- Joined

- Aug 11, 2010

- Messages

- 9,997

Cooper Kupp's unique training approach - Sports Illustrated

How the unlikely star turned in a historic season

Cooper Kupp’s Approach to Greatness

An offseason spent in a kind of scientific exploration of what drives great receiver play led to a historical year from an unlikely superstar.You are reading 1 of 4 free premium articles. Subscribe for unlimited access for just $1. Members log in.

Last spring, before Cooper Kupp turned this season into an argument for NFL history, he moved to a Portland suburb and transformed a backyard tennis court into a barn that doubled as a football laboratory. The goal: Explore the science that drives elite receivers. Dive to subterranean depths. Examine his job, and how to excel even more at it, through analytical concepts of movement. Like dynamic organisms. And uncontrolled manifolds.

In Kupp’s latest football experiment, the dynamic organism was … him. Hence the barn, the space covered and enclosed, the design created by a Rams wideout moonlighting as an interior designer. Kupp had turf put in by the same expert local sports teams used. He added a “curve” treadmill for speedwork; a “timing gate” that measured in seconds and miles per hour, with 20 mph serving as his benchmark; and what’s called a “towing unit,” which he wore while sprinting to add resistance (typically 50% to 75% of his 208 pounds). He didn’t overly complicate this lab with technology, only what he needed, everything deliberate and precise. Like him.

Plan in place and barn constructed, Kupp drilled into as many movement options (wiggles, cuts, stutter steps) as he could develop or hone. The uncontrolled manifolds approach is not just a collection of those movement options, but how his body chooses them—ideally, through subconscious calculations performed by his central nervous system. All must be deeply ingrained so that he can access and deploy them instantly, at any moment. He would take variables—alignments; schemes; skills, weaknesses and body language of defenders; weather; playing surface; and equipment, like which cleats he wore—and input the data he gleaned into an internal calculator.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Kupp would go on to lead the NFL in receptions (145), receiving yards (1,947) and touchdown catches (16). But while the numbers he amassed were borderline historic, what he did mattered far less to him than how he did it. En route to exactly the right place, at precisely the right time, his central nervous system acted like a computer processor, shuffling through his repertoire of movement options. More choices and higher efficiency made Kupp more shifty and more adaptable. When his mental processing sped up, the game slowed down, as he beat not just defenders but entire defensive schemes—and not just with speed, strength or smarts. He upended them through manipulation, with movement, his choices dictating their response.

Start there to understand how Kupp became only the fourth wideout since 1970 to seize the “triple crown” and how he built a plausible argument—one that he himself would never make—for the best season at his position in NFL history. Just don’t define his magical year by the numbers most would slap onto social media alongside a #humbled or a #blessed.

In-depth analysis, unrivaled access. Get SPORTS ILLUSTRATED's best stories every weekday. Sign up now.

Although he had toiled, Kupp doesn’t view this season as 17 happy accidents born from a tireless work ethic. Although genetically gifted, he didn’t overwhelm double teams with physical prowess alone. Although brainy, he refused simple categorization, in particular the notion that he’s “crafty,” a backhanded compliment laced with the implication that he needs to be. There’s truth in every overdone element of his story. Teammates describe him as borderline brilliant. He was discounted; he did run a glacial 40-yard dash at the NFL scouting combine, his time of 4.62 seconds matching that of a speedy punter, Pat O’Donnell of the Bears. But those factors don’t paint Kupp in total.

Instead, his approach—clinical, surgical, endless, compounding, efficient and nerdy as all hell—guided Kupp’s ongoing football evolution. As he transformed from undersized, overlooked prospect to FCS star to mainstay for a perpetual playoff team, it’s how he defined himself, while others consistently mischaracterized him. He needed his science and his natural athletic gifts to morph from a great player into something more.

That’s why Kupp visited Ryan Baugus—founder of Headquarters Wellness—in Wilsonville, Ore., last spring. Why they diagrammed movement options inside a gym, plotting a path toward, Baugus says, “doing something special.” Which explains not only Kupp’s season, but everything he channeled into it.

The journey to Kupp’s slice of NFL history began with a single step, although not an obvious, or metaphorical, one. No, Kupp winnowed his focus to one actual step, his first off the line of scrimmage—football’s most critical movement option.

Kupp also arrived at that specific emphasis last spring, with an assist from Erik Jernstrom, the director of sports performance at EForce Sports in the Portland area. They created an “athletic profile” through a battery of test results and GPS info from the Rams. The data revealed that Kupp reached max velocity sooner than most elite receivers—closer to 25 yards down field, or roughly five yards faster than the norm. They compared how many yards he covered in any one game with how many of those yards he traversed at various percentages (70%, 80%, 90%) of his max velocity. For Kupp to reach top speed sooner and cover greater distance at all percentages, that one small step for one (not-small-anymore) man figured to yield enormous gains.

