and Pittsburgh.

Not the New Orleans Saints.

Morry Gash/AP Images

The NFC Championship game would be held on January 24, 2010, in the Crescent City, and while the Vikings certainly preferred a home contest, this was the next-best scenario. Minnesota’s coaches and players watched film of the Saints and came away both confident and surprisingly unimpressed.

In compiling a 13-3 record, New Orleans relied on a high-flying offense that, behind quarterback Drew Brees and a gaggle of dangerous wide receivers, led the NFL in total yards and touchdowns. One week earlier they advanced to the title game by whooping the Arizona Cardinals, 45–14.

It was the 10th time in 17 contests that New Orleans put up at least 30 points. “They scored and they scored quickly,” said Leslie Frazier, the Minnesota defensive coordinator. “You had to be ready.”

It was on the other side of the ball, though, where the Saints struggled. Gregg Williams, New Orleans’s defensive coordinator, was known as one of the sport’s great masterminds, and his ability to mix and disguise blitz packages became something of a calling card. Yet in 2009 the Saints ranked 20th in total defense, and their 35 sacks were just the 15th most in the league.

Not one player accumulated 90 tackles, and only one (defensive end Will Smith) eclipsed 10 sacks. Darren Sharper, the 34-year-old free safety, led the Saints with nine interceptions, but Favre’s former Green Bay teammate was a risk taker who—on tape—missed nearly as many tackles as he made.

A couple of days before the game Favre was asked about Williams’s group, and while he made certain to sound impressed, he wasn’t particularly concerned. The Cowboys had a defense. Look how that turned out.

There were lots of marvelous narratives for the press to spend a week lapping up. Favre was the 40-year-old man returning to the region where he was raised watching Archie Manning and the Saints. New Orleans, as a city, was still recovering from Hurricane Katrina, and a Super Bowl trip would do wonders for the region. Could the Vikings handle the noise inside the Louisiana Superdome? Could the Saints stop Peterson, the game’s best running back?

One thing that went undiscussed: Williams’s plan to handle Favre. In a way, it’s sort of surprising. For all the talk of the quarterback’s experience, no one asked Williams or his defensive players what—in hindsight—seems to be a perfectly sensible inquiry: At his advanced age, will you try and be more physically dominant than usual?

New Orleans knew the Vikings were dangerous. They also knew it would be a lot easier stopping Favre than Peterson. So the goal was, simply, to beat the snot out of the quarterback. To hit him and hit him and hit him some more. To wear him down and wipe him out. To cause him to limp and cause him to bleed.

“Make him pick his old ass up—that was our plan,” said Anthony Hargrove, a Saints defensive lineman. “Make Brett keep getting off the ground, and hope at some point he just said, ‘This is too much. I’m not getting up this time. I quit.’”

Favre was as likely to quit as the French Quarter was to go dry. But Williams’s men would try. Much like the Vikings, Saints players operated a reward system for hurting and incapacitating opposing stars. “It wasn’t a bounty, where you name one guy and offer money for him,” said Hargrove. “It was incentives for good plays, hard hits, changing the game. We all put in, and maybe you could get $100, $200, $500. That’s what it was.”

Would taking out Brett Favre be lucrative?

“There’s a brotherhood in football,” said Hargrove. “You never want to end anyone’s career. But at the same time, we have incentives...”

Of the 39 NFC Championship games played before 2010, few could match this one for excitement, energy, intrigue. The Vikings scored first on a 19-yard Peterson run, and the Saints fired back with a 38-yard pass from Brees to Pierre Thomas. The Vikings made it 14–7 on Favre’s 5-yard pass to Rice, the Saints tied the score at 14 on a 9-yarder from Brees to Devery Henderson. For fans in the stands, or fans viewing at home, it was everything you could hope for from a football game.

For Favre’s family members and friends, it was unwatchable. Jeff Favre, his younger brother, and Brandi Favre, his sister, were sitting in the Superdome, observing the beating, hands covering eyes, when they rose and left. They had attended plenty of games where Favre was the enemy. That was fine. But here, inside the Superdome, it felt more like a bullfight than a football game.

The matadors were the Saints, the weakened bull was Favre. The fans wanted blood. “Jeff and I got a cab and watched the rest from the hotel on TV,” Brandi said. “They were out to kill him. I knew they were trying to kill him. I’ve seen a lot of football, and that wasn’t normal. It was disgusting.”

“They were destroying him,” said Scott Favre. “The Saints—they still rub me the wrong way from that game.” “It was inexcusable,” said David Peterson, Favre’s cousin. “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.”

By one count, Favre was unnecessarily/gratuitously hit 13 times. Many were awful. Some were horrible. Two, in particular, were borderline criminal. In the quarter, Favre handed off to Percy Harvin on a jet sweep. The ball was out of his hands, and Harvin had taken five full steps in the opposite direction when—Pop!—defensive end Bobby McCray (all six feet six, 260 pounds of him) pulverized an unsuspecting Favre into the turf.

Later in the game, Favre dropped back to pass when McCray swarmed from the right and linebacker Remi Ayodele from straight ahead. Almost simultaneously, McCray dove into Favre’s knees while Ayodele bent him backward like a soggy slice of bread, then rolled atop his listless corpse and popped up. Favre hobbled to the sideline, favoring his left ankle. Hargrove later said that after running off the field, Ayodele yelled, “Gimme my money!”

In some ways, it was Favre’s lowest moment as a professional football player. In many ways, it was his greatest. The hits kept coming, and Favre kept standing up, brushing himself off, returning. The Saints pass rushers were bigger than the quarterback, stronger than the quarterback, younger than the quarterback. But they weren’t tougher than the quarterback. “He took every shot they had,” said Pat Morris, the Vikings’ offensive line coach. “And he didn’t flinch once.”

The Vikings were right—they were the better team. Faster, stronger, significantly more athletic. The Vikings won the possession and yardage battles—Peterson rushed for 122 yards and Minnesota gained 475 overall. But they also made lots of mistakes.

Favre threw two interceptions (he was 28 of 46 for the game, with 310 yards and a touchdown); there were six total fumbles. It was ugly execution. “The football turned seemingly slick,” wrote Jim Souhan of the Star Tribune, “as Andouille sausage plucked from a bowl of gumbo.”

Morry Gash/AP Images

And yet, after driving the Vikings to a 28–28 tie with 4:58 remaining, Favre had a chance for the win. Minnesota’s defense held the Saints’ offense to plays, and with 2:37 left in the fourth the Vikings started at their own 21. They had three time-outs. Two Peterson runs gained little, but on third and 8 Favre found Bernard Berrian for 10. The Vikings used their first time-out, and Favre returned to the field and hit Rice with a 20-yard bullet. The New Orleans defense looked winded.

On first and 10 from the Saints 47, Chester Taylor took a handoff and rumbled 14 yards to the Saints 33. New Orleans called its final time-out, and along the sideline Ryan Longwell, one of the league’s best kickers, was preparing to hit the field goal that would take the Vikings to their first Super Bowl since 1977.

There was now 1:06 left, and two runs—one by Taylor, one by Peterson—gained nothing. Minnesota called its second time-out with 19 seconds left, and it was third and 10 from the Saints 33. Longwell peeked at the field between kicks into a net. From here, the field goal would be 50 yards—not out of question, but a bit long for his range.

Then, stupidity. On the sideline Eric Bieniemy, the running backs coach, could be seen wildly waving his arms, trying to get someone—anyone—off the field. Minnesota accidentally had 12 offensive players in the huddle, which resulted in a 5-yard penalty that pushed the team back to the 38. The Vikings’ two requirements were clear: move a bit closer to give Longwell his best possible shot, and don’t—under any circumstance—turn over the football.

The play call was unremarkable: A short throw to Berrian in the flat. Favre lined up behind center. Peterson stood 5 yards to his rear, Berrian jogged in motion, right to left, then back toward the right. Sidney Rice was lined up in the right slot, tight end Visanthe Shiancoe in the left slot. It was a collection of Minnesota’s best weapons on the field for the season’s most important play. The stadium noise was deafening. Seats vibrated from the decibels.

Favre dropped back and rolled to the right. Berrian was never alone, but Shiancoe immediately turned around at the 35, where he was wide open. Favre either didn’t see him or didn’t feel comfortable with the throw. He did, however, spot Rice crisscrossing the middle of the field near the New Orleans 23. With his body moving hard to the right, Favre reared back and fired to Rice, who was running leftward.

The first person to see the pass was Tracy Porter, the speedy Saints cornerback. As the ball came closer and closer, Porter stepped in front of a lunging Rice, caught the football, and returned it to the Saints 47. “I did happen to read his eyes,” Porter said. “He was looking at Rice the whole time.” Favre dropped his head in disgust. There were seven seconds remaining.

Paul Allen, the Vikings’ radio voice, was incredulous—and screaming like a madman. “Why do you even ponder passing? You can take a knee and try a 56-yard field goal! This is not Detroit, man! This is the Super Bowl!”

New Orleans won 31–28 on a 40-yard Garrett Hartley field goal in overtime, and as the city celebrated its first conference title, Favre’s pain was as deep physically as it was emotionally. He could barely walk. His legs and torso were covered with black-and-blue craters. “Favre was pounded like a gavel, twisted like an Auntie Anne’s pretzel,” wrote Gene Wojciechowski of ESPN.com.

“You should have seen him sitting in front of that locker immediately after the loss. Red welts on his left arm. Blood on his upper right shoulder. A puffy left wrist. A raw gash on the same wrist. A swollen left ankle. A tender right thigh and lower back ... He was 40 at kickoff. He was 60 at the final whistle.”

“He looked like Joe Frazier after having gone 15 rounds with Muhammad Ali,” said Peter King. “There were three or four roughing-the-passer penalties that were never called, and he paid a big price in pain.”

Favre admitted, in hindsight, that he should have run the ball (there was room), though his scrambling days were the stuff of yesteryear and his ankle the size of a baby panda.

One by one, teammates stopped by to pay their respects. Rice hugged him for a solid 30 seconds. Peterson whispered something into his ear. “I appreciate you,” Favre replied softly. Harvin approached, wrapped his arms around the old quarterback. The eyes of both men were red and watery.

In the months that followed, much was written about what would become known as Bountygate—Williams’s alleged system of paying his players to hurt opponents. Asshole Face, the New Orleans head coach, was suspended for an entire season, and the team’s general manager, as well as Williams and assistant coach Joe Vitt, also faced temporary bans. The organization was fined $500,000 and forced two forfeit draft selections, and four players were suspended for their involvement. It was one of the biggest scandals in the 92-year history of the NFL.

For the league’s 1,600 or so players, however, it was much ado about nothing. Yes, a curtain had been pulled back on life in professional football. But the majority of veterans greeted the news with a shrug. Thomas Jones, Favre’s halfback with the Jets, found himself laughing at the uninformed ramblings from people making outside assessments. “What would make you think someone who is not in that environment would even have the slight idea of what we’re feeling, what we’re thinking?”

he said. “It’s like the military. Those people who come back from Iraq—they look the same. But they’re not the same. In football, if I knock the shit out of somebody and he wasn’t looking, that means I’m a nasty guy. I’m gonna get a positive grade for being nasty. You’re not in your right state of mind. All you’re thinking is, ‘If I don’t knock the shit out of him, he’s gonna knock the shit out of me.’

If a dude pushes me in the back and I’m not looking, I’m f***ing pissed. Pissed. So the next time I get a chance to f****ing do something, I’m doing it. You’ve seen Braveheart? Braveheart is exactly what football is. The scene where the Irish and the English are all running toward each other, and they clash, and it’s all individual little f***ing battles.

“If you’re in a playoff game you know what the stakes are ... what you’ve put into getting here, and you’re not like, ‘I’m not gonna knock this guy out because I care about him.’ No, you want to intimidate the f*** out of him. Because I want him to be scared, so I have a better chance to win so I can win the Super Bowl and get my $50,000 bonus.’ You’re not thinking about someone’s well-being. You’re doing whatever it takes.”

Favre initially avoided talking about the scandal. He finally sat down for an interview with the NFL Network, and said he was neither upset nor haunted. Football, Favre said, is a rough and ugly game, played by rough and ugly people. “My feeling, and I mean this wholeheartedly, is I don’t care,” he said. “What bothers me is we didn’t win the game. They didn’t take me out of the game. They came close ... [but] I’m not gonna sit the last three minutes. I’m gonna go out there with bones sticking out of my skin and finish it.”