- Joined

- Feb 9, 2014

- Messages

- 20,922

- Name

- Peter

Harrington was drafted by the Lions as the third pick overall in the 2002 draft.

"Harrington's career in Detroit was largely unsuccessful. Front office mismanagement, woeful offensive line protection, lack of talent at other skill positions, and an erratic philosophical change in the team's identity to a conservative West Coast Offense (WCO) oriented attack under Head Coach Steve Mariucci may have played a factor in Harrington not realizing his potential professionally.

Despite his difficult times in Detroit, he remained unwaveringly optimistic and was thus dubbed "Joey Blue-Skies" and "Joey Sunshine" by sarcastic Lions' fans and beat writers who grew tired of his predictable post-game commentary as the losses continued to mount."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joey_Harrington

Sounds pretty close to the travails of Sam Bradford while with the Rams. Harrington then went on to play for the Dolphins, Falcons, and Saints. He talks about his career in the article below.

******************************************************************************

https://thecauldron.si.com/despite-...-career-was-a-success-179aeca1b1e7#.kmrkcy287

(AP)

Despite What You May Think, My NFL Career Was A Success

There were times — a good majority of my career — when I didn’t play well, but the ups and downs helped set me up in life.

By Joey Harrington

Seven seasons have come and gone since I retired from the NFL. I went out on my terms, when I was ready. I fulfilled all I set out to do.

At least at the pro level.

If you find that curious, I’m going to explain what happened at every step in my career, and why — regardless of outside perceptions — I think it was a rousing success, but first let me let you in on a little secret: My biggest football dream growing up was to play in the Rose Bowl, not in the NFL.

Sadly, it’s the one thing I was never able to make happen.

I was 11 years old when my dad first took me to Pasadena. It was Bo Schembechler’s last game — Michigan vs. USC — and we’d arrived hours before kickoff. We walked around and looked at all the plaques on the wall outside the Rose Bowl — the ones that list all the previous MVPs.

That’s when I did the math.

“Dad, that one’s going to be me,” I said, looking at the still-empty space for the year 2000. “Right there. That one.”

When that year finally came around, my junior year at Oregon, I reminded him again before the annual Civil War game against Oregon State. We were going to Pasadena, I told him. I wound up throwing five picks in a 23–13 loss. Our shot at the Rose Bowl was gone.

Making that game was always my biggest football ambition. Not to improve my draft stock, not to be a pro football Hall of Famer. Play college football, go to the Rose Bowl, set myself up for success and life, and have fun. That was it.

When I came back for my senior year, we had the best regular season (to that point) in Oregon history, but were left out of the BCS championship game — which, of course, was held at the Rose Bowl that season. We felt we’d earned the right to play Miami, but were bypassed for Nebraska, which was behind us in the polls and hadn’t even played for its conference championship after being pounded by Colorado (which we would defeat in the Fiesta Bowl).

That was my final chance at a Rose Bowl dream, and it was taken from me.

The irony, though — and I’ve said this before, and a lot of my former teammates have given me grief for it — is the way the story played out couldn’t have been more perfect for Oregon. The whole country thought we should’ve been in that national title game, and the fact that we weren’t created some buzz. It drew in viewers that otherwise wouldn’t have been there. It created fans. By us playing in the Fiesta Bowl and winning in such blowout fashion, we not only made new temporary Ducks supporters, but kept a hell of a lot of them, as well.

Had we gone to the Rose Bowl and played that mighty Miami team, the fairy tale ending might have changed. We would’ve been up against a team that wound up having six guys drafted in the first round. We had one of the best draft years in Oregon history that season, and had six guys drafted total.

If we play that Miami team 10 times, I honestly think we win three of them — not unlike how Ohio State eventually beat them the following year. Had we played them and lost? The national narrative may have changed, at least in the short term, but what we helped put in place for the long term still would have been there.

When I first got to Eugene in 1997, I was part of a rag-tag group of freshmen that, for whatever reason, ruffled a lot of feathers. We weren’t OK with being average, and we let everyone know it. When we talked about things like winning national championships and going to the Rose Bowl, people sort of dismissed us. That was fine by us.

Here was a bunch of two-and-three-star recruits who came in and — I think it’s fair to say — completely changed the program. To go from a six-win season in 1997 to being the first 11-win team in school history our senior year? It was incredible, even if we ultimately came up short of our goal. Throughout that process, we experienced something few people ever have the chance to: building something successful, strong, and permanent.

(Paul Warner, AP)

Now, here’s my NFL story …

In 2002, the Detroit Lions selected me at No. 3 overall. The four years I spent there absolutely crushed me. By the time I left, I was a shell of the player I once was. Here’s an example of how broken things were by the end.

I remember walking into the office of then head coach Steve Mariucci and telling him, “I need you to give me permission to throw the ball down the field.” I’d never felt so down. At that point, I was just searching — grasping — for some kind of support.

“Why do you need permission?” he asked.

“I’m afraid to make a mistake,” I said. “You tell me every day, if it’s close, check it down … and I’ve gotten into a rhythm where all I do is check it down, and I’m afraid to throw it down the field.”

He got up, went to his closet, grabbed a toothbrush, and started brushing his teeth. Then he walked towards the door, and said, “I have to go do some interviews. I’ll be back. If you want to come back later, we can talk.”

He just left.

That was at the very end, when things had all but collapsed around me. Mariucci was a good guy who was trying to save his job, but when one of my teammates went out and said I was the reason our coach got fired, it created a situation where I just imploded mentally. I couldn’t handle it.

This wasn’t football. This wasn’t team. This wasn’t fun.

Through the gentle nudging of general manager Matt Millen — who was, in my opinion, one of the only stand-up guys in that organization — I spent a lot of time with a sports psychologist, trying to figure out how to get my confidence back. In the NFL (and especially at the quarterback position), if you don’t have confidence, you’re done.

There are 100 guys out there who can throw a comeback route, and 100 more who can throw a post. But there are only a handful of quarterbacks who can have the route picked off, then come back and throw it again. Who can get knocked down or get hit in the teeth … and throw it again.

That, to me, is the difference between making it to the NFL, and being great in the NFL.

I’m sometimes asked if I was put in an unfair position in Detroit. My answer is always immediate and the same: No. Saying so implies I was the only one in that kind of a position. Welcome to the NFL. Pick a year, and I’ll give you five guys who were in the same type of spot I was. For all of my prior success — all the balls I had bounce my way through college — I wasn’t prepared to deal with it when things no longer went my way.

If we’re being honest, not a lot of people are.

Toward the end of my tenure in Detroit, Millen and I sat down and talked. He asked me flat out if I wanted to be there anymore. I told him I didn’t know. He’d just brought in Mike Martz — at the time one of the NFL’s most celebrated offensive gurus, just a few years removed from having helped take the Rams’ “Greatest Show on Turf” to the Super Bowl. It was Millen’s belief that Mike could get me back on track. After Matt, I spoke with the new head coach, Rod Marinelli.

“Look, Rod,” I said. “If you want me to be here, I will be here, because I respect you, and I respect Matt. But with the exception of one or two guys in that locker room … the rest of them can go to hell.”

At that point, I felt like I’d given everything, had sacrificed for my teammates, and all they’d done was hang me out to dry. The day everything happened with Dre’ Bly — the scapegoat saga — only two people came up to me and said anything: One guy in the locker room, and the chef in the cafeteria.

My message to Rod was, “I’ll play for you. I respect the fact that you can sit down and have an honest conversation with me. But you need to know what’s happened up to this point.”

What I wanted, like any player does, was options. So when I met with Nick Saban — I remember this very clearly — we sat down at the dinner table and he said, “We traded a second-round pick for Daunte Culpepper. We’re going to trade a fifth-round pick for you. I don’t care what we’re paying him; I don’t care what were paying you. He’s going to get the first-team reps, you’re going to get the second-team reps. If he plays better than you, he’s going to play; if you play better than him, you’re going to play. Can you handle that?”

I said, ‘‘That’s all I’ve been looking for.” After that, I told Matt I was going to Miami. I still talk to Matt Millen to this day. He’s a fantastic, wonderful guy. But it was time for both sides to part ways.

As it turns out, Miami was where I met the two guys I say were most like me — the coaches I felt most connected to in the league: Jason Garrett and Mike Mularkey. They were tremendous football minds and even better people. Before Miami, I was as low as I’d ever been mentally. I had to spend a good amount of time trying to get back to who I was, and those guys were instrumental in that.

Jason and Mike understood life in ways a lot of people don’t. They grasped the importance of putting in work on the football field, but they also understood where football fell on the totem pole of life. What they had was perspective. Looking back, I see it as one of the greatest gifts football has given me.

As for Saban, he and I actually had a really good relationship. Many people think of him as a little dictator, but we got along really well. He could be honest with me, and I would listen. After four years of having something said to my face and different things said behind closed doors, all I wanted was a coach who told me where I stood. Nick gave that to me.

Part of me thinks that had Nick stayed in Miami, and not left for Alabama, I’d have stayed there as well. There was a sense of stability about Saban’s stint in Miami. In another life, it might’ve been the place where I really regained my football footing. Sadly, this one had other ideas.

(Paul Sancya, AP)

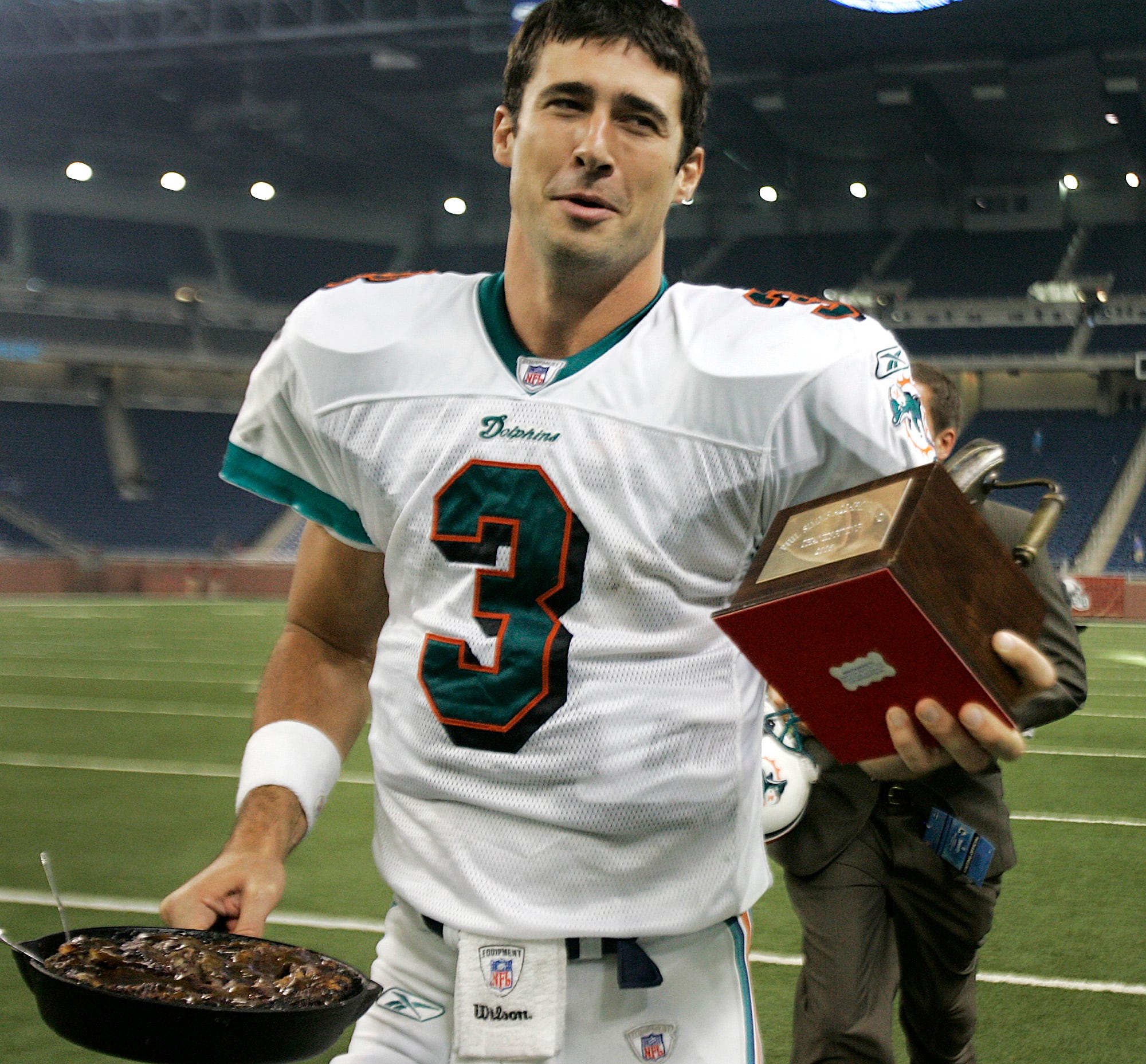

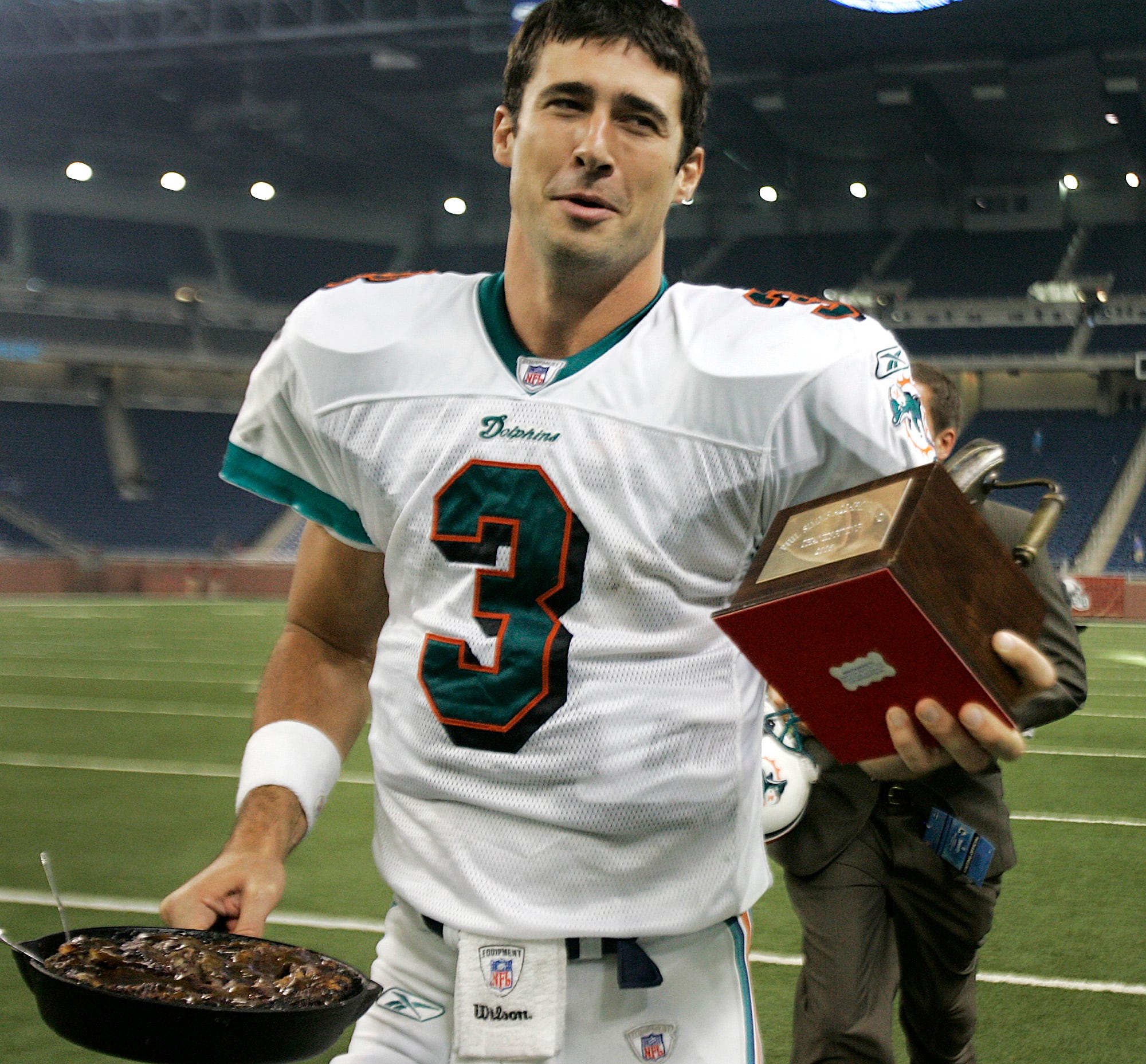

Thanksgiving Day, 2006. I’m with the Dolphins, and we’re back in Detroit to face the Lions. It was the most gratifying day of my NFL career.

213 yards. Three touchdowns. And, more importantly, a win.

Afterward, I stayed in Detroit and flew back to Portland to be with my family. On my ride to airport, I heard one of the sports-talk guys say, “Well, he only threw for 220 yards and three touchdowns … it’s not like he threw for 350.”

Even in victory, even though I knew I’d only thrown one pass in the fourth because we were beating them so badly, they found a way to try to bring me down.

So yeah, you can say that was a satisfying day. It’s impossible to quantify what a performance like that can do for a quarterback’s confidence. For the first time in what felt like ages, I’d proved to people — and to myself — that I could still play this game, and play it at a high level.

My reputation as a quarterback was never about my arm. I was never a fast runner, nor adept at throwing lasers into tight coverage. My strength lay in my ability to read a situation, process the information, and get the ball where it needed to go — all while getting my teammates to follow my lead.

So many times at Oregon we’d be down in the fourth, and I’d walk into that huddle and say, “Okay, let’s go win.” And no one doubted it. That’s who I was. That’s what I did. That’s what we did.

But the time during which I started playing better in Miami was also when I started asking myself: “What is this world I’m living in?” Knowing I wasn’t defined by football had long been a kind of psychological cornerstone for me. I never felt football defined me. I was a good person — with many interests beyond the gridiron — who happened to play football.

Truth told, that feeling took away a little bit of that edge. As soon as football no longer defines you, the consequences of losing aren’t as dire. When I started to shift my mindset, and start believing in myself as a person and a player again, was when my motivation started to disintegrate. Football no longer was the centerpiece of my life.

So many guys play the game with a boulder-sized chip on their shoulder, where playing becomes a matter of life and death. For some of them, it is. This is their ticket. It’s all they know or care to know. I believe that, at a certain point, my overriding desire to keep life in perspective prevented me from taking that diehard approach.

I definitely had it when I was drafted, but as soon as you realize there’s something more important out there, you can only get kicked in the teeth so many times before you say, “You know what? It’s been fun. Let’s go try something else.”

Then, I went to Atlanta.

Fortunately — or unfortunately … however you want to look at it — all I’d been through to that point in my career helped me prepare for the absolute mess that was the Falcons.

When I first got word of Michael Vick’s dog-fighting scandal, I was in central Oregon, about a week before training camp started. I turned on the TV and saw Vick getting taken away in handcuffs. The phone rang, and I picked up.

“Are you ready?” the voice on the other end said.

I was ready. Or at least I thought I was.

That team had a head coach, Bobby Petrino, who was so ill-equipped to coach an NFL team, it was laughable. If anybody challenged him, or suggested something different, the person was cast away. It was an unhealthy environment from the get-go, and it wouldn’t get any better.

If you go back and look at the first four games of the 2007 season — my only one in Atlanta — I actually played really good football. There were a couple games in a row where I was putting up great numbers, but we couldn’t find a way to win. And as anyone who knows the NFL will tell you, when you lose, things change. Even if perception doesn’t match reality.

I get asked about Michael Vick a lot. Strange as it sounds, that relationship was one of the bright spots during my time with the Falcons. I really liked Mike, and was thrilled to see him turn his life around. If you were to meet him in passing, you’d probably say he’s a bit standoffish. Maybe even a little arrogant. But he had to be. For as much as I felt my life was bubbled, his life was ten times more chaotic — the pressure, the scrutiny, the endless questions — than most other players. If you actually took the time to sit down and talk to him, one on one, you knew he was a good person.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t root for Vick every time I saw him on the field. How many people, halfway through their career, and with as much baggage as he carried, can completely reinvent themselves like that? Early on, he really was the last one out on the practice field — shoes untied and chin strap undone — and the first one out the door. To go from that to learning how to be a true professional and great locker room guy is hard to do, and I give the man a ton of credit. In the end, he truly became the person we all knew was there underneath the armored shell.

My last stop in the NFL was New Orleans.

Throughout my time in the league, I saw teammates enroll their kids in school, wherever we were playing, only to re-enroll them where they lived full time after winter break. When I had a family, I knew that wasn’t the life I wanted to give my kids. Part of what made my upbringing so great is I’m still friends with kids I went to grade school with. That’s my crew. If you’re moving from place to place, constantly picking up and setting down in other places, how can you build long-term relationships?

When I signed with the Saints, we’d just had out first son. I went out to training camp, and my wife and son came out a week later. After the first round of cuts, I was told I was safe.

So we started unpacking. Two days later, I was cut. It’s the nature of the business. One of the things I’d come to learn about myself was how much I valued stability. Prior to that training camp, I told my wife, “The next time I get released, we’re going home. We’re going back to Oregon, we’re setting down roots, and we’re starting the next part of our life.”

There’s something special about being able to take your kids to their grandparents’ house, to have their aunts and uncles around the Thanksgiving table. For as much as this country loves the sport of football — and I include myself in that — there are thousands of things that are more important. I think we lose sight of that sometimes. In our race to win on the field, we forget about the human beings who make it all happen. About the people dealing with their own struggles, far away from the glam and glitz of the gridiron.

I found something more important, and I have absolutely no regrets.

Everyone says when you retire, you miss the locker room the most. The only place I feel that way about is Oregon. That’s the locker room I miss.

(AP)

When I left college, there was still a purity to the game of football; a feeling of fun and camaraderie that couldn’t be replicated anywhere else. I knew when I got to the NFL that it was going to be a business — sometimes even a brutal one — but hey, you got paid to play the game, right? That sounded good to me.

What they don’t tell you is, because of that, all the things that made the game fun — the togetherness, the sense of shared purpose — disappear. Camaraderie gives way to a distrust of one’s own teammates. You no longer look at them as brothers in arms; you look at them like a guy who’s trying to take your job. That feeling of family, of everyone living the same lives, was gone. In its place came one of the coldest realities a human can know: having to grow up.

This manifested itself in numerous ways. You saw it in the relationships you had with the team’s medical staff. That trust you once had, that they’re looking out for your best interest, is subsumed by the fact that they’re working for someone who stands to benefit most from your being on the field.

This creates an environment where the majority of NFL players, if given the opportunity, will play in a game even if they’re advised not to. If they don’t, they might be putting their jobs at risk. It’s not like you can take a medical leave; the season — and the team — are built to move on without you, if they have to. It is the job of the coach and front office to win games. If they give someone else the opportunity to do the job you were doing, and if that player does it well, you may find yourself staring at a pink slip.

The approach is inherently shortsighted, at least when it comes to the welfare of the athletes. Even today, I wake up with bone spurs in my ankles, fewer ligaments in my shoulder, and disc issues in my back. And I got out relatively unscathed.

Did I know what I was getting into when I left college? I can’t say I did. People told me, “Things are going to be different. The NFL is a business,” but I had no idea of the full magnitude of the difference. With the exception of maybe five guys on each team — those with contracts weighing heavily on the salary cap — most players are completely expendable. There’s no GM that says, “You know what? He’s a good guy. I’m going to hang onto him,” if someone else out there can do your job for a fraction less.

Then there’s how players sometimes act because of what they’re asked to be on the field. The sport — its producers, players, and consumers — have come to expect a certain level of aggression. Everyone wants their players to be destructive on the field, but in order to sell Sunday product, it has to be manufactured from Monday through Saturday.

The expectations that your favorite player will be a monster on Sundays and a saint the rest of the week — well, that’s not how human nature really works. You’re going to be what you’ve trained to become. So it’s outright hypocritical for people to applaud and glorify the violent things someone does on the football field, only to be surprised and appalled at the reprehensible things they do off of it.