Then they tailored his training program to address that specific movement, and not for every day or every session, but for every rep. Jernstrom viewed Kupp as a “phenomenal accelerator,” quick, fluid and “aggressive in his bursts.” To upgrade “phenomenal,” they turned to drills, sprints and an ancient Chinese military treatise, The Art of War. The book highlights one relevant combat strategy, the concept of space—creating your own or decreasing your enemy’s—whether applied to the Battle of Normandy or an NFL play. Kupp could create separation, or decrease the cushion cornerbacks desired, if he knew where to go, how to get there and how to deceive them. Which led to the OODA loop, a four-step approach, developed by U.S. fighter pilots—observe, orient, decide and act—to make decisions under extreme pressure with clarity and decisiveness.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Long before Kupp elevated into the rare air breathed by some of the most accomplished receivers in NFL history—marquee names like Jerry Rice, Michael Irvin and Calvin Johnson—he designed his experiments to ensure he would be nothing like them and exactly so. Kupp would never match Rice’s pedigree (“greatest of all time,” he says), Irvin’s competitive nature (“incredible”) or Johnson’s superhero athleticism (“dude is a cyborg, jumping over three people without planting his feet”). But if Kupp dreamed beyond logical expectations, conducted the right tests, worked assiduously to improve and timed everything perfectly, what seemed impossible to most appeared quite possible to him.

After playing the word-association game for three Hall of Famers, Kupp does the same for himself. “I just want to do my job,” he says.

That his job is the same as their jobs never altered Kupp’s ambitions. He simply needed to take a different, well, route to the same place. How else would he approach the game-changing authority of someone like Johnson, who is three inches taller, almost 30 pounds heavier and—no offense to the Kupp family—genetically more gifted in every way?

Rice sprinted up towering hills and caught bricks to harden his hands. Irvin lifted weights in full uniform, helmet atop his head in 100-degree heat and a heavy vest secured around his torso. Johnson partook in Navy SEAL–like drill sessions. To match them, Kupp decided: He would become a dreamer, a transformer and a football scientist, defined not by one part of his approach but by the totality of it. At that point, he needed to answer one question above all: How?

Kupp doesn’t view his improbable season as improbable at all. Instead, he sees more than a dozen factors that coalesced into something greater, just as he intended. Some elements, like work ethic and film study, were standard; others, like first steps and uncontrolled manifolds, scientific; others, like his complete and wide-ranging skill set, developed over seasons, or decades.

The first factor that pointed Kupp toward NFL lore is perhaps the most central of all—and the most unexpected for a football scientist. He grew up in Yakima, a city of 93,000 people roughly 140 miles southeast of Seattle. While best known for apple orchards and wineries—and sometimes jokingly referred to as the Palm Springs of Washington—Yakima can also present a limited view of future possibility, with pockets of gang violence, gunshots that interrupted football practices, a median household income of $44,950 and a poverty rate that has climbed over 20% in recent years. Add in Yakima’s remote location relative to major cities, and it’s rare for anyone to see a future as bountiful as Kupp did.

He can thank his paternal grandfather for that.

Jake Kupp grew up on a farm. With money tight, his mother insisted that he read, because she wanted Jake to visualize far-away worlds and transport to them, hoping to broaden his outlook beyond, Jake says, “what my ‘normal’ capacity would be.”

On hot summer days, when the harvesting concluded, he settled under a peach tree. Lying down and looking up, he visualized an impossible future: playing baseball for the Yankees. He would manifest those visions, transform his body and transcend the limits of his circumstances. He did become a professional athlete, although in football, where he played 12 seasons for four franchises, earning a Pro Bowl nod while with New Orleans.

Jake returned to Yakima and passed the dream gene to his son, Craig, who carved out his own NFL career, as a backup quarterback with three NFL teams and for two World League franchises. Both created an incubator for young Cooper, while he crashed into the now-dented fence in the backyard of his family home or sidestepped the sandbox into an end zone marked off by a garden hose stretched across the grass. Jake read him The Little Engine That Could. Craig told Cooper he could do anything he wanted.

