- Joined

- Feb 9, 2014

- Messages

- 20,922

- Name

- Peter

https://theringer.com/nfl-information-war-data-advanced-stats-73b6eee2d39f#.qwtgyoity

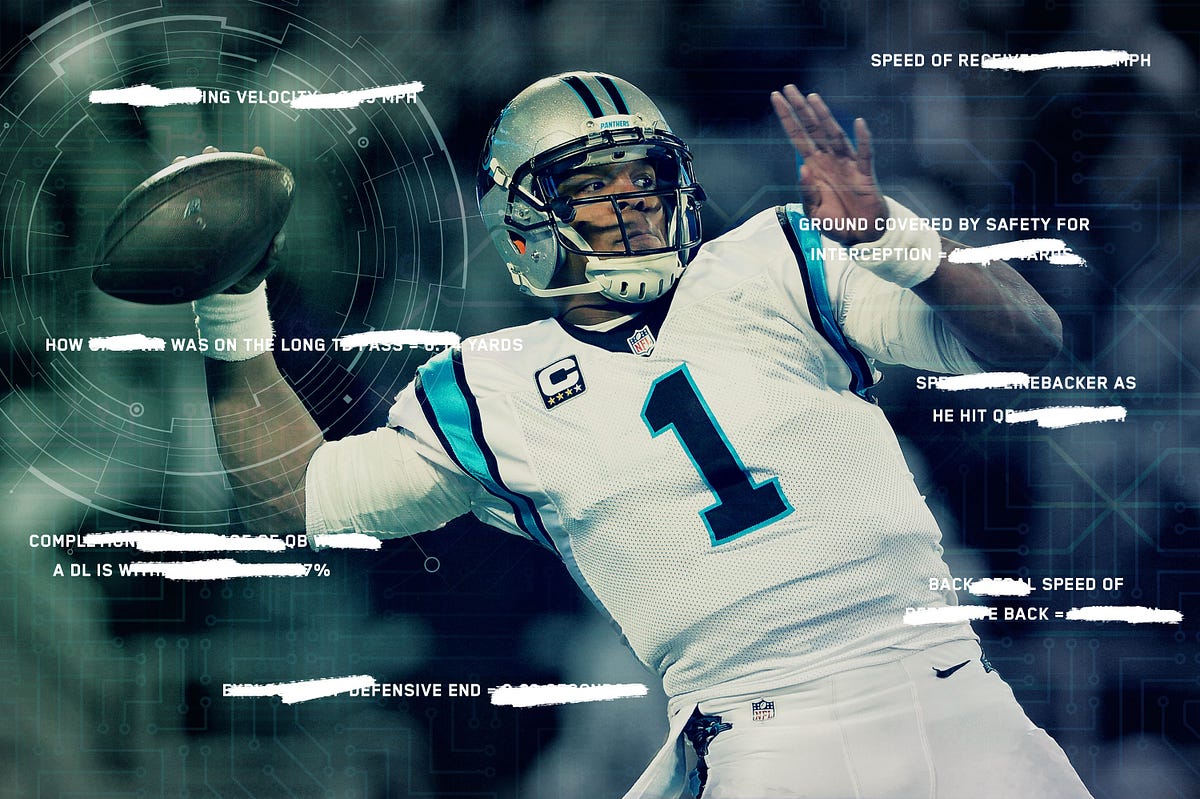

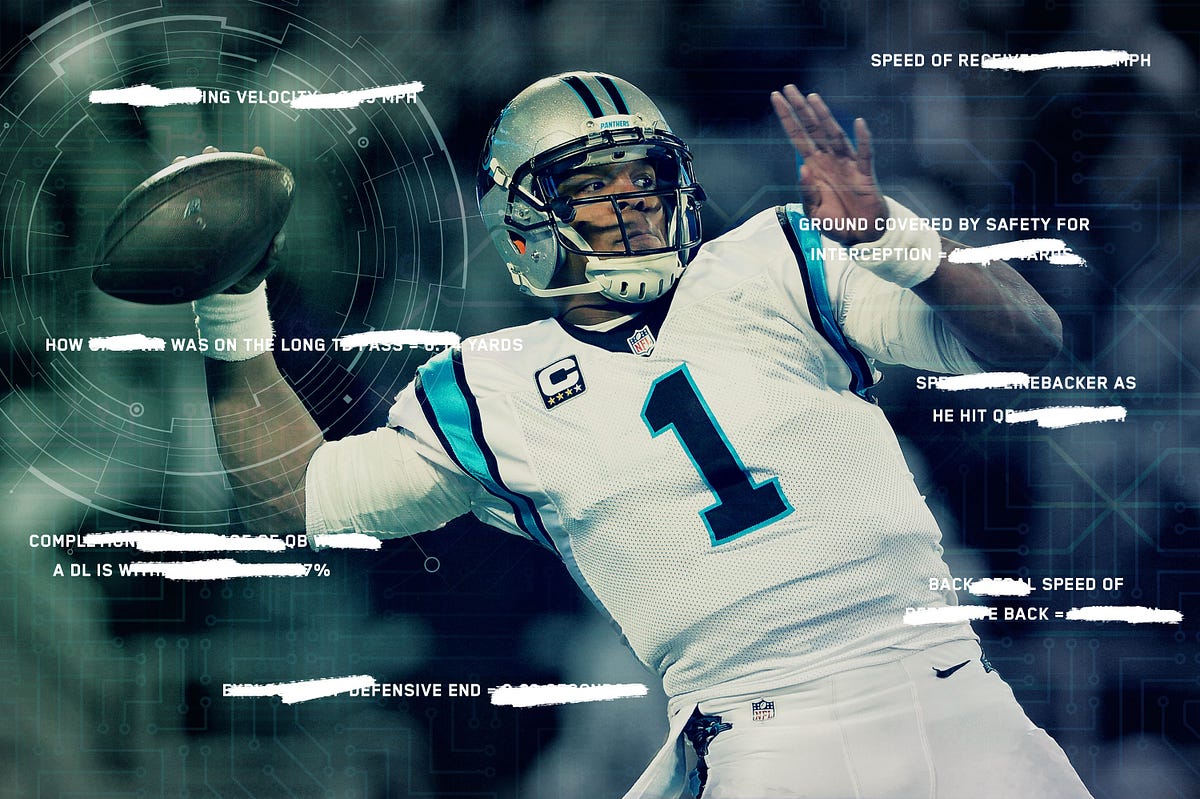

The NFL’s Brewing Information War

The fiercest matchup in football isn’t happening on the field — but it will determine the future of the game

By Kevin Clark

Staff Writer, The Ringer

Getty Images/Ringer illustration

When every important decision-maker in the NFL shuffled into a hotel conference room in Boca Raton, Florida, in March for the league’s annual meeting, the scene was initially predictable: Most of the head coaches wore golf shirts, and most everyone had found a way to make the meetings double as a family vacation. The atmosphere was festive, and the pools were full of league titans. It did not appear to be the setting for the opening salvo of a war over the future of the NFL, but that’s what it became.

The meeting shifted toward discussing whether coaches should be allowed to watch game film on the sidelines during contests, a practice never before allowed. According to multiple people who were in the room at the time, Ron Rivera, the head coach of the defending NFC champion Carolina Panthers, stood up and asked what the point of coaching was if, after preparing all week, video would be readily available on the sidelines anyway.

“Where does it end?” Rivera said this week in an interview with The Ringer. “Can you get text messages or go out there with an iPhone and figure out where to go? What are we creating? I know there are millennial players, but this is still a game created 100 years ago.”

Rivera’s stance was among the most notable scenes during a spring in which it became increasingly clear that technology’s role in football has created a divide. On one side, there are coaches who have an old-school view of the craft; on the other are the coaches, executives, and owners who anticipate the sport undergoing the same sort of data revolution that most industries experienced long ago.

The NFL could have the technological capabilities to make a sideline look like a Blade Runner reboot. But it already has a mountain of data — it’s just that the mountain is largely inaccessible. In an effort to facilitate progress, league officials in Boca Raton pitched the NFL’s latest data technology: a system that would allow franchises to view player-tracking data for all 32 teams.

If implemented, the technology would enable clubs to monitor every movement on the field for the first time, yielding raw data on player performance. For example: A team concerned about a slow cornerback could actually find out how much slower he is than Antonio Brown, who, according to data shared on a 2015 Thursday Night Football broadcast, posted a maximum speed of 21.8 mph during the season.

The proposal for teams to have access to all raw player-tracking data did not make it past the league’s Competition Committee, a group of team executives, owners, and coaches, according to an NFL official. Certain coaches griped about what might happen if other teams or the public had access to this data, and the committee told team representatives that it was too much, too soon, preventing the matter from reaching the teams for a vote at the March meeting.

“In other industries it is crazy to think you are going to limit innovation just to protect the people who aren’t ready,” said Brian Kopp, president of North America for Catapult Sports, which says it has deals with 19 NFL teams to provide practice data, but not game data. “Let’s make it all equally competitive, which is: You don’t figure it out, you start losing and you lose your job.”

Rivera, who’s coached the Panthers since 2011 and serves on a subcommittee of the NFL Competition Committee, said that introducing too much technology could “take the essence” out of the sport.

“I want to get beat on the field. I don’t want to get beat because someone used a tool or technology — that is not coaching at that point,” Rivera said. “I work all week, I’m preparing and kicking your ass. All of the sudden you see a piece of live video and you figure out, ‘Oh crap, that’s what he’s doing.’ And how fair is that?”

wo seasons ago, some NFL players began wearing two tiny chips in their shoulder pads during games. The program expanded to all players this past season, when Zebra Technologies, the company that produces the chips, also outfitted every stadium with receivers that decipher all movements on the field, measuring everything from player speed to how open a pass-catcher manages to get on a given play.

wo seasons ago, some NFL players began wearing two tiny chips in their shoulder pads during games. The program expanded to all players this past season, when Zebra Technologies, the company that produces the chips, also outfitted every stadium with receivers that decipher all movements on the field, measuring everything from player speed to how open a pass-catcher manages to get on a given play.

If you’re suddenly worried that you’re the only one missing out on crucial pieces of football analysis, rest assured, you’re not: Aside from a few nuggets sprinkled into television broadcasts, fans don’t have access to most league-wide data. More alarmingly, teams don’t have access to any league-wide data during the season, and, according to league officials, didn’t even get their own data from the 2015 season until three weeks ago.

Though football enthusiasts often praise the NFL for being forward-thinking, it has actually lagged behind other professional leagues amid an otherwise widespread analytics revolution, with a player-tracking section on NBA.com and MLB allowing the public to access its PITCHf/x data for research and modeling purposes.

While NFL teams have hired analysts for front-office roles and external parties have created websites aimed at tracking advanced statistics for fans and media, when league employees actually started to pitch head coaches on “Next Gen” statistics and technological advancements about four years ago, they were stunned at the reception.

One feature offered at the time was a small but potentially industry-changing tool. For decades, young assistant coaches had spent hours, often full nights, charting offensive plays, drawing what happened and what should have happened on a given play. The player-tracking tool could provide teams with precise maps of each player’s movement on a play, no pencils needed.

According to a senior NFL employee tasked with educating coaches about the latest tech, many bristled at the suggestion that manually charting plays wasn’t a worthwhile coaching endeavor. When the league countered that these advancements would free up assistants to do any number of other analytical tasks, coaches shrugged and moved on.

Those attempting to sway today’s coaches are dealing with more of the same: “What’s frustrating is that the opportunity is there, but as far as analysis, they are still stuck in the 1950s,” said Matt Richner, a football analytics expert who has consulted for NFL teams. “We should already know Cam Newton’s completion percentage when he’s within 2 yards of a defensive lineman. We should be able to easily measure his throwing windows. Instead, we get very basic data, like the Stone Age.”

other league in the world regulates game day actions as heavily as the NFL. Anything used on the field must pass through the Competition Committee, at a minimum. Any technology, no matter how basic, will not clear if it puts any party at a competitive disadvantage. This setup can slow progress, and it creates an incongruity that allows teams to digitally monitor players during the practice week in ways — checking heart rate, hydration — that they can’t during the second quarter of a game.

other league in the world regulates game day actions as heavily as the NFL. Anything used on the field must pass through the Competition Committee, at a minimum. Any technology, no matter how basic, will not clear if it puts any party at a competitive disadvantage. This setup can slow progress, and it creates an incongruity that allows teams to digitally monitor players during the practice week in ways — checking heart rate, hydration — that they can’t during the second quarter of a game.

But some information trickles out during game day: CBS has access to player-tracking data as part of its Thursday night package, enabling it to quickly reference the speed of Broncos wide receiver Emmanuel Sanders, for instance; NBC received the data in one Sunday Night Football game last year and will be able to use it in its upcoming Thursday night slate this season as well, said Hans Schroeder, the NFL’s senior vice president of media strategy, business development, and sales.

Xbox One has an app that can show basic player movement and speed. Because it is not a competitive issue, broadcasters don’t have to jump through hoops to see the statistics, as teams do. In fact, media entities with Next Gen stats agreements have more information in real time than teams.

“There are opportunities to monetize, and that’s important,” Schroeder said. “We are making a big investment in the rollout of [the shoulder pad chips], and it is responsible from a financial place to get some returns to offset that investment.”

Media executives at companies that broadcast NFL games, however, have said there’s been a lukewarm response to the offerings, with networks worrying that the information is not yet digestible enough for the casual football viewer. Though Schroeder eventually expects the statistics to become a bigger part of the broadcast, he doesn’t anticipate fans noticing a big difference in how the game is analyzed on television.

“We don’t want it to feel like a science contest,” he said. “To the person on the couch at home, we’re respectful. A lot of people grew up playing [and know the game]. What we are looking at are ways we can tell the story better.” When weighing in on the debate over how much technology should be in football, Schroeder said that in his experience, the Competition Committee has been helpful.

“Football operations, NFL executive vice president Troy Vincent, the Competition Committee — they are looking for an appropriate and responsible way to evolve,” he said. “Any time you have 32 different coaches, there will be differences in perspective.”

Those different perspectives surface nearly every time coaches get together. Most arguments against technology, according to people who have witnessed such conversations, have revolved around unintended consequences: Will they have to hire additional assistants to decipher the data and video? Will opponents be able to find a new edge?

Will implementing further technological developments delay the league’s ability to deal with more glaring issues — the catch rule and instant replay, for instance — that need fixing? The Competition Committee tabled the question of using Microsoft tablets to view game film on the sidelines in March and again in May, but they’ll revisit the matter after this season.

“I think the coaches, and I don’t blame them for it, I think they’ve put their hand up and said, ‘Hold it, not so fast, let us just kind of digest how this change is going to impact us,’” Falcons president and Competition Committee head Rich McKay told SiriusXM after May’s meeting.

August 2012, Manchester City, one of the biggest and richest soccer teams on the planet, did something that many of its peers would characterize as completely insane: It posted proprietary player data online, hoping to kickstart an analytics revolution. Even if it didn’t benefit Manchester City, the team’s analyst, Gavin Fleig,explained that he was hoping a famed sabermetrician like Bill James would emerge from the sport.

August 2012, Manchester City, one of the biggest and richest soccer teams on the planet, did something that many of its peers would characterize as completely insane: It posted proprietary player data online, hoping to kickstart an analytics revolution. Even if it didn’t benefit Manchester City, the team’s analyst, Gavin Fleig,explained that he was hoping a famed sabermetrician like Bill James would emerge from the sport.

Some NFL owners fantasize about an equivalent data dump in the NFL, but that prospect remains remote. The league will experiment further — for instance, footballs will have chips in them this preseason to measure their movement — but the ultimate application of all of the data is still a mystery.

“I don’t know that it’s ever going to be done in that same way [as other sports],” said Jill Stelfox, vice president and general manager of location solutions at Zebra Technologies. She said the company’s job is to collect the data, not apply it, so it does not have a strong feeling on where the data should go, but she anticipates that the NFL and the networks that broadcast games will find ways to make the information more digestible. “Do [fans] need every piece of X and Y to enjoy the data? I don’t think so,” she said.

In 2016, the NFL is not the only body grappling with how to implement technology, but it stands on the edge of a crucial and contentious debate about what to use and when. “Other owners and coaches are seeing each other in the hallways after these discussions,” one owner said. “And we can’t believe what people are saying.”

The NFL’s Brewing Information War

The fiercest matchup in football isn’t happening on the field — but it will determine the future of the game

By Kevin Clark

Staff Writer, The Ringer

Getty Images/Ringer illustration

When every important decision-maker in the NFL shuffled into a hotel conference room in Boca Raton, Florida, in March for the league’s annual meeting, the scene was initially predictable: Most of the head coaches wore golf shirts, and most everyone had found a way to make the meetings double as a family vacation. The atmosphere was festive, and the pools were full of league titans. It did not appear to be the setting for the opening salvo of a war over the future of the NFL, but that’s what it became.

The meeting shifted toward discussing whether coaches should be allowed to watch game film on the sidelines during contests, a practice never before allowed. According to multiple people who were in the room at the time, Ron Rivera, the head coach of the defending NFC champion Carolina Panthers, stood up and asked what the point of coaching was if, after preparing all week, video would be readily available on the sidelines anyway.

“Where does it end?” Rivera said this week in an interview with The Ringer. “Can you get text messages or go out there with an iPhone and figure out where to go? What are we creating? I know there are millennial players, but this is still a game created 100 years ago.”

Rivera’s stance was among the most notable scenes during a spring in which it became increasingly clear that technology’s role in football has created a divide. On one side, there are coaches who have an old-school view of the craft; on the other are the coaches, executives, and owners who anticipate the sport undergoing the same sort of data revolution that most industries experienced long ago.

The NFL could have the technological capabilities to make a sideline look like a Blade Runner reboot. But it already has a mountain of data — it’s just that the mountain is largely inaccessible. In an effort to facilitate progress, league officials in Boca Raton pitched the NFL’s latest data technology: a system that would allow franchises to view player-tracking data for all 32 teams.

If implemented, the technology would enable clubs to monitor every movement on the field for the first time, yielding raw data on player performance. For example: A team concerned about a slow cornerback could actually find out how much slower he is than Antonio Brown, who, according to data shared on a 2015 Thursday Night Football broadcast, posted a maximum speed of 21.8 mph during the season.

The proposal for teams to have access to all raw player-tracking data did not make it past the league’s Competition Committee, a group of team executives, owners, and coaches, according to an NFL official. Certain coaches griped about what might happen if other teams or the public had access to this data, and the committee told team representatives that it was too much, too soon, preventing the matter from reaching the teams for a vote at the March meeting.

“In other industries it is crazy to think you are going to limit innovation just to protect the people who aren’t ready,” said Brian Kopp, president of North America for Catapult Sports, which says it has deals with 19 NFL teams to provide practice data, but not game data. “Let’s make it all equally competitive, which is: You don’t figure it out, you start losing and you lose your job.”

Rivera, who’s coached the Panthers since 2011 and serves on a subcommittee of the NFL Competition Committee, said that introducing too much technology could “take the essence” out of the sport.

“I want to get beat on the field. I don’t want to get beat because someone used a tool or technology — that is not coaching at that point,” Rivera said. “I work all week, I’m preparing and kicking your ass. All of the sudden you see a piece of live video and you figure out, ‘Oh crap, that’s what he’s doing.’ And how fair is that?”

If you’re suddenly worried that you’re the only one missing out on crucial pieces of football analysis, rest assured, you’re not: Aside from a few nuggets sprinkled into television broadcasts, fans don’t have access to most league-wide data. More alarmingly, teams don’t have access to any league-wide data during the season, and, according to league officials, didn’t even get their own data from the 2015 season until three weeks ago.

Though football enthusiasts often praise the NFL for being forward-thinking, it has actually lagged behind other professional leagues amid an otherwise widespread analytics revolution, with a player-tracking section on NBA.com and MLB allowing the public to access its PITCHf/x data for research and modeling purposes.

While NFL teams have hired analysts for front-office roles and external parties have created websites aimed at tracking advanced statistics for fans and media, when league employees actually started to pitch head coaches on “Next Gen” statistics and technological advancements about four years ago, they were stunned at the reception.

One feature offered at the time was a small but potentially industry-changing tool. For decades, young assistant coaches had spent hours, often full nights, charting offensive plays, drawing what happened and what should have happened on a given play. The player-tracking tool could provide teams with precise maps of each player’s movement on a play, no pencils needed.

According to a senior NFL employee tasked with educating coaches about the latest tech, many bristled at the suggestion that manually charting plays wasn’t a worthwhile coaching endeavor. When the league countered that these advancements would free up assistants to do any number of other analytical tasks, coaches shrugged and moved on.

Those attempting to sway today’s coaches are dealing with more of the same: “What’s frustrating is that the opportunity is there, but as far as analysis, they are still stuck in the 1950s,” said Matt Richner, a football analytics expert who has consulted for NFL teams. “We should already know Cam Newton’s completion percentage when he’s within 2 yards of a defensive lineman. We should be able to easily measure his throwing windows. Instead, we get very basic data, like the Stone Age.”

But some information trickles out during game day: CBS has access to player-tracking data as part of its Thursday night package, enabling it to quickly reference the speed of Broncos wide receiver Emmanuel Sanders, for instance; NBC received the data in one Sunday Night Football game last year and will be able to use it in its upcoming Thursday night slate this season as well, said Hans Schroeder, the NFL’s senior vice president of media strategy, business development, and sales.

Xbox One has an app that can show basic player movement and speed. Because it is not a competitive issue, broadcasters don’t have to jump through hoops to see the statistics, as teams do. In fact, media entities with Next Gen stats agreements have more information in real time than teams.

“There are opportunities to monetize, and that’s important,” Schroeder said. “We are making a big investment in the rollout of [the shoulder pad chips], and it is responsible from a financial place to get some returns to offset that investment.”

Media executives at companies that broadcast NFL games, however, have said there’s been a lukewarm response to the offerings, with networks worrying that the information is not yet digestible enough for the casual football viewer. Though Schroeder eventually expects the statistics to become a bigger part of the broadcast, he doesn’t anticipate fans noticing a big difference in how the game is analyzed on television.

“We don’t want it to feel like a science contest,” he said. “To the person on the couch at home, we’re respectful. A lot of people grew up playing [and know the game]. What we are looking at are ways we can tell the story better.” When weighing in on the debate over how much technology should be in football, Schroeder said that in his experience, the Competition Committee has been helpful.

“Football operations, NFL executive vice president Troy Vincent, the Competition Committee — they are looking for an appropriate and responsible way to evolve,” he said. “Any time you have 32 different coaches, there will be differences in perspective.”

Those different perspectives surface nearly every time coaches get together. Most arguments against technology, according to people who have witnessed such conversations, have revolved around unintended consequences: Will they have to hire additional assistants to decipher the data and video? Will opponents be able to find a new edge?

Will implementing further technological developments delay the league’s ability to deal with more glaring issues — the catch rule and instant replay, for instance — that need fixing? The Competition Committee tabled the question of using Microsoft tablets to view game film on the sidelines in March and again in May, but they’ll revisit the matter after this season.

“I think the coaches, and I don’t blame them for it, I think they’ve put their hand up and said, ‘Hold it, not so fast, let us just kind of digest how this change is going to impact us,’” Falcons president and Competition Committee head Rich McKay told SiriusXM after May’s meeting.

Some NFL owners fantasize about an equivalent data dump in the NFL, but that prospect remains remote. The league will experiment further — for instance, footballs will have chips in them this preseason to measure their movement — but the ultimate application of all of the data is still a mystery.

“I don’t know that it’s ever going to be done in that same way [as other sports],” said Jill Stelfox, vice president and general manager of location solutions at Zebra Technologies. She said the company’s job is to collect the data, not apply it, so it does not have a strong feeling on where the data should go, but she anticipates that the NFL and the networks that broadcast games will find ways to make the information more digestible. “Do [fans] need every piece of X and Y to enjoy the data? I don’t think so,” she said.

In 2016, the NFL is not the only body grappling with how to implement technology, but it stands on the edge of a crucial and contentious debate about what to use and when. “Other owners and coaches are seeing each other in the hallways after these discussions,” one owner said. “And we can’t believe what people are saying.”