As for the rhetoric that comes from the NFL about player health and safety? It’s all a bunch of crap. Roger Goodell has made no bones about his duty to “protect the shield.” That means protecting the brand — one that’s become one of the biggest cash cows anywhere in the world. If protecting players is at odds with that, so be it.

Everyone in the NFL has watched someone go in for surgery on Monday, and strap on the pads that Sunday. Everyone has either been hit so hard the world spins, or seen it happen to someone else. We’ve all been there. And the fact that we’re expected to go back in — at the risk of losing our jobs — creates a pretty lose-lose situation.

(David Drapkin, AP)

Yet for all the quips and qualms I might have about how the NFL is run, I can’t deny how much football has given me. And I’m not just talking about the financial aspect. There are things football can teach you that no other sport can. This is a game, after all, where another person can legally put their helmet into your sternum. You have a choice: Do I get up? Or do I stay down? It’s a lesson that simply can’t be replicated — physically — in other sports. Which is why I’m always so conflicted when I talk about the NFL. Because this game has given me so much. And for that, I love it.

At some point, I want my children to experience football. I think I do, anyway. In the end, I’d probably ultimately let them. After lots of discussion, of course — and honest ones — because the inherent risks in the game are real.

During my final preseason game with the Saints, I went flying headfirst to try and get a first down. I was doing my job. My helmet was smashed into the ground. When I looked up and saw the trainers, I asked them how they got there so fast. “Joey,” they said. “We’ve been here a couple minutes.” Concussions happen. Preseason, regular season, postseason. They happen.

After every game I’d go home and sit on the couch. Around 9 p.m. — like clockwork — I’d come down with a splitting headache. Was that getting my bell rung, or more the toll a career in football had taken? I still don’t have an answer to that, though I often wonder.

Football is a lot of things to a lot of people. What it’s not, however, is the glorious gladiator life painted for people to see. It’s painful. It’s nerve-wracking. Left unchecked, it can be destructive to a lot of things in your life. But people are willing to get paid a lot of money for that sacrifice. In the end, it’s a choice we all have to make. I’m just glad I made the choices I made, and when I made them.

It’s interesting, being on the other side of things now, in the media, where you’re told to be critical of the guys who are out there playing. Having had time to watch games from the outside, or in the company of regular fans, it’s interesting how warped — for lack of a better word — people’s perception of success is. It seems like the belief is that, if you end your career as a Hall of Famer, you were automatically successful. If you don’t, then you weren’t.

To me, my career was a huge success. Not so much because of what I achieved or didn’t achieve, but in how it set me up for the rest of my life. In my mind, the only time you can view someone’s football career as a failure is if they didn’t use their success as a platform to better the world around them.

In 2003, I launched the Harrington Family Foundation. The goal of the organization is to find young leaders and give them the tools they need to develop that leadership. We give out “Community Quarterback” scholarships — four years, and to any four-year school in Oregon — to kids we view as future leaders of the state. We network on their behalf, introducing them to the people who can help further their dreams. The typical kid we work with isn’t a 4.0 student. The students I want? Maybe they get a C in their English class, because it’s not their passion. But they have ideas. They have the ability to think critically. They can gather, and lead, in ways other kids can’t.

This is my passion, and it’s where I truly believe my NFL career was supposed to lead me to. As much as I love the game of football, if I’m truly living by the definition of what I view success to be, then I want to be — and need to be — involved with my kids’ lives in a way being in the media doesn’t allow.

My next goal? To raise a family that’s cohesive. To be present in the lives of my wife and kids, so when they look back 20 years from now, they have fond memories of their dad and husband.

I was recently asked if I would give up everything I did professionally for a shot at the Rose Bowl. I won’t lie, I had to think about it pretty hard, but ultimately my answer was no. Not because football no longer means that much to me, but because it taught me what truly means the most.

Football — those experiences — shaped my life, and shaped the man I’ve become. It helped me create a solid financial footing, and opened doors that otherwise wouldn’t have been there. Even if the path wasn’t always what I predicted, football helped bring me where I am. And I love — truly love — where I am.

"Harrington's career in Detroit was largely unsuccessful. Front office mismanagement, woeful offensive line protection, lack of talent at other skill positions, and an erratic philosophical change in the team's identity to a conservative West Coast Offense (WCO) oriented attack under Head Coach Steve Mariucci may have played a factor in Harrington not realizing his potential professionally.

Despite his difficult times in Detroit, he remained unwaveringly optimistic and was thus dubbed "Joey Blue-Skies" and "Joey Sunshine" by sarcastic Lions' fans and beat writers who grew tired of his predictable post-game commentary as the losses continued to mount."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joey_Harrington

Sounds pretty close to the travails of Sam Bradford while with the Rams. Harrington then went on to play for the Dolphins, Falcons, and Saints. He talks about his career in the article below.

******************************************************************************

https://thecauldron.si.com/despite-...-career-was-a-success-179aeca1b1e7#.kmrkcy287

(AP)

Despite What You May Think, My NFL Career Was A Success

There were times — a good majority of my career — when I didn’t play well, but the ups and downs helped set me up in life.

By Joey Harrington

Seven seasons have come and gone since I retired from the NFL. I went out on my terms, when I was ready. I fulfilled all I set out to do.

At least at the pro level.

If you find that curious, I’m going to explain what happened at every step in my career, and why — regardless of outside perceptions — I think it was a rousing success, but first let me let you in on a little secret: My biggest football dream growing up was to play in the Rose Bowl, not in the NFL.

Sadly, it’s the one thing I was never able to make happen.

I was 11 years old when my dad first took me to Pasadena. It was Bo Schembechler’s last game — Michigan vs. USC — and we’d arrived hours before kickoff. We walked around and looked at all the plaques on the wall outside the Rose Bowl — the ones that list all the previous MVPs.

That’s when I did the math.

“Dad, that one’s going to be me,” I said, looking at the still-empty space for the year 2000. “Right there. That one.”

When that year finally came around, my junior year at Oregon, I reminded him again before the annual Civil War game against Oregon State. We were going to Pasadena, I told him. I wound up throwing five picks in a 23–13 loss. Our shot at the Rose Bowl was gone.

Making that game was always my biggest football ambition. Not to improve my draft stock, not to be a pro football Hall of Famer. Play college football, go to the Rose Bowl, set myself up for success and life, and have fun. That was it.

When I came back for my senior year, we had the best regular season (to that point) in Oregon history, but were left out of the BCS championship game — which, of course, was held at the Rose Bowl that season. We felt we’d earned the right to play Miami, but were bypassed for Nebraska, which was behind us in the polls and hadn’t even played for its conference championship after being pounded by Colorado (which we would defeat in the Fiesta Bowl).

That was my final chance at a Rose Bowl dream, and it was taken from me.

The irony, though — and I’ve said this before, and a lot of my former teammates have given me grief for it — is the way the story played out couldn’t have been more perfect for Oregon. The whole country thought we should’ve been in that national title game, and the fact that we weren’t created some buzz. It drew in viewers that otherwise wouldn’t have been there. It created fans. By us playing in the Fiesta Bowl and winning in such blowout fashion, we not only made new temporary Ducks supporters, but kept a hell of a lot of them, as well.

Had we gone to the Rose Bowl and played that mighty Miami team, the fairy tale ending might have changed. We would’ve been up against a team that wound up having six guys drafted in the first round. We had one of the best draft years in Oregon history that season, and had six guys drafted total.

If we play that Miami team 10 times, I honestly think we win three of them — not unlike how Ohio State eventually beat them the following year. Had we played them and lost? The national narrative may have changed, at least in the short term, but what we helped put in place for the long term still would have been there.

When I first got to Eugene in 1997, I was part of a rag-tag group of freshmen that, for whatever reason, ruffled a lot of feathers. We weren’t OK with being average, and we let everyone know it. When we talked about things like winning national championships and going to the Rose Bowl, people sort of dismissed us. That was fine by us.

Here was a bunch of two-and-three-star recruits who came in and — I think it’s fair to say — completely changed the program. To go from a six-win season in 1997 to being the first 11-win team in school history our senior year? It was incredible, even if we ultimately came up short of our goal. Throughout that process, we experienced something few people ever have the chance to: building something successful, strong, and permanent.

(Paul Warner, AP)

Now, here’s my NFL story …

In 2002, the Detroit Lions selected me at No. 3 overall. The four years I spent there absolutely crushed me. By the time I left, I was a shell of the player I once was. Here’s an example of how broken things were by the end.

I remember walking into the office of then head coach Steve Mariucci and telling him, “I need you to give me permission to throw the ball down the field.” I’d never felt so down. At that point, I was just searching — grasping — for some kind of support.

“Why do you need permission?” he asked.

“I’m afraid to make a mistake,” I said. “You tell me every day, if it’s close, check it down … and I’ve gotten into a rhythm where all I do is check it down, and I’m afraid to throw it down the field.”

He got up, went to his closet, grabbed a toothbrush, and started brushing his teeth. Then he walked towards the door, and said, “I have to go do some interviews. I’ll be back. If you want to come back later, we can talk.”

He just left.

That was at the very end, when things had all but collapsed around me. Mariucci was a good guy who was trying to save his job, but when one of my teammates went out and said I was the reason our coach got fired, it created a situation where I just imploded mentally. I couldn’t handle it.

This wasn’t football. This wasn’t team. This wasn’t fun.

Through the gentle nudging of general manager Matt Millen — who was, in my opinion, one of the only stand-up guys in that organization — I spent a lot of time with a sports psychologist, trying to figure out how to get my confidence back. In the NFL (and especially at the quarterback position), if you don’t have confidence, you’re done.

There are 100 guys out there who can throw a comeback route, and 100 more who can throw a post. But there are only a handful of quarterbacks who can have the route picked off, then come back and throw it again. Who can get knocked down or get hit in the teeth … and throw it again.

That, to me, is the difference between making it to the NFL, and being great in the NFL.

I’m sometimes asked if I was put in an unfair position in Detroit. My answer is always immediate and the same: No. Saying so implies I was the only one in that kind of a position. Welcome to the NFL. Pick a year, and I’ll give you five guys who were in the same type of spot I was. For all of my prior success — all the balls I had bounce my way through college — I wasn’t prepared to deal with it when things no longer went my way.

If we’re being honest, not a lot of people are.

Toward the end of my tenure in Detroit, Millen and I sat down and talked. He asked me flat out if I wanted to be there anymore. I told him I didn’t know. He’d just brought in Mike Martz — at the time one of the NFL’s most celebrated offensive gurus, just a few years removed from having helped take the Rams’ “Greatest Show on Turf” to the Super Bowl. It was Millen’s belief that Mike could get me back on track. After Matt, I spoke with the new head coach, Rod Marinelli.

“Look, Rod,” I said. “If you want me to be here, I will be here, because I respect you, and I respect Matt. But with the exception of one or two guys in that locker room … the rest of them can go to hell.”

At that point, I felt like I’d given everything, had sacrificed for my teammates, and all they’d done was hang me out to dry. The day everything happened with Dre’ Bly — the scapegoat saga — only two people came up to me and said anything: One guy in the locker room, and the chef in the cafeteria.

My message to Rod was, “I’ll play for you. I respect the fact that you can sit down and have an honest conversation with me. But you need to know what’s happened up to this point.”

What I wanted, like any player does, was options. So when I met with Nick Saban — I remember this very clearly — we sat down at the dinner table and he said, “We traded a second-round pick for Daunte Culpepper. We’re going to trade a fifth-round pick for you. I don’t care what we’re paying him; I don’t care what were paying you. He’s going to get the first-team reps, you’re going to get the second-team reps. If he plays better than you, he’s going to play; if you play better than him, you’re going to play. Can you handle that?”

I said, ‘‘That’s all I’ve been looking for.” After that, I told Matt I was going to Miami. I still talk to Matt Millen to this day. He’s a fantastic, wonderful guy. But it was time for both sides to part ways.

As it turns out, Miami was where I met the two guys I say were most like me — the coaches I felt most connected to in the league: Jason Garrett and Mike Mularkey. They were tremendous football minds and even better people. Before Miami, I was as low as I’d ever been mentally. I had to spend a good amount of time trying to get back to who I was, and those guys were instrumental in that.

Jason and Mike understood life in ways a lot of people don’t. They grasped the importance of putting in work on the football field, but they also understood where football fell on the totem pole of life. What they had was perspective. Looking back, I see it as one of the greatest gifts football has given me.

As for Saban, he and I actually had a really good relationship. Many people think of him as a little dictator, but we got along really well. He could be honest with me, and I would listen. After four years of having something said to my face and different things said behind closed doors, all I wanted was a coach who told me where I stood. Nick gave that to me.

Part of me thinks that had Nick stayed in Miami, and not left for Alabama, I’d have stayed there as well. There was a sense of stability about Saban’s stint in Miami. In another life, it might’ve been the place where I really regained my football footing. Sadly, this one had other ideas.

(Paul Sancya, AP)

Thanksgiving Day, 2006. I’m with the Dolphins, and we’re back in Detroit to face the Lions. It was the most gratifying day of my NFL career.

213 yards. Three touchdowns. And, more importantly, a win.

Afterward, I stayed in Detroit and flew back to Portland to be with my family. On my ride to airport, I heard one of the sports-talk guys say, “Well, he only threw for 220 yards and three touchdowns … it’s not like he threw for 350.”

Even in victory, even though I knew I’d only thrown one pass in the fourth because we were beating them so badly, they found a way to try to bring me down.

So yeah, you can say that was a satisfying day. It’s impossible to quantify what a performance like that can do for a quarterback’s confidence. For the first time in what felt like ages, I’d proved to people — and to myself — that I could still play this game, and play it at a high level.

My reputation as a quarterback was never about my arm. I was never a fast runner, nor adept at throwing lasers into tight coverage. My strength lay in my ability to read a situation, process the information, and get the ball where it needed to go — all while getting my teammates to follow my lead.

So many times at Oregon we’d be down in the fourth, and I’d walk into that huddle and say, “Okay, let’s go win.” And no one doubted it. That’s who I was. That’s what I did. That’s what we did.

But the time during which I started playing better in Miami was also when I started asking myself: “What is this world I’m living in?” Knowing I wasn’t defined by football had long been a kind of psychological cornerstone for me. I never felt football defined me. I was a good person — with many interests beyond the gridiron — who happened to play football.

Truth told, that feeling took away a little bit of that edge. As soon as football no longer defines you, the consequences of losing aren’t as dire. When I started to shift my mindset, and start believing in myself as a person and a player again, was when my motivation started to disintegrate. Football no longer was the centerpiece of my life.

So many guys play the game with a boulder-sized chip on their shoulder, where playing becomes a matter of life and death. For some of them, it is. This is their ticket. It’s all they know or care to know. I believe that, at a certain point, my overriding desire to keep life in perspective prevented me from taking that diehard approach.

I definitely had it when I was drafted, but as soon as you realize there’s something more important out there, you can only get kicked in the teeth so many times before you say, “You know what? It’s been fun. Let’s go try something else.”

Then, I went to Atlanta.

Fortunately — or unfortunately … however you want to look at it — all I’d been through to that point in my career helped me prepare for the absolute mess that was the Falcons.

When I first got word of Michael Vick’s dog-fighting scandal, I was in central Oregon, about a week before training camp started. I turned on the TV and saw Vick getting taken away in handcuffs. The phone rang, and I picked up.

“Are you ready?” the voice on the other end said.

I was ready. Or at least I thought I was.

That team had a head coach, Bobby Petrino, who was so ill-equipped to coach an NFL team, it was laughable. If anybody challenged him, or suggested something different, the person was cast away. It was an unhealthy environment from the get-go, and it wouldn’t get any better.

If you go back and look at the first four games of the 2007 season — my only one in Atlanta — I actually played really good football. There were a couple games in a row where I was putting up great numbers, but we couldn’t find a way to win. And as anyone who knows the NFL will tell you, when you lose, things change. Even if perception doesn’t match reality.

I get asked about Michael Vick a lot. Strange as it sounds, that relationship was one of the bright spots during my time with the Falcons. I really liked Mike, and was thrilled to see him turn his life around. If you were to meet him in passing, you’d probably say he’s a bit standoffish. Maybe even a little arrogant. But he had to be. For as much as I felt my life was bubbled, his life was ten times more chaotic — the pressure, the scrutiny, the endless questions — than most other players. If you actually took the time to sit down and talk to him, one on one, you knew he was a good person.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t root for Vick every time I saw him on the field. How many people, halfway through their career, and with as much baggage as he carried, can completely reinvent themselves like that? Early on, he really was the last one out on the practice field — shoes untied and chin strap undone — and the first one out the door. To go from that to learning how to be a true professional and great locker room guy is hard to do, and I give the man a ton of credit. In the end, he truly became the person we all knew was there underneath the armored shell.

My last stop in the NFL was New Orleans.

Throughout my time in the league, I saw teammates enroll their kids in school, wherever we were playing, only to re-enroll them where they lived full time after winter break. When I had a family, I knew that wasn’t the life I wanted to give my kids. Part of what made my upbringing so great is I’m still friends with kids I went to grade school with. That’s my crew. If you’re moving from place to place, constantly picking up and setting down in other places, how can you build long-term relationships?

When I signed with the Saints, we’d just had out first son. I went out to training camp, and my wife and son came out a week later. After the first round of cuts, I was told I was safe.

So we started unpacking. Two days later, I was cut. It’s the nature of the business. One of the things I’d come to learn about myself was how much I valued stability. Prior to that training camp, I told my wife, “The next time I get released, we’re going home. We’re going back to Oregon, we’re setting down roots, and we’re starting the next part of our life.”

There’s something special about being able to take your kids to their grandparents’ house, to have their aunts and uncles around the Thanksgiving table. For as much as this country loves the sport of football — and I include myself in that — there are thousands of things that are more important. I think we lose sight of that sometimes. In our race to win on the field, we forget about the human beings who make it all happen. About the people dealing with their own struggles, far away from the glam and glitz of the gridiron.

I found something more important, and I have absolutely no regrets.

Everyone says when you retire, you miss the locker room the most. The only place I feel that way about is Oregon. That’s the locker room I miss.

(AP)

When I left college, there was still a purity to the game of football; a feeling of fun and camaraderie that couldn’t be replicated anywhere else. I knew when I got to the NFL that it was going to be a business — sometimes even a brutal one — but hey, you got paid to play the game, right? That sounded good to me.

What they don’t tell you is, because of that, all the things that made the game fun — the togetherness, the sense of shared purpose — disappear. Camaraderie gives way to a distrust of one’s own teammates. You no longer look at them as brothers in arms; you look at them like a guy who’s trying to take your job. That feeling of family, of everyone living the same lives, was gone. In its place came one of the coldest realities a human can know: having to grow up.

This manifested itself in numerous ways. You saw it in the relationships you had with the team’s medical staff. That trust you once had, that they’re looking out for your best interest, is subsumed by the fact that they’re working for someone who stands to benefit most from your being on the field.

This creates an environment where the majority of NFL players, if given the opportunity, will play in a game even if they’re advised not to. If they don’t, they might be putting their jobs at risk. It’s not like you can take a medical leave; the season — and the team — are built to move on without you, if they have to. It is the job of the coach and front office to win games. If they give someone else the opportunity to do the job you were doing, and if that player does it well, you may find yourself staring at a pink slip.

The approach is inherently shortsighted, at least when it comes to the welfare of the athletes. Even today, I wake up with bone spurs in my ankles, fewer ligaments in my shoulder, and disc issues in my back. And I got out relatively unscathed.

Did I know what I was getting into when I left college? I can’t say I did. People told me, “Things are going to be different. The NFL is a business,” but I had no idea of the full magnitude of the difference. With the exception of maybe five guys on each team — those with contracts weighing heavily on the salary cap — most players are completely expendable. There’s no GM that says, “You know what? He’s a good guy. I’m going to hang onto him,” if someone else out there can do your job for a fraction less.

Then there’s how players sometimes act because of what they’re asked to be on the field. The sport — its producers, players, and consumers — have come to expect a certain level of aggression. Everyone wants their players to be destructive on the field, but in order to sell Sunday product, it has to be manufactured from Monday through Saturday.

The expectations that your favorite player will be a monster on Sundays and a saint the rest of the week — well, that’s not how human nature really works. You’re going to be what you’ve trained to become. So it’s outright hypocritical for people to applaud and glorify the violent things someone does on the football field, only to be surprised and appalled at the reprehensible things they do off of it.

As for the rhetoric that comes from the NFL about player health and safety? It’s all a bunch of crap. Roger Goodell has made no bones about his duty to “protect the shield.” That means protecting the brand — one that’s become one of the biggest cash cows anywhere in the world. If protecting players is at odds with that, so be it.

Everyone in the NFL has watched someone go in for surgery on Monday, and strap on the pads that Sunday. Everyone has either been hit so hard the world spins, or seen it happen to someone else. We’ve all been there. And the fact that we’re expected to go back in — at the risk of losing our jobs — creates a pretty lose-lose situation.

(David Drapkin, AP)

Yet for all the quips and qualms I might have about how the NFL is run, I can’t deny how much football has given me. And I’m not just talking about the financial aspect. There are things football can teach you that no other sport can. This is a game, after all, where another person can legally put their helmet into your sternum. You have a choice: Do I get up? Or do I stay down? It’s a lesson that simply can’t be replicated — physically — in other sports. Which is why I’m always so conflicted when I talk about the NFL. Because this game has given me so much. And for that, I love it.

At some point, I want my children to experience football. I think I do, anyway. In the end, I’d probably ultimately let them. After lots of discussion, of course — and honest ones — because the inherent risks in the game are real.

During my final preseason game with the Saints, I went flying headfirst to try and get a first down. I was doing my job. My helmet was smashed into the ground. When I looked up and saw the trainers, I asked them how they got there so fast. “Joey,” they said. “We’ve been here a couple minutes.” Concussions happen. Preseason, regular season, postseason. They happen.

After every game I’d go home and sit on the couch. Around 9 p.m. — like clockwork — I’d come down with a splitting headache. Was that getting my bell rung, or more the toll a career in football had taken? I still don’t have an answer to that, though I often wonder.

Football is a lot of things to a lot of people. What it’s not, however, is the glorious gladiator life painted for people to see. It’s painful. It’s nerve-wracking. Left unchecked, it can be destructive to a lot of things in your life. But people are willing to get paid a lot of money for that sacrifice. In the end, it’s a choice we all have to make. I’m just glad I made the choices I made, and when I made them.

It’s interesting, being on the other side of things now, in the media, where you’re told to be critical of the guys who are out there playing. Having had time to watch games from the outside, or in the company of regular fans, it’s interesting how warped — for lack of a better word — people’s perception of success is. It seems like the belief is that, if you end your career as a Hall of Famer, you were automatically successful. If you don’t, then you weren’t.

To me, my career was a huge success. Not so much because of what I achieved or didn’t achieve, but in how it set me up for the rest of my life. In my mind, the only time you can view someone’s football career as a failure is if they didn’t use their success as a platform to better the world around them.

In 2003, I launched the Harrington Family Foundation. The goal of the organization is to find young leaders and give them the tools they need to develop that leadership. We give out “Community Quarterback” scholarships — four years, and to any four-year school in Oregon — to kids we view as future leaders of the state. We network on their behalf, introducing them to the people who can help further their dreams. The typical kid we work with isn’t a 4.0 student. The students I want? Maybe they get a C in their English class, because it’s not their passion. But they have ideas. They have the ability to think critically. They can gather, and lead, in ways other kids can’t.

This is my passion, and it’s where I truly believe my NFL career was supposed to lead me to. As much as I love the game of football, if I’m truly living by the definition of what I view success to be, then I want to be — and need to be — involved with my kids’ lives in a way being in the media doesn’t allow.

My next goal? To raise a family that’s cohesive. To be present in the lives of my wife and kids, so when they look back 20 years from now, they have fond memories of their dad and husband.

I was recently asked if I would give up everything I did professionally for a shot at the Rose Bowl. I won’t lie, I had to think about it pretty hard, but ultimately my answer was no. Not because football no longer means that much to me, but because it taught me what truly means the most.

Football — those experiences — shaped my life, and shaped the man I’ve become. It helped me create a solid financial footing, and opened doors that otherwise wouldn’t have been there. Even if the path wasn’t always what I predicted, football helped bring me where I am. And I love — truly love — where I am.