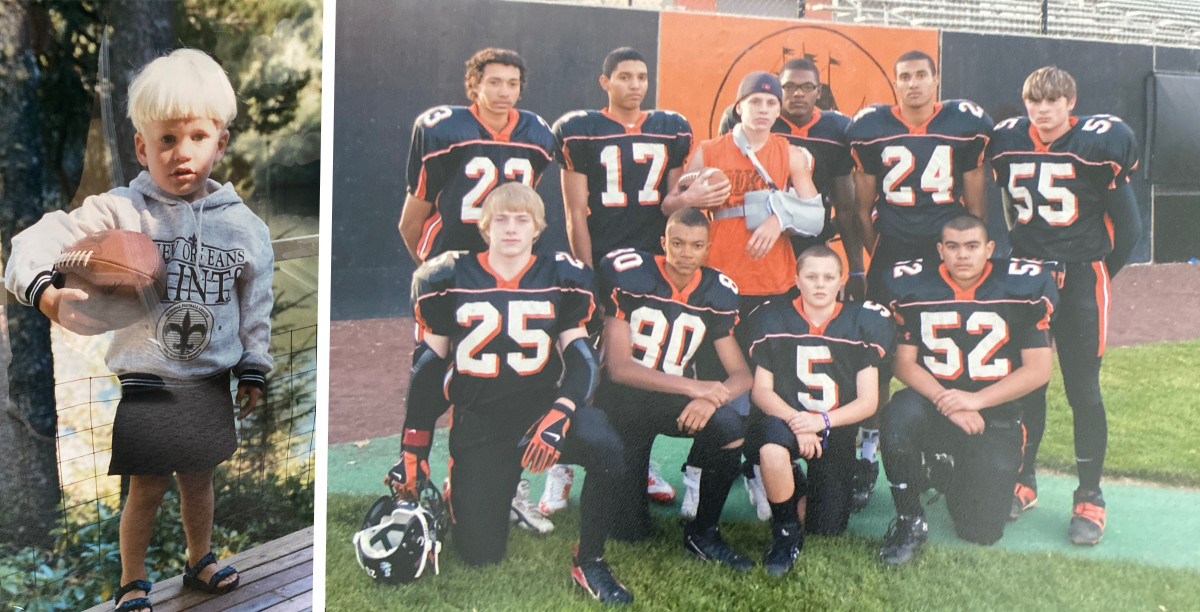

Young Cooper Kupp, wearing the sling on the right.

Courtesy of the Kupp Family

For a future football scientist obsessed with objective data, Cooper could have looked at his size (way under 150 pounds entering high school) and his prospects (no Division I scholarship offers) and the small number of white NFL receivers and come to an obvious conclusion: He held, at best, infinitesimal odds. Instead, his family taught him to see beyond.

Cooper’s aspirations grew in lockstep with his body. He watched film of legends: Rice, Irvin, Johnson, Marvin Harrison, Randy Moss. But rather than see what he could never be, he dreamed of something else: his future.

One morning before his sophomore football season, Cooper cornered his coach, Jay Dumas, in the weight room that doubled as his peach tree. Did Dumas think he could play in college? Yes. Maybe. Could. “In the back of my mind, I thought he’d probably play at Central Washington,” Dumas says, referring to the nearby Division II program.

Cooper asked: What about the NFL? Dumas stifled his laughter, laid out percentages that screamed no and kept his true thoughts—that’s not realistic—to himself. But Cooper wasn’t done. He confessed to another goal, his loftiest. He wanted to enter the … Pro Football Hall of Fame. Dumas waited for the punch line that never came. Even if Cooper achieved his “normal” capacity, his “do anything” landed in outer space. Let him dream, Dumas decided.

Karin Kupp ran marathons, taught fitness boot camps and competed in extreme endurance races. There’s a picture of her in the family basement hurtling through actual flames. Cooper sometimes tagged along and, in his teens, he completed a mini-triathlon alongside her. His parents snapped a picture: Cooper lying on the ground afterward, exhausted, unable to move. They alternately loved and worried about his determination. They wanted Cooper to harness what drove him, to find a proper equilibrium, a notion made prominent by the ulcer he developed in sixth grade. With little else to explain the diagnosis, they wondered whether Cooper cared too much, whether what fueled his plan had flooded his digestive tract with acid.

Cooper never stopped pushing, and not in the cliché sense, like a bad answer to the what’s-your-greatest-weakness job interview question. His pushing-pushing-pushing could add risk he might have otherwise avoided. Cooper played basketball to develop agility and yet inevitably ended up near the basket, elbows flying, taking on opponents who doubled his size. Yes, he tipped in a shot that kept alive the season when Davis High won the state championship. But that same fearlessness led to a broken collarbone on the football field, stoking concerns over a dogged approach that was admirable and questionable. Admirable because nobody worked harder, looked deeper, tried more approaches. Questionable because no matter how hard he pushed, his odds would remain low, his dream just that. Cooper had to weigh a risk-reward calculus, had to answer: At what cost?

Did he really need to wear ankle weights all day long? Did he absolutely have to befriend the school’s custodian so he could access the weight room at all hours, dumbbells clanking each morning before sunrise?

Cooper uncover

Last edited: